Henry Clay’s “American System” was bad news for the American economy, every time it was tried, says economic historian Phil Magness.

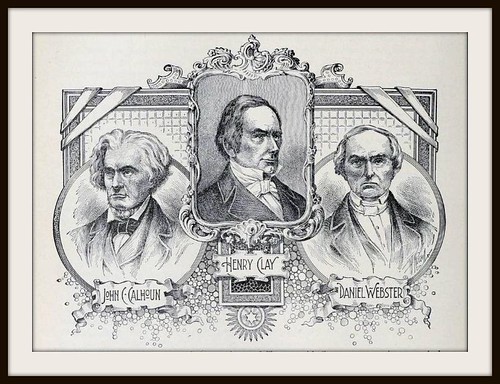

Some ideas are so bad we are doomed to relive them with each successive generation. Until recently, economic central planning from the political right received far less attention than its well-known manifestations on the left. Think of all the repeated attempts to rehabilitate Marxism and socialism, despite their disastrous track record over the last century. Unfortunately, an emerging faction on the political right has decided to deploy economic planning of their own as an intended countermeasure against their progressive foes. For inspiration, they’ve resurrected a failed and long-forgotten idea from the 19th century: Henry Clay’s “American System.”

Clay’s program was first articulated in an 1824 speech, in which he proposed using the Constitution’s tax and regulatory powers to execute America’s first national foray into centralized economic planning. His basic idea was to enlist the might of the federal government to strategically develop certain sectors of the American economy by subsidizing them with tax dollars, and penalizing their foreign competitors with high protective tariffs.

Clay maintained that import tariffs could be used to give American manufacturers a leg up over European goods, while also cultivating “infant industries” that he deemed to be in the young nation’s strategic interests. Topping off the package, Clay proposed a spending spree on federally subsidized “internal improvements,” such as roads and canals to facilitate internal commerce, and a strong central bank to facilitate the financing of large government programs through the issuance of sovereign debt. In total, the program amounted to a comprehensive attempt at economic planning around the mistaken belief that trade is a zero-sum game, and countries were locked in a continuous struggle to maximize their industrial outputs by subsidizing themselves and taxing their perceived foreign competitors.

If all of this sounds vaguely familiar, it should. It’s part of the protectionist-tariff playbook we witnessed during the Trump presidency. Or maybe it’s better seen, as William Galston asserts, as representing “an effort to bring some ideological coherence to the impulses Donald Trump represents—nationalism, isolationism, social conservatism, and hostility to immigration.”

Indeed, Robert Lighthizer, the former Trump cabinet official who was responsible for international trade policy, recently called for the adoption of a “New American System” based on Clay’s 1824 proposal in a speech in Washington, D.C. Henry Clay’s scheme similarly assumed center stage at the recent National Conservatism Conference in Miami, Florida, when historian Michael Lind depicted him as the true successor to the American founding, by way of Alexander Hamilton.

Clay’s ideas have also found an institutional home at the American Compass, a think tank set up by Oren Cass, Mitt Romney’s former economic advisor. It would be difficult to overstate the rapid pace at which Clay’s ideas have surged out of obscurity and into political discussions on the right. Barely two decades ago, discussions of it were almost entirely relegated to the peripheral fringes of American politics. Today, Florida Senator Marco Rubio invokes Clay as a model for constructing a US industrial policy to counter the economic rise of China.

The fundamental problem with this line of reasoning is that it rests on bad economic history, overlaid with the logical fallacy post hoc ergo propter hoc.

The “new American System” advocates tell a version of US economic history that goes something like this. In the early 19th century, the United States entered the world scene as an economic backwater facing insurmountable competition from the established industrial nations of Europe, and particularly Great Britain.

By the turn of the twentieth century, the United States had emerged as one of the world’s great industrial powers, even surpassing the Old World despite getting a later start. The credit for this growth, they claim, goes to the “American System” policies that Clay championed: high protective tariffs, subsidized “internal improvements,” the gradual expansion of a powerful central bank, and all around economic planning.

