By The Antiplanner

In 1964, the Japanese National Railways (JNR) was on a roll. The state-owned but largely unsubsidized company had just finished seven years of uninterrupted profits. Moreover, in 1964 it opened the Shinkansen (meaning new main line) between Tokyo and Osaka in time for the Summer Olympics. This exposed an international audience to the latest in Japanese technology in the form of the fastest trains in the world with top speeds of 130 miles per hour and average speeds as high as 86 miles per hour. These quickly became the envy of other countries, leading even the United States Congress to pass a law promoting high-speed trains in 1965.

Today, salarymen and tourists ride shinkansen the full length of Japan’s main island of Honshu as well as on the outer islands of Hokkaido and Kyushu. However, there is a dark side to the shinkansen. Like Darth Vader, who started out as a nice little boy who loved speed but whose life was corrupted by a power-hungry politician, the shinkansen was warped by politicians and ended up doing more harm than good to Japan’s economy.

Family resemblance? The E4 series train on the right often runs on the Joetsu and Nagano shinkansens, two of the most-expensive and least-used high-speed rail lines in Japan. Photo by Nanashinodensyaku.

Few Profits and Lots of Losses

To help finance the first shinkansen, now known as the Tokaido Shinkansen, JNR borrowed $80 million from the World Bank in 1961 and proudly finished paying off this loan in 1982. Based on this, it is popularly believed that the Tokaido line paid for all of its capital costs. But did it?

The 320-mile line was originally projected to cost ¥200 billion, but it ended up costing nearly twice that, or about $17 billion in today’s money. That cost was lower than it might have been because in 1940 JNR had purchased the right-of-way, dug some of the tunnels, and graded some of the route in an effort to build a high-speed line. The $80 million World Bank loan represented less than 9 percent of the total cost, with the rest coming from bond sales and loans from the Japanese government, particularly through the country’s postal banking system.

While the line carried lots of passengers, it isn’t clear how JNR could have repaid all of these loans as 1963 was the last year in history that it earned a profit. By 1972, it was losing (in today’s money) more than ¥10 billion (roughly $100 million) a year. To counter these losses, JNR repeatedly increased its passenger fares, which only accelerated the shift from rail to automobile travel.

JNR’s losses had several causes, but they all came down to politics. First, JNR operated railways on four of Japan’s islands, but only consistently made money on the main island where more than 80 percent of Japanese live. Japan’s politicians prevented it from shutting down money-losing lines on the outer islands. Second, politicians also prevented JNR from taking advantage of increases in worker productivity, forcing it to keep on its payrolls more than twice as many employees as it needed. Third, the prestige of the Tokaido Shinkansen led politicians in the rest of the country to demand that JNR build shinkansen lines into their prefectures and most of these lines failed to cover their operating costs, much less their capital costs.

Particularly notorious was the Joetsu Shinkansen, which terminates in the city of Niigata on Japan’s northern coast. Being built through mountainous territory, the line cost far more to build than the Tokaido line but carries only one-quarter as many passengers. Built at the behest of Kakuei Tanaka, a member of the Japanese Diet, the line terminates in Niigata, Tanaka’s hometown, whose metropolitan area has only around a million residents. Tanaka was prime minister of Japan for two-and-a-half years before being forced to resign in disgrace and tried and convicted for corruption, accepting bribes, and directing government construction contracts into his prefecture.

The original shinkansen wasn’t called a “bullet train” because it looked like a bullet; instead, it was shaped to look like a bullet to reflect the name bullet train, which had been coined in 1940 long before the trains were designed. Later trains had a duckbill shape aimed at reducing the noise when the trains entered tunnels. Photo by Nadate.

By 1986, JNR and its associated construction companies had racked up more than ¥5 trillion in debts building the Joetsu and other shinkansen lines. JNR also had more than ¥25 trillion in debts due to decades of losing money operating its trains. Along with a few other relatively minor debts, these totaled to ¥32.1 trillion or, in today’s dollars, about $550 billion. On top of this it had ¥5 trillion in unfunded pension obligations.

