The U.S. Senate committee dealing with health policy will be chaired by a Democrat who shares two major goals with the ranking Republican member. Both believe we should have universal health care coverage, and both believe it can be done with money already in the system.

Yet their views on how the health care system should function are so profoundly different there is hardly any overlap.

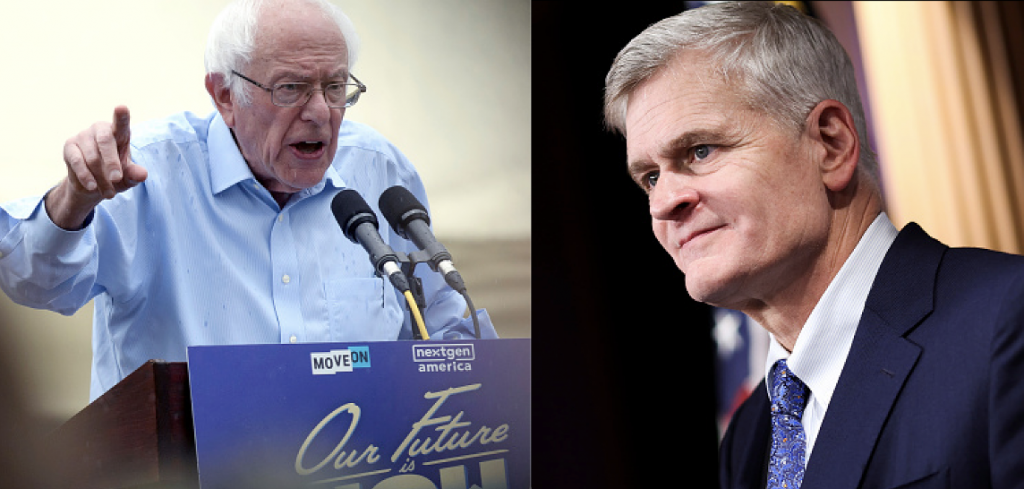

Bernie Sanders (D-VT) is slated to become chair of the Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions (HELP), and Bill Cassidy (R-LA) is expected to be the ranking member. Sanders will need help from Cassidy if anything is to be done in a closely divided U.S. Senate.

Because Sanders and Cassidy tend to have amiable natures, some observers are optimistically predicting a lot of bipartisan cooperation in the HELP committee over the next two years. But they overlook how differently the two think about health care.

Sanders’ Views

Most people are vaguely aware Sanders advocates Medicare for all. Yet what Sanders has in mind is very different from what the elderly and the disabled experience today.

For example, almost half of Medicare participants are enrolled in private Medicare Advantage plans, and traditional Medicare routinely contracts with for-profit hospitals and medical facilities.

If Sanders had his way, “profit” would be completely expunged from every aspect of the health care system. That means no doctor, no hospital, no insurer, and no participant of any sort would receive an economic reward for making health care less costly, more efficient, more accessible, and of higher quality.

Cassidy’s Views

By contrast, Cassidy has long believed most of our problems in health care exist because the United States, and most of the rest of the developed world, has succeeded in suppressing normal market forces.

As a result, none of us—patients, doctors, employers, and employees—ever sees a real price for anything.

Adam Smith taught us that in a well-functioning marketplace producers strive to meet the needs of their customers because it is in their economic self-interest to do so. The more needs they meet, the greater the economic reward they get.

Over the last 250 years, economists have produced an enormous body of research showing how well markets actually work. There has been surprisingly little research on how non-market systems function, however. Still, there are certain things we know.

If you suppress the price system and insulate providers from economic penalties and rewards, self-interest does not vanish. It is just redirected. One reason the British and Canadian health care systems perform so poorly is because it is not in anyone’s self-interest to make them work better.

Without Prices, Patients Wait

If you suppress the price system, you inevitably increase the importance of nonmarket factors—principally, rationing by waiting for appointments, tests, treatments, and surgeries.

In general, the lower the money price of care, the higher the time price will be.

In the United States, nonmarket barriers to care are apparently a greater obstacle to primary care than the fees doctors charge—even for low-income patients. This form of rationing is an even greater problem in Canada (where patients wait an average of 11 weeks to see a specialist) and in Britain (where 6.4 million people are on waiting lists for hospital care).

Several years ago, Sen. Cassidy introduced a bill with Rep. Pete Sessions (R-TX) that would have given every American a refundable tax credit for health care. Markets would be deregulated so that meeting people’s needs would be in everyone’s self-interest.

If you combine the average premium with the average deductible faced last year by people in the (Obamacare) exchanges, a family of four (not getting a subsidy) had to pay $25,000 before getting any benefit at all from their health plan. In contrast, the Cassidy bill would allow people to buy insurance meeting their financial and medical needs.

How Cassidy’s Bill Works

Instead of the Obamacare practice of forcing insurers to be all things to all enrollees, Cassidy’s bill would allow plans to become centers of excellence, specializing in such conditions as diabetes and heart disease.

Instead of the Obamacare requirement insurers receive the same premium for all enrollees, regardless of health condition, Cassidy would allow the kind of risk-adjusted premiums we see in the Medicare Advantage program. This is the foundation for a robust, competitive market for taking care of the sick.

Instead of the Obamacare practice of making health care even more bureaucratic than it was, Cassidy would liberate the market, allowing patients to compare prices. And we know when providers compete on price, they also compete on quality.

One way to think about all this is to see Sanders thinks incentives shouldn’t matter in health care. Cassidy accepts the fact incentives always matter—and that is why we need to get them right.

In Sen. Cassidy’s world, government would have two functions: (1) to make sure everyone has the financial means to enter the health care system and reap the benefits of market competition; and (2) to serve as a safety net, meeting any needs the private sector doesn’t.

Ironically, in Sen. Sanders’ world, there would be no safety net. If the Canadian government doesn’t provide a mammogram or hip replacement or heart surgery in a timely manner, it is illegal for the private sector to provide those services. In 2016, 63,459 Canadians traveled outside their country for medical care.

Clearly, for there to be a meeting of the minds on the HELP committee, there is a lot of ground to cover.

John C. Goodman (johngoodman@johngoodmaninstitute.org) is president of the Goodman Institute for Public Policy Research and co-publisher of Health Care News. An earlier version of this article appeared in Forbes on December 8, 2022. Reprinted with permission.

For more great content from Health Care News.