Even the basic claims of this story are in error. As economist Douglas Irwin has shown, proponents of the theory that tariffs drove American economic growth “have tended to present statistics that overstate late nineteenth century US growth in comparison to other periods and countries.” After examining the empirical evidence, Irwin concludes, “It is difficult to attribute much of a positive role for the tariff because import tariffs probably raised the price of imported capital goods, thereby discouraging capital accumulation.” He accordingly rules out the theory that trade protection, the main plank of Clay’s platform, caused the United States to become a world economic power.

But there are even-more-fundamental problems with the new “American System” theorists’ history. They get basic facts wrong about the nature of 19th century economic policy, while simultaneously obscuring or ignoring the many downsides of Clay’s program and its attempted implementation.

The Rise and Demise of the American System

Though once a popular political slogan, Clay’s American System fell into disrepute after a series of discrediting blows in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The first came in 1832, when President Andrew Jackson vetoed legislation to recharter the United States’ corruption-plagued central bank. The creation of the Federal Reserve in 1913 resuscitated this legacy, along with its tendency to engage in political manipulation of monetary policy, though the Bank War did manage to constrain the push for centralization on that front for much of the 19th century.

Clay’s original tariff program endured a bit longer, finding legislative support at various points between 1824 and 1930. As the chart below shows, however, the 19th century was not an uninterrupted experiment in Clay-style protectionism. Clay only briefly got his way when a series of tariff measures between 1824 and 1828 jacked the average rate on dutiable goods to over 60 percent. The “Tariff of Abominations,” as the 1828 measure came to be known, sparked a political crisis that brought the country to the brink of disunion, after South Carolina attempted to nullify the high tax measure.

As the graph shows, from 1833 until the Civil War, the United States charted a course of tariff liberalization, save for a brief interruption when Clay’s Whig Party attained power in 1842. In fact, in 1846 US Treasury Secretary Robert Walker orchestrated a major tariff liberalization to coincide with Great Britain’s famous repeal of the protectionist Corn Laws that same year.

The United States did not reimpose high tariffs in the Clay model with any degree of permanence until the second half of the nineteenth century. While this period did coincide with economic growth, the claim of a causal relationship ignores the fact that the American economic ascendance was already well underway, preceding those tariffs by several decades, and getting its start in a time of relative trade liberalization on both sides of the Atlantic.

One of the main reasons Henry Clay struggled to get his American System launched in his own lifetime (1777-1852) was the political corruption it always attracted. In practice, the American System’s rationalization of trade protectionism provided cover for rampant graft and favoritism. From the moment of its inception, politically connected special interests seized control of federal tariff legislation and reshaped it to their own benefit. They lobbied for punitive tax rates on their competitors and pork-laden handouts for themselves, even if it meant overtaxing commerce at the expense of revenue itself.

At several points in the 19th century, protectionist tariffs pushed the US tax system into the upper half of the Laffer Curve, where rates became so onerous that they undermined the intake of federal tax revenue. This was by design, as protectionist tariffs use taxes as a weapon to deter foreign goods from even entering the country.

The American System and Slavery

Clay’s American System also struggled to disentangle its doctrines from the institution of slavery. Its underlying theory held that the American economy could be “harmonized” and internally integrated through national economic planning. That meant deploying “internal improvements” and the tariff schedule to bind northern industry and southern agriculture together in economic symbiosis.

Clay’s doctrines amounted to an early experiment in import substitution: the strategy of using tariffs and other commercial restrictions to divert raw-material production away from international markets and into a heavily subsidized domestic industry. In practice, this meant intentionally shifting southern cotton production away from transatlantic markets and into the textile mills of New England. In order for the American System to function as intended, it would have to subsidize plantation agriculture as well as northern industry.