JNR had been able to borrow this money by using the land it owned as collateral. Japan’s land-use laws discouraged rural development by imposing a 150 percent capital gains tax on such development. This led to an incredible property bubble in which the land in Tokyo was valued to be four times greater than all of the land in the United States while the few hundred acres of land under the emperor’s imperial palace were estimated to be worth more than all of the land in California. Few properties actually changed hands; instead, as described by financial historian Edward Chancellor in Devil Take the Hindmost, companies like Toyota used their land holdings to undertake financial manipulations that actually earned them more profits than making and selling cars.

Even ignoring the bubble, by 1986 it was clear that JNR was unsustainable. First, it wasn’t even earning enough money to make interest payments on its debts. Second, thanks to growing auto ownership plus frequent fare hikes, passenger train ridership had been stagnant or declining since 1975, so there was no hope that the company would ever be able to repay that debt. Finally, including JNR and other state-owned companies, Japan’s total government debt had reached more than 50 percent of its gross national product—the JNR debt alone was about 30 percent of GNP—and this was considered unacceptably high in those days.

Privatization in Name Only

Japan’s Diet decided to fix this by reforming JNR in 1987. Although they called these reforms “privatization,” for many years it was privatization in name only and even today many of JNR’s former lines remain in state ownership.

Though JNR was a pygmy compared with many American railroads, for some reason the Diet decided that JNR’s problem was that it was too big. So they broke it up into nine different companies, seven of which were supposed to eventually be fully privatized.

First were six passenger railways, one for each of the three outer islands and three on the main island denoted JR Central, JR East, and JR West. Although these are all supposed to be separate companies, they all use the same JR logo, they all sell tickets for any of the companies’ trains, and some trains run through from the tracks of one company to another.

A seventh company operates freight trains on all of the islands. Rails carry only about 4 percent of freight in Japan so this wasn’t very important or profitable. The eighth company, called the Shinkansen Holding Company, owned the shinkansen lines and leased them to the passenger railways.

Finally, the JNR Settlement Corporation was supposed to make good on JNR’s debts by selling stock in the JR companies and surplus JNR land. It hoped that the JR companies would be able to repay about ¥14.5 trillion of the debt and that land sales would earn another ¥7.7 trillion. Sale of stock in the JRs was expected to earn ¥1.2 trillion. This left ¥13.8 trillion for the taxpayers to absorb.

Equal to $235 billion in today’s money, that ¥13.8 trillion was a lot to ask the taxpayers of a relatively small country to pay for railways that they were using less and less each year. Unfortunately for the taxpayers, it didn’t even work that well.

The settlement corporation decided that about 9,300 hectares, or 23,000 acres, could be sold. At the prices they were expecting, that works out to about $4.6 million an acre in today’s money. Only a few American downtowns have land that is worth that much, and while 52 acres of this land was in downtown Tokyo, most of it was elsewhere.

According to economist Yukihide Okano, the settlement company’s initial attempts to sell land led to prices so high that it was “criticised for boosting land prices.” To prevent that from happening, the company “was forced to refrain from offering land by bids and had to sell the land to local governments for public purposes at more ‘reasonable’ prices.” Another view was that change in policy was due to “collusion and land giveaways.”

My own view is that the sale of so much land at one time threatened the Japanese bubble economy. Putting more land on the market does not increase prices; it reduces them. I don’t believe it is a coincidence that the property bubble collapsed right after the settlement company started to sell land. I suspect that the threat of a large-scale land sale led people to realize that Tokyo really wasn’t worth four times as much as the entire United States. This had the effect of pricking the bubble, leading to years of economic stagnation.

That stagnation devastated the stock market, making it difficult for the settlement company to sell stock in the JRs. The first initial public offerings failed. The three central island JRs were not fully privatized until 2004. One of the outer island JRs was privatized in 2016. The other two along with the freight company remain in government ownership and receiving government subsidies.

The Shinkansen Holding Company agreed to sell the high-speed rail lines to the JRs in 1991. Although it nominally received a fair price for them—about $100 billion—it had to agree to allow the companies to pay it off over 60 years. Though the companies plan to pay it off sooner, these generous terms meant the initial revenue was very low.

