By Kevin Dayaratna

On his very first day in office, President Joe Biden issued an executive order resurrecting the Obama-era social cost of carbon, intended to quantify the economic impact of climate change.

The administration on Feb. 26 issued an interim estimate reporting that these damages are approximately $51 per metric ton of carbon dioxide emissions.

Dubbed by some as “the most important number you’ve never heard of,” the social cost of carbon is defined as the economic damages associated with a ton of carbon dioxide emissions across a particular time horizon.

That metric, relied upon heavily by the Obama administration, has been used as the basis for regulatory policy in the energy sector of the economy.Three sets of statistical models are used to estimate the social cost of carbon: the DICE model, the FUND model, and the PAGE model.

During the Obama administration’s tenure, we took two of those three models in-house at The Heritage Foundation’s Center for Data Analysis.Since any model is only as good as the assumptions from which it’s composed, we decided to examine the sensitivity of the administration’s social cost of carbon estimates based on choices to various fundamental assumptions.

In particular, in addition to the uncertainty associated with the models’ central components, social cost of carbon estimates are based on very questionable assumptions regarding the climate’s sensitivity to carbon dioxide emissions, naive projections reaching 300 years into the future, and ignorance of discount rate recommendations by the Office of Management and Budget regarding cost-benefit analysis.

My former colleague David Kreutzer and I first examined the robustness of the DICE model based on changes to those assumptions. Our analysis found that, under very reasonable assumptions, the model’s estimates of the social cost of carbon can drop by 30% or more.

Read Heritage scholars’ examination of the DICE model.

Subsequently, we examined the FUND model. In our initial inspection of the model, we found a mistake in the model’s climate-sensitivity specification that reduced the model’s social cost of carbon estimates by as much as 10%, which forced the Obama administration to open the entire class of modeling up to public comment.

Upon further examination of the model, however, we found that the FUND model is just as sensitive, if not more so, to choices of climate-sensitivity distributions and discount rates than the DICE model.

Read Heritage scholars’ examination of the FUND model.

Furthermore, our close examination found that, unlike the DICE model, the FUND model also computes the benefits from climate change, taking into account positive agricultural feedback effects associated with carbon dioxide emissions.

In fact, we found that under very reasonable assumptions, those benefits can outweigh the costs, suggesting that the social cost of carbon can indeed be negative.

The policy implication of a negative social cost of carbon is that the government should not be taxing carbon dioxide emissions, but should be subsidizing it instead.

We don’t take the position that the government should either be taxing or subsidizing carbon dioxide emissions, but the sheer fact that that the model can illustrate either, under very reasonable assumptions, illustrates how susceptible these models are to user manipulation.

Our critical analysis of the models were not only published at The Heritage Foundation, but also in peer-reviewed academic and industry journals as well.

Read Heritage’s peer-reviewed analysis of the social cost of carbon.

Read Heritage’s other analysis of the social cost of carbon.

And these are not the only assumptions that impact the robustness of the social cost of carbon. In more recent research, my co-authors (Pat Michaels and Ross McKitrick) and I looked at a separate aspect of the FUND model; namely, its agricultural productivity component. Specifically, this aspect of the model captures the level of agricultural benefits from carbon dioxide emissions discussed above.

In this work, published in yet another peer-reviewed journal, Environmental Economics and Policy Studies, we found that these assumptions were decades old. Under more up-to-date assumptions, we found that the social cost of carbon is effectively zero and may even be negative.

The Biden administration is also looking to use similar models to estimate the social cost of methane and social cost of nitrous oxide.

My colleague Nick Loris and I also performed similar robustness analysis for these models as well. Our results tell the same story: Assumptions made by modelers can drastically change the purported estimates and thus beef up the damages as much as they want.

Over the past several years, we discussed these issues in front of Congress on a number of occasions and were glad to see the Trump administration recognize this work.

Read Kevin Dayaratna’s congressional testimony on the issue.

That, in a nutshell, is why the social cost of carbon is the most useless number you’ve never heard of. Don’t be deceived by the Washington establishment’s use of such an unreliable metric to rubber-stamp its energy policy agenda.

Although the social cost of carbon is based on an interesting class of statistical models, no matter what estimate the Biden administration provides, the assumptions used to generate it can almost surely be manipulated to give lawmakers virtually any other (even negative) estimate of the social cost of carbon, thereby predicting anything, ranging from little warming and continued prosperity to catastrophic warming and immense disaster.

We at The Heritage Foundation look forward to conducting similar sensitivity analysis when the Biden administration issues its final estimates of the social cost of carbon in the coming months.

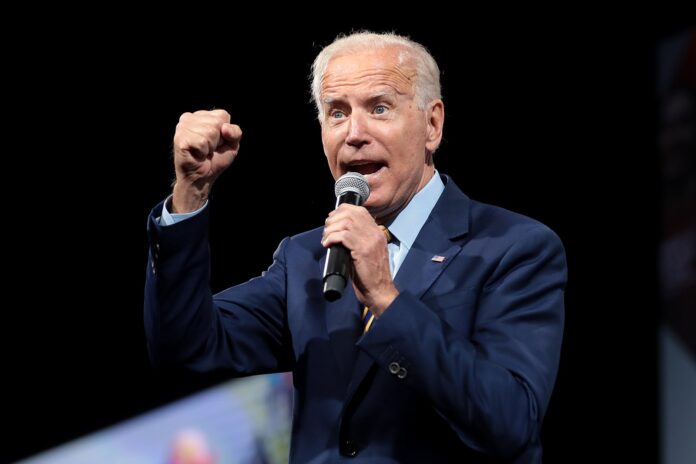

Kevin Dayaratna explores the boundaries of policy, statistics, and economics as principal statistician, data scientist, and research fellow at The Heritage Foundation’s Center for Data Analysis.

This article was originally published on The Daily Signal and is reprinted with permission.