Some of the American System’s proponents, including Clay himself, eventually recognized that a full “harmonization” of the US economy under the American System would entail significant public expenditures to develop southern agriculture, thereby politically entrenching slavery in perpetuity. Clay (who, despite being a slave-owner, had reservations about the institution) therefore devised what is often referred to as the “Whig formula” for addressing slavery through a scheme of federally compensated gradual emancipation.

To facilitate this program, Clay appended the American System doctrine with another plank. In addition to paying for “internal improvements,” federal land sale revenue would be allocated to “colonize” or resettle the African-American population of the United States in faraway tropical locations such as Liberia or Central America. As Clay explained in an 1847 speech, federally subsidized colonization “obviated one of the greatest objections which was made to gradual emancipation,” that being the “continuance of the emancipated slaves among us.” Following Clay, American System theorists such as economists Mathew Carey and his son Henry C. Carey began to champion the black colonization movement as a “solution” to the problems that slavery presented to their tariff and subsidy scheme. In order to make the system work without plantation slavery, they would simply export the freed slaves abroad.

Aside from a few experiments such as the founding of Liberia, such schemes proved impractical, and eventually succumbed to political obstacles during the American Civil War. Clay’s tariff system nonetheless gained a foothold on the eve of the war, as protectionist interests exploited the chaotic “secession winter” legislative session of 1860-61 to cram the pork-laden Morrill Tariff Act through Congress.

A Civil War Diplomatic Disaster

Although the Morrill Tariff succeeded in finally installing an American-System-style tariff regime for the next half-century, it quickly turned into a diplomatic disaster. The new law’s steep protectionist rates alienated the British government, which would otherwise have been a natural anti-slavery ally to the Union cause. At the outbreak of the war, British abolitionist and free-trader Richard Cobden wrote his friend Charles Sumner, the US Senator from Massachusetts, to plead the importance of free trade to the anti-slavery cause. “In your case we observe a mighty quarrel: on one side protectionists, on the other slave-owners.” Citing the Morrill Tariff supporters’ publicly expressed reluctance to move against slavery, Cobden predicted the measure would imperil his efforts to steer Britain to the aid of the North. As he rhetorically asked his fellow abolitionist Sumner, “Need you wonder at the confusion in John Bull’s poor head?”

As part of the fallout, the Lincoln administration entered the White House facing an irate diplomatic landscape. In part alienated by the tariff, Britain adopted a stance of neutrality toward the two American belligerents. After successive missteps further soured the Lincoln Administration’s relationship with London, abolitionists such as Cobden had to mobilize opinion on the British homefront against the Confederacy by reminding people of slavery’s central role in the war.

The diplomatic row, which began with an ill-conceived and opportunistic tariff bill on the eve of Lincoln’s inauguration, would plague US-UK relations for decades to come. Its wartime effect thrust the incoming administration into a needlessly hostile diplomatic situation, handicapping the Union’s war efforts from abroad.

As a domestic economic policy, the Morrill Tariff served a slew of special interests in the northeast by placing punitive taxes on their competitors. It did not finance the Union war effort (as is often incorrectly claimed by American System enthusiasts) as it was never intended for the purpose of raising revenue. The Morrill Tariff primarily aimed to deter commerce from abroad at the behest of domestic manufacturing, allowing them to capture increased prices on their own goods. As a war measure, it amounted to a self-inflicted wound by alienating Britain from the Union’s cause.

How Clay’s Tariffs Gave Us the Income Tax

After the Civil War, the tariff issue came to dominate American economic policy. Until 1909, the successors to Clay’s “American System” generally enjoyed the upper hand. That year, President William Howard Taft called for a routine revision to the federal tariff schedule that quickly devolved into a corrupt free-for-all of tariff favoritism and special-interest handouts.