From the railways’ point of view, the one good thing to come out of reform was that the deregulated JRs were allowed to shed unnecessary workers. Employment fell from more than 400,000 under JNR in 1980 to 191,000 in 1994. This allowed the three Honshu JRs to become consistently profitable without fare increases, although they all still have large long-term debts on their ledgers.

The other JRs, however, continued to lose money. Despite some sales of land and stocks, by 1998 the settlement corporation’s debt had reached ¥28 trillion ($480 billion in today’s money). Thus, the so-called privatization only managed to reduce the debt by about 12 percent. At that point, the Diet abolished the settlement company, absorbed the debt, and agreed to continue to subsidize the freight and outer island JRs.

Economic Stimulus or Drag?

One of the government’s responses to the stagnation that followed the collapse of the property bubble was to “stimulate” the economy by building more high-speed rail lines. Since JNR reform, it has built three new lines plus two “mini-shinkansens,” upgrades of conventional tracks (which in Japan are narrow gauge) to run trains as fast as 80 miles per hour.

The national government funds about two-thirds of the construction costs with local governments expected to fund the other third. The governments hope to offset some of these costs with lease fees from the JRs that operate them, but no one expects those fees to repay the loans required to build the lines.

These new lines haven’t been very stimulating. Although Japan’s stagnated post-bubble years are often called the “lost decade,” it was really at least two decades. According to data published by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), Japan’s economic growth per capita was slower than any developed nation except Switzerland in the 1990s and slower than any developed nation except Italy in the 2000s. Growth picked up in the 2010s but was still slower than average.

Other than providing some short-term construction jobs, there’s no reason to think that new shinkansen lines would stimulate the national economy. Studies have found that opening new shinkansen lines boosts the economies of cities they serve, but at the expense of slower growth in cities not served by the lines. As one study that compared Japan’s experience with the planned California high-speed rail line concluded, “the economic development impacts of the California HSR project are likely to be more redistributive than generative.” (The study did say that there may be net benefits if you believe that denser development stimulated by the rail lines will increase productivity, but in the light of the pandemic not many people believe that anymore.)

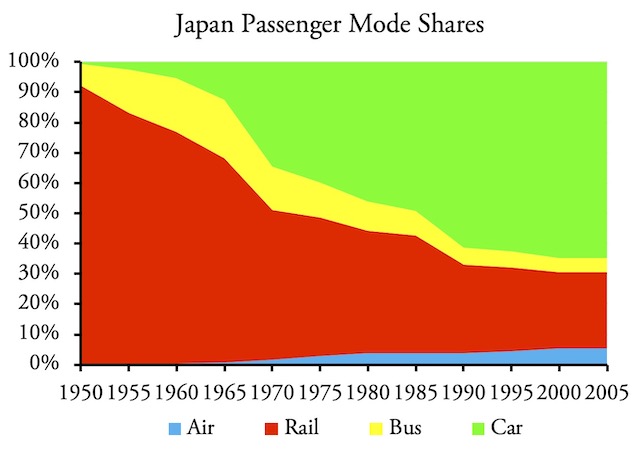

Construction of new shinkansen lines did nothing to stop the growth of auto travel and decline of rail travel in Japan.

Nor have the shinkansen truly revolutionized passenger transportation in Japan. In 1960, when construction on the Tokaido line began, rails carried 77 percent of passenger travel while automobiles carried just 5 percent. The automobile’s share steadily grew at the expense of rail, with autos carrying 65 percent of passenger-miles in 2005 while rails carried just 25 percent. Air travel also grew from near-zero in 1960 to more than 5 percent in 2005. Unfortunately, the Japanese government stopped publishing these data after about 2007, but there’s no reason to think these trends would have changed.

MagLev: The Next Boondoggle

Although JR East, which operates three shinkansen lines, is bigger than JR Central, the latter’s Tokaido line is still by far the most popular shinkansen, carrying 40 percent of all high-speed rail riders in the country. JR Central planned to completely pay off the cost of its purchase of the line by 2015, after which it expected to make enormous profits. Instead of returning those profits to shareholders, it decided to build an even faster maglev line in the Tokaido corridor. This will be known as the Ch?? Shinkansen.

