The COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns continue to impact lives all over the world—developing countries have been especially hard hit with increasing poverty and famine, preventable diseases, and long-term economic downturns.

Reports published this fall show that the lockdowns have put millions of people into extreme poverty, the first increase in 20 years. The World Bank stated on October 7 that as many as 150 million people, about nine percent of the world’s population, could be living on less than $1.90 a day. On September 18, 2020, United Nations (UN) officials warned acute food insecurity is expected to double this year, from 135 million people to 270 million people.

With respect to preventable diseases, a London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine study suggests that for every COVID-19 death prevented, 84 children may die from a lack of routine vaccination. Additionally, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) predicted in May 2020 that an additional 6,000 children could die every day from preventable causes over the following six months. This increase in additional child deaths would be felt the most in countries with weak health systems and medical supply chains, including Bangladesh, Brazil, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia, Nigeria, Pakistan, Uganda, and the United Republic of Tanzania.

The reports are not surprising, says Jane Orient, M.D., executive director of the Association of American Physicians and Surgeons and a policy advisor to The Heartland Institute which co-publishes Health Care News.

“Economic shutdowns are disastrous,” Orient said.

Lockdowns Kill Both People and Economies

In early October, the World Health Organization (WHO) appealed to world leaders to stop using lockdowns as the primary control method for COVID-19.

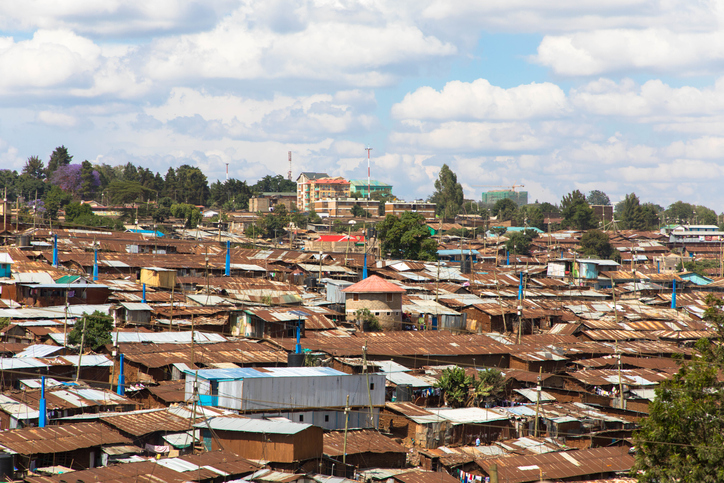

Specifically, Dr. David Nabarro, the WHO’s Special Envoy on COVID-19, said that lockdowns predominately devastate poor economies and “make poor people an awful lot poorer.” It would also impact access to proper sanitation, clean water, food, and other resources, Nabarro said.

“Look what’s happened to smallholder farmers all over the world,” Nabarro said. “Look what’s happening to poverty levels. It seems that we may well have a doubling of world poverty by next year. We may well have at least a doubling of child malnutrition.”

The WHO should know that lockdowns would disproportionately impact poor people and nations, says Michelle Cretella, M.D., executive director of the American College of Pediatricians.

“It is not surprising the loss of life and economic devastation lockdowns have wrought in developed countries has had negative ramifications in the third world,” Cretella said. “The WHO could have predicted all of this but chose politics over science and human life.”

Future Generations Set Back

Lockdowns impacted children around the world with respect to more than preventable diseases and nutrition: many have not returned to school.

In August, UNICEF reported that more than 90 percent of countries have implemented some form of remote learning. It also estimates that at least 463 million students, a third of the world’s schoolchildren, remain cut off from education, with students in rural areas the hardest hit. The highest percentage of students that are cut-off from learning is in Eastern and Southern Africa, with 49 percent of students who cannot be reached.

Even if those students could be contacted, remote learning is not a substitute for in-person school. Children who are participating in remote school may not be learning, especially in situations where parents cannot be there to help their children during school hours, Orient says.

“I don’t know that ‘remote learning’ works anywhere,” Orient said. “They need books, not a blue screen, pencil and paper, not a mouse, and someone to keep them on task. Those things can be present in a poor rural home or absent in the most affluent one.”

Letting children suffer from lockdowns is even more difficult to understand, Cretella says.

“Experts agree that the vast majority of children have only mild symptoms and recover very quickly from COVID-19,” Cretella said. “Children are also not super-spreaders, meaning there is good evidence from around the world that children should be learning in schools in person—period.”

If closing schools has been prompted by concerns over protecting adults, there might be other solutions, Cretella says.

“We must take a non-politicized look at hydroxychloroquine (HCQ),” Cretella said.

HCQ is an anti-viral drug that has been on the market for decades. A meta-analysis shows that if used early during the onset of COVID-19 and in low doses, HCQ can reduce death and hospitalization by at least 24 percent.

The effects from lockdowns may loom a long time for many poor people and countries, Orient says.

“It could be the destruction of the middle class and small business,” Orient said. “Who will take the risk of starting a business if the government can arbitrarily destroy it? We will be dependent on huge corporations with friends in high places.”

Kelsey Hackem, J.D. (khackem@gmail.com) writes from Washington State.

Internet info:

Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2020: Reversals of Fortune, The World Bank, October 7, 2020: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2020/10/07/covid-19-to-add-as-many-as-150-million-extreme-poor-by-2021

COVID-19: Are children able to continue learning during school closures?, UNICEF, August 2020: https://data.unicef.org/resources/remote-learning-reachability-factsheet/