Amidst the backlash against the Payne-Aldrich Tariff Act’s special-interest free-for-all, a coalition of free trade Democrats and breakaway Republican “insurgents” in the US Senate turned to a radical solution. Realizing that they would never break the monied interests of the protectionist lobby, they proposed restructuring the entire federal tax system by shifting it away from the corruption-prone tariff schedule. The result was the 16th Amendment, a flanking move that tried to substitute the protective tariff system with the federal income tax. The amendment, one legislator boasted at the time, would serve as a “club to beat down the tariff” by separating the federal tax system from the entrenched protectionist lobby.

For a fleeting moment, the strategy worked. In 1913, Congress cut import tariffs to their lowest point since the 1850s, and imposed a modest income tax to make up for the loss of revenue. The special-interest groups quickly reconstituted though, and in 1922 they succeeded in exploiting an economic downturn in the agriculture sector to make the case for renewed protectionism.

Since the income tax already provided the lion’s share of tax revenue, lawmakers no longer had to worry themselves about jacking up tariff rates to prohibitive levels. As a result of this post-World War I resurrection of Clay’s “American System,” the United States ended up with the worst of both worlds: high tariffs to raise the prices on imported goods at the behest of their domestic competitors, and a new federal income tax to extract revenue from them at every opportunity.

When Americans complete their income tax filings today, few realize that the interminable frustrations of this annual ritual have their origins in a now-obscure tariff bill. It was the corrupt overreach of Clay’s “American System,” though, that ultimately bequeathed us with the modern IRS.

Smoot-Hawley and the Collapse of Clay’s Doctrine

The legislative progeny of Henry Clay’s doctrines finally came to a catastrophic head in 1930 when Congress enacted the Smoot-Hawley Tariff. The measure passed in a desperate attempt to shield special interests from the 1929 stock market crash, although its legislative origin predated “Black Monday” – October 28, 1929 – by several months.

The congressional record shows that Smoot-Hawley took its direct inspiration from Clay’s doctrines. The debate on the bill commenced in the House of Representatives earlier that May. Making the case for the protectionist side, Rep. Hamilton Fish (R-NY) declared that “the Republican Party has just one viewpoint, and that is to protect American labor and American industry, not through a competitive tariff but through a tariff that actually protects.”

To reinforce his point, Fish quoted “a brief extract from a speech of Henry Clay in favor of a protective tariff…which has never been improved on and has constituted the Republican tariff doctrine for the past 70 years.” After quoting Clay’s American System speech from 1824, Fish offered his rationale for adopting a renewed protectionist policy in 1929. It reads like a talking point from Oren Cass’s American Compass today:

“The prosperity of this Nation has been built up because the Republican Party has hewed to the line to protect American labor and American industry and to conserve the home markets from ruinous competition with the low-paid labor in foreign countries.;”

In a prescient response, another representative challenged Fish by warning that a tariff hike could lead to economic turmoil, including triggering a harmful turn in already-uneasy unemployment numbers. If the tariff passed, was Fish ready to take “credit for the general condition of unemployment that now exists in the United States?” After dissembling over particular, contested tariff rates and the need to serve a multitude of special interest constituencies, Fish reiterated the philosophical justification for pushing ahead. He again invoked Henry Clay’s American System:

“That principle was laid down by Henry Clay-the principle of protecting the home market. It is just the reverse of the English attitude. They export 90 percent and only absorb 10 percent of their products in their own home market: We consume in this country 90 percent of our home product and export 10 percent. The question is simply whether you prefer to conserve the home market and protect American wage earners or let the products of low-paid foreign labor destroy the home market for the American producer.”

The stock market crash in October poured gasoline onto an already-burning fire as the Smoot-Hawley bill progressed through Congress. The pork-barrel free-for-all saw money changing hands between lobbyists and legislators on the floor of the committee rooms, as industry after industry attempted to purchase “protection” for itself from the unfolding economic recession.

They thought they were weathering the storm by obtaining legislative favors. Instead, the cumulative hikes of Smoot-Hawley boosted tariff rates to a historic high of almost 60 percent on all dutiable goods entering the United States. The measure provoked a wave of retaliatory protectionism across the world. In just four short years, Smoot-Hawley had inadvertently triggered a global collapse in international commerce.