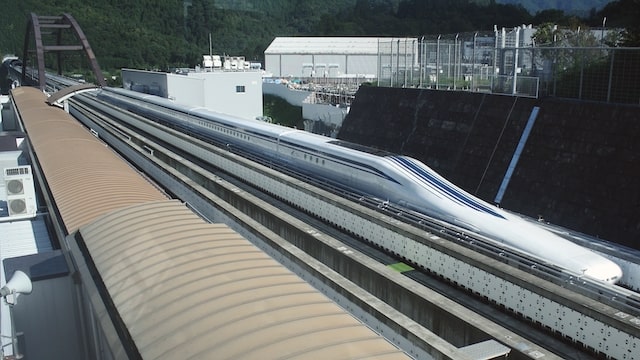

Currently, the fastest trains on this route reach top speeds of 186 miles per hour and take 3 hours and 21 minutes to get from Tokyo to Osaka, an average speed of 136 miles per hour. The maglev train would have top speeds of 315 miles per hour and take as little as 67 minutes to get from Tokyo to Osaka, for an average speed of 286 miles per hour.

Construction has begun on some of the tunnels for a maglev line that will cost five times as much money and require five times as much energy to operate as the parallel Tokaido Shinkansen. Photo by Saruno Hirobano.

Originally expected to cost about ¥5.1 trillion, the costs soon inflated to ¥10 trillion (about $100 billion), more than five times the inflation-adjusted costs of the Tokaido Shinkansen. JR Central expected to complete the first section of the line, from Tokyo to Nagoya, by 2027 and extend the line to Osaka by 2045. Although JR Central said it would finance the line itself, the government offered a ¥3 trillion low-interest loan in exchange for JR Central accelerating its timetable for the Osaka segment by eight years.

Critics in Japan see the Chuo Shinkansen as just another way to feed the “construction state.” The maglev line would not only be “extraordinarily costly but also an abnormally energy-wasting project, consuming in operation between four and five times as much power as the Tokaido Shinkansen,” write economist Aoki Hidekazu and engineer Kawamiya Nobuo.

“Since the 1960s, Japan’s major construction projects have become vastly more costly and less efficient,” the two argue, and the Chuo Shinkansen is the crowning achievement of this trend. “Deficit-breeding, energy-wasting, environmentally-destructive, and technologically unreliable, the Linear Shinkansen project must be considered a guaranteed fiasco.” They argue that the Chuo line won’t earn enough money to pay off its costs, but it will attract enough passengers away from the Tokaido line to put that one in the red as well.

The high energy cost of the maglev train is especially complicated by the closure of nuclear power plants following the Fukushima disaster. The coronavirus pandemic, which reduced shinkansen ridership by as much as 84 percent and led JR Central to declare its first money-losing year since it was created in 1987, makes a new line even more problematic.

The Shinkansen Addiction

The original shinkansen put Japanese railways in the world spotlight just at the moment when increasing auto ownership and bus travel began eating into JNR ridership and profits. To stay in the spotlight and meet local political demands, Japan continued building more shinkansen lines despite the fact that few if any carried enough riders to pay their way. The result was that JNR had become unsustainable by 1986.

JNR reform in 1987 allowed the separate railways to save money by laying off more than half their work forces, which enabled at least three of the seven JRs to become profitable without fare increases. This halted the decline in ridership that JNR had been suffering and even allowed some ridership gains. However, Japan’s falling population and increasing auto ownership meant that future ridership growth would be slow at best.

Reform did little to help Japan’s debt problems. Thanks partly to continuing subsidies to the non-privatized JRs and for shinkansen construction, Japan’s debt now exceeds ¥1 quadrillion, or more than $10 trillion. While some American economists are nervous because U.S. debt now exceeds 100 percent of gross domestic product, Japan’s debt is more than 250 percent of its GDP, the most of any country in the world. The current debt is partly due to reconstruction efforts after the T?hoku earthquake, but the debt before the earthquake was bad enough that Standard & Poor’s downgraded the country’s bond rating, saying that the government “lacks a coherent strategy” for dealing with its debt.

In fact, it has a strategy: build more shinkansen lines in the hopes that it will stimulate the economy. Japan’s political leaders and its construction state are addicted to the shinkansen and this addiction is hurting the country.

Originally published by The Antiplanner. Republished with permission.