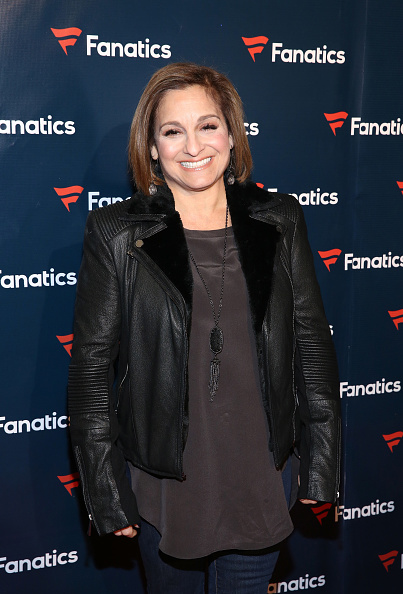

Gymnast Mary Lou Retton, one of the most charismatic Olympic gold medalists of all time, narrowly escaped death from a rare form of pneumonia last fall, only to be saddled with hospital bills she says she cannot afford to pay.

Retton, known as “America’s sweetheart” after her stunning performance in the 1984 Olympic Games at age 16, earned sizeable sums from product endorsements in the years after her triumph but had no health insurance when the disease struck.

Retton’s acknowledgment of her dire financial straits came as the Biden administration announced more than 21 million people signed up for health plans through the Affordable Care Act (ACA) marketplace during the most recent annual enrollment period (see page 3).

On NBC’s Today show, Retton attributed her lack of insurance coverage to 30 orthopedic surgeries, which count as “preexisting conditions,” as well as the financial strains of a divorce. “I couldn’t afford it,” Retton told host Hoda Kotb.

Options for the Uninsured

One of the selling points of the ACA was that it accepted uninsured people, even those with preexisting conditions, such as those Retton has. Furthermore, under the ACA, insurers are barred from charging higher premiums for people with preexisting conditions. Subsidies are based on household income.

Retton, a native of West Virginia who now resides in Texas, might have had difficulty qualifying for Medicaid in the Lone Star State because Texas has turned down the option to expand Medicaid. Retton, age 56, is too young and likely not disabled enough to qualify for Medicare.

Short-Term Insurance

Another option for Retton, and other cash-strapped Americans, is short-term health insurance. Expanding access to short-term plans was a priority of the Trump administration, which said such plans would increase choices for people with limited means.

Under a Trump rule issued in August 2018, insurers were allowed to sell short-term health insurance good for up to 12 months, with a renewal option of up to three years. However, people with preexisting conditions can be excluded from coverage. Though cheaper than ACA plans, which have long-term guaranteed renewability, they are also less comprehensive.

According to the National Association of Insurance Commissioners, 235,775 people were covered under short-term policies in 2022. However, the number of enrollees could be higher because carriers are not required to report enrollment data.

In July 2023, the Biden administration proposed a rule limiting short-term health policies to initial terms of no more than three months, with the option of an additional one-month renewal. The Biden rule would also bar a consumer from purchasing an additional short-term policy from the same insurer within 12 months.

Short-term plans are not available everywhere. Some states either ban them outright or make them so difficult to offer that insurers avoid them. Those jurisdictions include California, Colorado, the District of Columbia, Hawaii, Maine, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Washington.

Crowdsourcing Rescues Retton

Retton said on Today that she now has health insurance. To help her mother pay outstanding medical bills, Retton’s daughters set up a crowdfunding site that reported raising $459,234 in donations.

Kansas state Sen. Beverly Gossage, a licensed health insurance agent, says the options in the Obamacare marketplace are out of reach for many.

“We all sympathize with Mary Lou Retton’s health scare,” said Gossage. “We can assume she tried to find affordable rates before she developed pneumonia. Unfortunately, because of the ACA, the lowest-priced premium for her home state of West Virginia for a middle-income, 56-year-old woman would be over $14,650 annually, with an $8,000 out-of-pocket charge.”

Marketplace in Decline

Retton would have few choices in the ACA Marketplace, which is inaccessible except for the open enrollment period, and unsubsidized coverage is increasingly unaffordable, says Gossage.

“She had a narrow six-week window to purchase this insurance,” said Gossage. “Over the past 10 years, the ACA forced out most of the carriers, and rates are very high for all but those in the lower-income bracket.”

“A few have found relief in the short-term plan market, paying 70 percent lower rates than in the ACA market, but not everyone could qualify,” said Gossage. “It’s time to give Americans private, personalized, portable options from a truly competitive marketplace, without the federal government’s thumb on the scale.”

‘Attacking the Victim’

Jeff Stier, a senior fellow at the Consumer Choice Center, echoed Gossage’s sentiments. “Sadly, some of Obamacare’s most strident defenders are now insinuating Retton’s appeal for help was somehow inappropriate.”

“They refuse to accept that even someone who once achieved great success could face a series of challenges that could make Obamacare unaffordable,” said Stier. “Rather than acknowledging that the market for health insurance is so fundamentally distorted by Obamacare that it barely resembles a truly operating market, some have resorted to attacking the victim.”

An article on February 2 in The Mercury News, titled “Mary Lou Retton got $2 million in divorce but couldn’t ‘afford’ health insurance,” is an example of the attacks on Retton.

‘Coverage Does Not Equal Care’

Robert Henneke, executive director of the Texas Public Policy Foundation, says Retton’s case is not an isolated one and points to the ACA’s unfulfilled promises.

“Sadly, this type of tragedy has become all too common in the decade-plus since Obamacare became law,” said Henneke. “Coverage does not equal care, and the high cost and the loss of provider options under the ACA has left most Americans worse off than before.”

Bonner Russell Cohen, Ph.D. (bcohen@nationalcenter.org) is a senior fellow at the National Center for Public Policy Research.