American Historical Association members cancel their president, abandon scholarship, and erase the past, says Phillip W. Magness.

A bizarre string of events is unfolding at the American Historical Association (AHA). Last week, AHA president James H. Sweet published a column in the organization’s magazine on the problem of “presentism” in academic historical writing. According to Sweet, an unsettling number of academic historians have allowed their political views in the present to shape and distort their interpretations of the past.

Sweet offered a gentle criticism of the New York Times’s 1619 Project as evidence of this pattern. Many historians embraced the 1619 Project for its political messages despite substantive flaws of fact and interpretation in its content. Sweet thus asked: “As journalism, the project is powerful and effective, but is it history?”

Within moments of his column appearing online, all hell broke loose on Twitter.

Incensed at even the mildest suggestion that politicization is undermining the integrity of historical scholarship, the activist wing of the history profession showed up on the AHA’s thread and began demanding Sweet’s cancellation. Cate Denial, a professor of history at Knox College, led the charge with a widely-retweeted thread calling on colleagues to bombard the AHA’s Executive Board with emails protesting Sweet’s column. “We cannot let this fizzle,” she declared before posting a list of about 20 email addresses.

Other activist historians joined in, flooding the thread with profanity-laced attacks on Sweet’s race and gender as well as calls for his resignation over a disliked opinion column. The responses were almost universally devoid of any substance. None challenged Sweet’s argument in any meaningful way. It was sufficient enough for him to have harbored the “wrong” thoughts – to have questioned the scholarly rigor of activism-infused historical writing, and to have criticized the 1619 Project in even the mildest terms.

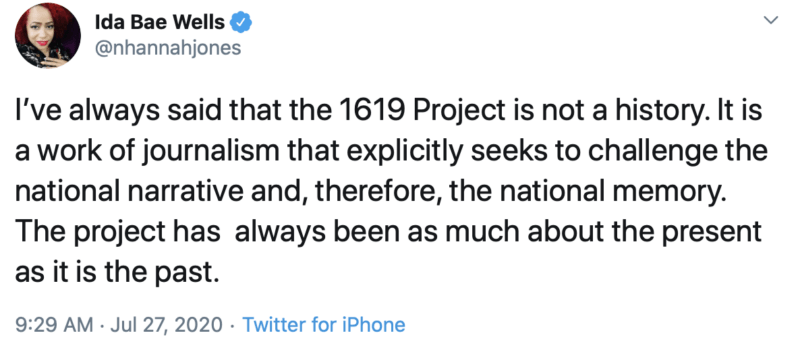

New York Times columnist and 1619 Project contributor Jamie Bouie jumped in, casually dismissing Sweet’s concerns over the politicization of scholarship with contemporary “social justice” issues. 1619 Project creator Nikole Hannah-Jones retweeted the attacks on Sweet, even though she has previously invoked the “journalistic” and editorial nature of her project to shield it from scholarly criticism by historians.

Other activist historians such as the New School’s Claire Potter retorted that the 1619 Project was indeed scholarly history, insisting that “big chunks of it are written by professional, award-winning historians.” Sweet was therefore in the wrong to call it journalism, or to question its scholarly accuracy. Potter’s claims are deeply misleading. Only two of the 1619 Project’s twelve feature essays were written by historians, and neither of them are specialists in the crucial period between 1776-1865, when slavery was at its peak. The controversial parts of the 1619 Project were all written by opinion journalists such as Hannah-Jones, or non-experts writing well outside of their own competencies such as Matthew Desmond.

The frenzy further exposed the very same problems in the profession that Sweet’s essay cautioned against. David Austin Walsh, a historian at the University of Virginia, took issue with historians offering any public criticism of the 1619 Project’s flaws – no matter their validity – because those criticisms are “going to be weaponized by the right.” In Walsh’s hyperpoliticized worldview, historical accuracy is wholly subordinate to the political objectives of the project. Sweet’s sin in telling the truth about the 1619 Project’s defects was being “willfully blind to the predictable political consequences of [his] public interventions.” Any argument that does not advance a narrow band of far-left political activism is not only unfit for sharing – it must be suppressed.

Within hours of the AHA’s original tweet of Sweet’s article, the cancellation campaign was in full swing. Predictably, the AHA caved to the cancellers.

