By Mark Hemingway

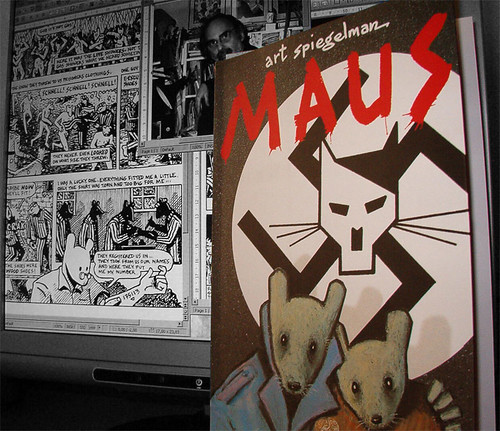

On January 26, Judd Legum, a liberal activist who runs a very large newsletter called Popular Information, reported that the school board in McMinn County, Tenn., had voted to “ban” the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel “Maus.” The book has been hailed as a classic of literature about the Holocaust. It also contains several graphic passages. Before the end of the day, news of the ruling of a school board in a small rural county had spread like wildfire across the Internet. It even warranted a breaking news alert at the New York Times.

Unfortunately, much of the coverage of this story – and many others like it as school curricula have become a hot button political issue – has been disingenuous. I don’t take concerns about book banning lightly. In my more than two decades as a journalist, it’s not an exaggeration to say I’ve written hundreds of thousands of words arguing for a robust and expansive definition of free speech. I have publicly defended French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo’s right to blaspheme in the face of terror attacks, just as I have deplored cancel culture and campus speech codes.

However, I’ve also spent more than a decade on the board of a private school, and decisions about what’s taught in K-12 classrooms and what ends up on school library shelves isn’t a tidy free speech issue. When the national media suggest that parents, administrators, and teachers are censors – or, worse, are “banning” books – by making necessary decisions about what reading material is age-appropriate or meets community standards, more often than not these news outlets are the ones politicizing education.

In the case of McMinn County, the 10-member board didn’t vote to ban “Maus” – but it did remove it from the school’s eighth-grade curricula because it felt the book’s profanity and graphic depictions of violence and suicide were too much for 13-year-olds. “Maus” is still in print, taught in many schools elsewhere, and widely available even in McMinn County. The McMinn school board members went so far as to state that they felt it important to teach students about the Holocaust, and even said the district might go back to teaching “Maus” if something else more suitable on the topic can’t be found.

The national media, however, seems to feel concerns about nudity and profanity in “Maus” belie a more sinister agenda. The New York Times made a scurrilous implication, asserting that McMinn County’s “decision comes as the Anti-Defamation League and others have warned of a recent rise in antisemitic incidents.”

A similar controversy erupted in Virginia in the midst of last year’s closely watched gubernatorial election, when Republican Glenn Youngkin released an ad arguing for more parental input in schools. The ad featured a woman who had previously campaigned to remove “Beloved,” Nobel Prize-winning author Toni Morrison’s book, from her son’s school; again, this was presented as proof that Youngkin’s real agenda was censorship.

“Beloved” is undoubtedly a worthy piece of literature, but again, it is an extremely graphic book about a woman who kills her own child to escape the horrors of chattel slavery, and it includes descriptions of explicit sex and bestiality. The Virginia parent who campaigned against it said that it gave her child nightmares. Having doubts about the book being taught in high school is hardly a “war on library books,” as Legum has characterized it.

Youngkin’s victory in a Democratic bastion that hadn’t elected a Republican statewide in over a decade showed the potency of campaigning for the rights of parents in education. The losing candidate, Terry McAuliffe, had vowed not to “let parents come into schools and actually take books out and make their own decisions.”

But if there’s no war on library books, parents have reason to be concerned that librarians don’t always have kids’ best interests in mind. Some years ago, an administrator at the school where I serve on the board told me they had confiscated a book from a student. I asked to see it. It was one of the “Pretty Little Liars” novels, which spawned a show that aired on the now-defunct ABC Family Channel. I’d venture that most parents would think this means it’s probably a safe choice for adolescents and teenagers. However, the administrator showed me a scene of two teenage girls engaging in sexual behavior with each other amid bargain basement prose calculated to titillate. I agreed the book should not be allowed at the school.

Every year during “Banned Books Week,” the American Library Association regularly undermines its own cause by championing the right of school libraries to stock lurid kids’ books such as “Pretty Little Liars” and the similar “Gossip Girl” series – and to smear parents and educators who express qualms about them. The implication is that objecting to exploitative doses of explicit sex and drug use currently found in the young adult fiction market is one step removed from throwing “To Kill a Mockingbird” on the bonfire.

It’s obvious that many of those criticizing the McMinn school board have no problem with “book banning” when it suits their particular values. Last year, Dr. Seuss Enterprises, the company in charge of works by the beloved author of children’s books, decided to stop printing six of Seuss’ stories over racially insensitive drawings. Liberal America vociferously defended the decision as a matter of political correctness – even though the decision to stop printing the books, along with eBay’s decision to forbid the sale of used copies of them, was akin to actual book banning (as opposed to merely removing the offensive books from school shelves).

The politicization of school curricula has given liberals legitimate cause for concern – some local conservative activists have drawn up extensive lists of books they think should be removed from schools. And there’s been a raft of state and local legislation aimed at banning critical race theory from school curricula that critics worry is overly broad and could be used to needlessly limit what is taught.

These developments bear real scrutiny, but the media’s reflexive partisanship only confirms the fears of conservative parents. Notice how NBC News is choosing to frame the coverage over new legislative proposals for transparency in schools: “Conservative activists want schools to post lesson plans online, but free speech advocates warn such policies could lead to more censorship in K-12 schools.”

Similarly, complaints about “book banning” in McMinn County come off as a barely concealed attempt to shame people in rural America for what should be perfectly tolerable differences in regional and cultural values. This only validates the concerns of Americans worried about powerful forces undermining local control of education to serve a national political agenda.

“When conservatives want to talk about liberal excesses, they talk about Yale, big tech, the NYT, the federal bureaucracy, the Ford Foundation, medical associations, etc.,” notes Richard Hanania of the Center for the Study of Partisanship and Ideology. “When liberals want to talk [about] conservative excesses, they talk about the ‘McMinn County School Board.’”