The effects may be seen in the famous “spiral” graph published by the League of Nations’ World Economic Survey in 1933. By pursuing the course advised under the “American System” doctrine, the United States directly helped to put the “Great” in “Great Depression.”

Repeating Old Mistakes

The National Conservative argument for the “American System” correctly observes that there were moments in United States history when the country largely adhered to Henry Clay’s suite of high protectionist tariffs, public works projects, and allegedly strategic industrial subsidies. They also choose to deemphasize, or may even remain ignorant of, the American System’s more ignominious legacies.

You will seldom encounter, for example, a NatCon who seriously engages with the moral conundrum that slavery created for Clay’s import-substitution scheme before the Civil War. The American System’s colonization plank is almost entirely absent from these discussions, and its propensity for attracting graft and corruption in its later iterations is almost always swept under the rug.

Instead, the version they present is an idealized form of seamlessly executed economic planning, albeit for “strategic” purposes in the “national interest” instead of the left’s usual litany of social justice causes. The inherent coordination problems of centralized economic planning do not simply melt away when it is directed at nationalist objectives instead of progressive, redistributive goals.

But there’s an even-more-fundamental problem with the American System narrative. Its modern rehabilitators conveniently leave out the fact that every time it was tried in the 19th and early 20th centuries, Clay’s program unleashed a torrent of preventable policy disasters.

In 1828, a protective tariff pushed the country to the brink of disunion while also demonstrating Clay’s own inability to extricate his program from the slave economy.

In 1861, Clay’s economic philosophy triggered a diplomatic crisis with Britain that unwittingly alienated an anti-slavery ally from the Union cause.

In 1909, the heirs of Clay’s economics became so thoroughly beholden to the corrupt dealings of the tariff lobby that a section of their own party revolted and ushered in the haphazardly designed federal income tax system that plagues us to this day.

And in 1930, Clay’s political progeny steered the country directly into economic ruin by embracing an American-System-inspired tariff program as its main countermeasure to the unfolding Great Depression.

While Clay’s latter-day advocates jump at every opportunity to credit him for late-19th-century American economic growth despite a weak empirical basis for the claim, they also conveniently omit the track record of real and tangible blunders that followed from a century of experiments in American System economic policy.

In the case of the Clay-inspired Smoot-Hawley Tariff, the resulting collapse in international trade proved so disastrous that it largely expunged the American System’s advocates from both political parties in the post-war 20th century. Starting with the Reciprocal Trade Agreement Act in 1934, Congress embarked on a slow-but-steady retreat from protectionism that continued until the early 2000s.

The passage of time has, unfortunately, dampened our memory of Smoot-Hawley’s self-inflicted wounds, to say nothing of Clay’s 19th-century failings. Now the National Conservatives deceive themselves into believing that they have rediscovered hidden knowledge from our economic past: knowledge that will allow them to beat the central planners of the left by putting their own spin on central planning from the right. In reality, they risk haplessly stumbling into the same mistakes that discredited Clay’s American System in the eyes of the last generation to experience its results.

America’s progressive left have always, either tacitly or by expression, bought into the impulses of economic planning. The shocking thing happening now is that we have conservative participation in the American System too, and why wouldn’t we? Tariffs are a dyed in the wool winner for anyone who wants to push them onto the American people. Those people never seem all that interested in getting past the emotive costume of tariffs. “Let the other guy, the foreigner, pay the bill for a change.” That tariffs are coming back around to steal all kinds of American wealth never quite makes the evening news.

So elements of the right have jumped onto this centrally planned economic train. And why wouldn’t they? There are illusions of easy political wins to be had. And that’s all you really need to know.

Originally published by the American Institute for Economic Research. Republished with permission under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

For more great content from Budget & Tax News.