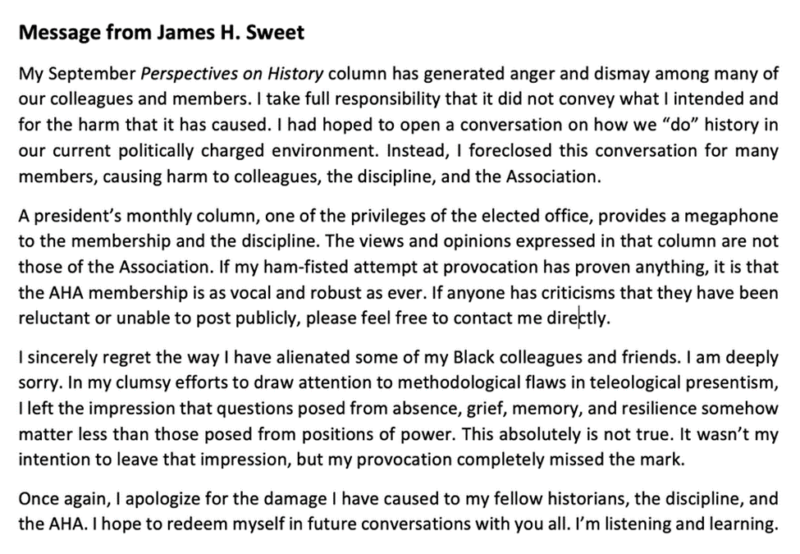

One day after the offending article went live, the AHA tweeted out a “public apology” from Sweet. It reads like a forced confession statement, acknowledging the “harm” and “damage” allegedly caused by simply raising questions about the politicization of scholarship toward overtly ideological activist ends. It did not matter that Sweet’s criticisms were mild and couched in plenty of nuance, or that they even came from a center-left perspective that also criticized conservative historians for politicizing the debate around gun rights. Sweet was guilty of pointing out that partisan political activism undermines scholarly rigor when the lines between the two blur, because the overwhelming majority of that activism inside the history profession currently comes from the political left. And for that, the very same activists extracted an obsequious apology letter. Its text, reproduced below, reads like a “struggle session” for academic wrongthink.

Sweet’s apology excited the activist wing of the profession, though it did little to placate their ire. The resignation demands continued, because Sweet’s apology was “insincere” and because his argument would be used by the “wrong” people – i.e. anyone who dissents from a particular brand of progressive activist orthodoxy. Simply criticizing the 1619 Project would play into the tactics of “Right-wingers, Nazis, and other bad-faith actors” who could use Sweet’s commentary “in the service of white supremacism and misogyny” announced Kevin Gannon, a historian who’s primarily known for scolding other scholars on twitter when they deviate from the profession’s far-left orthodoxies.

In this branch of academia, it does not matter whether the 1619 Project was truthful or factually accurate. The only concerns are whether its narrative can be weaponized for a political cause or used to deflect scrutiny of the same. As is often the case in the pseudo-moralizing political crusades of academia, the loudest demands against Sweet also came from the least-productive academics – historians with thin CVs and little in the way of original scholarly research to their names, although they do maintain 24/7 Twitter feeds of progressive political commentary.

Lora Burnett, one of the more vocal cancellation crusaders after the initial article posted, scoffed at Sweet, announcing “this apology was basically, ‘sorry I made you sad but I’m still right.’” She continued: “lamenting ‘inartful expression’ is apparently easier than admitting to flawed argument, unsupported claims, and factually incorrect assertions.” Note that Burnett and the other detractors never bothered to explain how Sweet’s argument was flawed or unsupported. Nor did they attempt to pen a rebuttal, which could have produced a constructive dialogue about the role of political activism in shaping historical scholarship. It was sufficient to denounce him as guilty for holding the wrong opinions. No matter the apology that Sweet made, the campaign to eject him from the history profession’s markedly impolite company would continue.

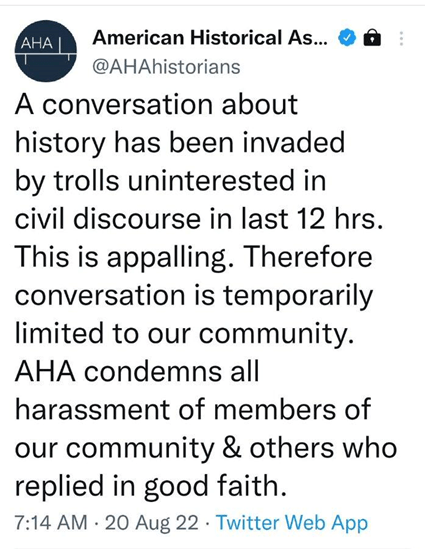

Meanwhile, the rest of the world began to take notice of the bizarre spectacle playing out at the main professional organization for a major academic discipline. As criticisms mounted on the AHA’s twitter feed, the organization moved to shut down debate entirely. They locked their twitter account, and posted a message to members denouncing the public blowback as the product of “trolls” and “bad faith actors.”

Keep in mind that only 24 hours earlier, the AHA had no problem with hundreds of activist historians flooding their threads with actual harassing behavior by bad faith actors. It tolerated cancellation threats directed against its president, calls to flood the personal email accounts of its board with harassing messages and denunciations of Sweet, and dozens of profane, sexist, and personally degrading attacks on Sweet himself. There were no AHA denunciations of those “trolls” or their “appalling” behavior, and no statements calling for “civil discourse” while the activist Twitterstorian mobs flooded the original thread with obscenity-laced vitriol and ad hominem attacks on Sweet.

Sadly, this type of unprofessional belligerence is now the norm on History Twitter. It would never be tolerated from any other perspective than the far-left, but it is valorized in the profession as long as it serves that particular set of ideological objectives.

The final irony is that the AHA only shuttered its twitter feed from the public when it could no longer restrict the conversation to the activist mob calling for Sweet’s cancellation. It’s the same brand of intellectual closure that Sweet’s offending column warned against in its final passage: “When we foreshorten or shape history to justify rather than inform contemporary political positions, we not only undermine the discipline but threaten its very integrity.”

Originally published by the American Institute for Economic Research. Republished with permission under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

For more great content from School Reform News.