By Bonner Cohen

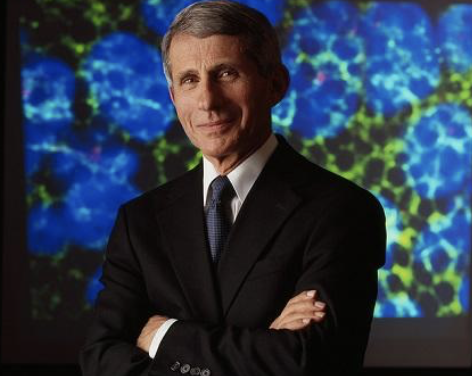

No public-health official has come to embody the United States’ response to COVID-19 more than Dr. Anthony “Tony” Fauci, director of the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). The 79-year-old physician and immunologist, who has headed NIAID since 1984, has overseen the policies adopted to keep the virus in check and has been the Trump administration’s public face on COVID-19.

Fauci’s public pronouncements have often been contradictory or vague and have sown confusion, however, even as the disease has shown itself to be more resilient if less deadly than many experts originally projected.

Mask and Mirrors

The now-ubiquitous facemask serves two functions, according to the American Council on Science and Health: “protecting the wearer by limiting the inhalation of airborne particles and protecting others by reducing the transmission of virus particles exhaled by an infected individual.”

As the COVID-19 outbreak arose in late February and early March, Fauci and U.S. Surgeon General Jerome Adams advised against wearing masks. Fauci later reversed himself, explaining his about-face in an interview with CBS News in July.

“I don’t regret anything I said then because, in the context of the time in which I said it, it was correct,” said Fauci. “We were told in our task force meetings that we have a serious problem with the lack of PPEs [personal protection equipment] and masks for the health providers who put themselves in harm’s way every day to take care of sick people. When it became clear that the infection could be spread by asymptomatic carriers who don’t know they’re infected, that made it very clear that we had to strongly recommend masks.”

Social Distance Dance

Like masks, social distancing is seen as a way to reduce the transmission of virus particles. On March 6, Fauci told NBC Seattle social distancing was the right strategy for the nation but “we’re not there yet.”

Asked by CNN on April 12 whether lives could have been spared if social distancing had been implemented several weeks earlier, Fauci said, “Again, it’s the ‘what would have, what could have.’ It’s very difficult to go back and say that.”

“I mean, obviously, you could logically say that if you had a process that was ongoing and you started mitigation earlier, you could have saved lives,” Fauci said. “Obviously, no one is going to deny that. But what goes into these kinds of decisions is complicated.”

Whatever his views on social distancing were at the onset of the pandemic, by late June Fauci was a staunch advocate of the practice.

“Whatever you congregate for and you don’t pay attention to physical distancing, you’re increasing the risk of infection,” Fauci told Vice’s Shane Smith on the outlet’s “Shelter in Place” series.

Lockdown Lamentations

No measure to combat the spread of COVID-19 has been more controversial than the massive lockdowns imposed last spring by most governors and many local officials.

The self-inflicted economic collapse resulting from the lockdowns threw millions of Americans out of work and destroyed hundreds of thousands of businesses. In addition to the economic devastation, the lockdowns have had dire public-health consequences, as noted in the Great Barrington Declaration (see article, page 20).

Organized by three infectious-disease experts at Harvard, Oxford, and Stanford Universities, the declaration, which has collected thousands of signatures from medical and health scientists, says the damage from government lockdowns “include[s] lower childhood vaccination rates, worsening cardiovascular disease outcomes, fewer cancer screenings, and deteriorating mental health—leading to greater excess mortality in years to come, with the working class and younger members of society carrying the heaviest burden.”

In late June, Fauci acknowledged the tradeoff between the economic hardship of lockdowns and the fight against COVID-19.

“It’s the free spirit of people in the United States, who understandably felt so cooped up for so long, jobs were lost, the economy went down, so that was almost an all-or-none revolution saying either we’re going from shutdown to all bets are off,” Fauci said.

Transmission Transition

With its January 14 tweet that there was “no clear evidence” the coronavirus could be spread between humans, the World Health Organization (WHO) opened itself up to a barrage of criticism that only escalated as the pandemic spread.

While avoiding such a blanket declaration, Fauci sent mixed messages. Asked by syndicated radio host John Catsimatidis on January 26 whether Americans should be “scared,” Fauci responded, “I don’t think so. The American people should not be worried or frightened by this. It’s a very, very low risk to the United States, but it’s something that we, as public health officials, need to take very seriously.”

Five days later, President Donald Trump imposed travel restrictions on people entering the United States from China, where the coronavirus originated.

Vaccine Vacillation

Ever since the seriousness of the pandemic became clear, drug companies have been scrambling to produce a vaccine against COVID-19. The big question has been how long it will take before people will have access to an effective vaccine.

The matter is complicated by the U.S. Food & Drug Administration’s notoriously slow approval process and the fact several competing vaccines are in various stages of testing. Fauci may have added to the uncertainty by his own statements.

In September, Fauci told the Journal of the American Medical Association vaccinations could begin as early as November or December of this year. But he then added, “By the time you get enough people vaccinated so that you feel you’ve had an impact enough on the outbreak so that you can start thinking about maybe getting a little bit more towards normality, that very likely, as I and others have said, will be maybe the third quarter of 2021. Maybe even into the fourth quarter.”

Bonner R. Cohen, Ph.D., (bcohen@nationalcenter.org) is a senior fellow at the National Center for Public Policy Research.

(photo courtesy, NIAID)