When President Joe Biden announced he would withdraw all U.S. troops from Afghanistan by the 20th anniversary of 9/11, GOP hawks like Sens. Mitch McConnell and Lindsey Graham responded predictably.

“Grave mistake,” muttered McConnell.

“Insane,” said Graham, “dumber than dirt and… dangerous.”

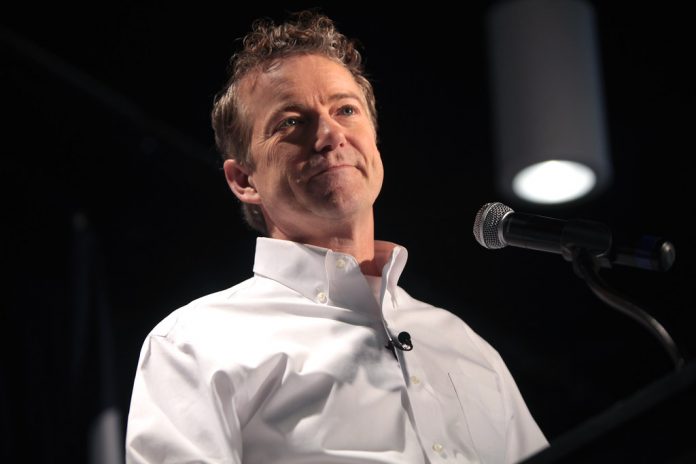

Of more interest were the responses of conservative Republicans who commended the president. Among them were Sens. Rand Paul, Ted Cruz, Josh Hawley and ex-Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, a group that contains several potential candidates for the GOP nomination in 2024.

Donald Trump himself weighed in Sunday, saying Biden’s decision was “wonderful,” but Joe should have stuck to Trump’s May 1 deadline for withdrawal from Afghanistan.

Adding a veteran’s voice to the broad consensus was the American Legion which called for an end to America’s “forever war,” and repeal of congressional authorizations to fight this war.

While many older Republican leaders remain wedded to a Bush foreign policy, some of the prospective leaders of the party seem to be adopting their own versions of “America First.”

Opportunity may be at hand. The door may be open for a leader to articulate a new U.S. foreign policy vision, beginning with a review of our Cold War commitments that became irrelevant with the collapse of the Soviet Empire and breakup of the Soviet Union three decades ago.

Consider. NATO, which dates back to 1949, today contains 30 allied nations, while U.S. security treaties with South Korea, Japan, the Philippines, Australia and New Zealand all date back to the 1950s.

How do all these war guarantees to other nations secure our vital interests, when our first vital interest is to stay out of any great war?

According to The New York Times, a 2020 survey by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs found, “Republican voters preferred a more nationalist approach, valuing economic self-sufficiency, and taking a unilateral approach to diplomacy and global engagement.”

Almost half of Republicans surveyed agreed that the “United States is rich and powerful enough to go it alone, without getting involved in the problems of the world.”

A survey by pollster Tony Fabrizio found that “only 7 percent of Republicans prioritize national security and foreign policy issues.”

The opportunity is transparent.

As domestic concerns are predominant — the COVID-19 pandemic, the invasion across our Southern border, soaring crime rates, race relations as raw as they have been in decades — it is time for U.S. statesman to look out for America and Americans first, and let the world look out for itself.

Biden is a perfect foil — a trans-nationalist and globalist committed to the whole panoply of old security treaties and war guarantees that had existed for a generation even before he came to Washington 50 years ago.

The favorable reaction to his pullout from Afghanistan should have told Biden that. And it should tell Republicans that now may be the time to seize the moment.

Let Republicans openly reject the Biden administration’s unilateral commitments to fight China for tiny reefs claimed by the Philippines in the South China Sea and Japan in the East China Sea.

And, surely, it is time for that “agonizing reappraisal” of NATO promised by Secretary of State John Foster Dulles in the 1950s.

Why are we still committed, under NATO, to go to war with Russia on behalf of Germany, when the Germans, with their Nord Stream 2 pipeline, are doubling their dependency on Russia’s natural gas?

According to the Atlantic Council President Richard Haas, the U.S. should abandon its policy of “strategic ambiguity” as to what we would do if China attacks Taiwan — and make a commitment to defend Taiwan.

But why should the United States commit to a war with China for an island President Richard Nixon conceded in 1972 was part of China?

Among the reasons Trump won in 2016 is that he offered a foreign policy of easing tensions with Vladimir Putin’s Russia, getting us out of the endless wars of the Middle East, and making free-riding allies pay the cost of their own defense.

Yet, though, currently, we have commitments to fight for 29 NATO nations, there is a push on among our foreign policy elites to add new nations, such as Ukraine, Georgia, Moldova, Finland and Sweden.

But, again, why surrender our freedom to decide whether to fight?

As for South Korea, Japan and Taiwan, each could build a nuclear deterrent, as Israel, Pakistan and India have done. If a war were to be fought with China that could go nuclear, why would we want to be a mandatory participant?

Among the reasons the U.S. emerged victorious in the 20th century was that we stayed out of the two world wars longer than any of the other great powers.

“Don’t ever take a fence down until you know the reason it was put up,” wrote G. K. Chesterton. Sound advice. But some of these fences were built before most Americans were born, and the world has changed.

Patrick J. Buchanan is the author of “Nixon’s White House Wars: The Battles That Made and Broke a President and Divided America Forever.” To find out more about Patrick Buchanan and read features by other Creators writers and cartoonists, visit the Creators website at www.creators.com.

COPYRIGHT 2021 CREATORS.COM

Pat Buchanan supports nuclear weapons proliferation instead of the US being a defendant of the world’s liberty? Sounds to me like not a very well-thought-out position.

Thanks for your comment, Ohio Historian.

Buchanan’s point is indeed that the United States is not the “defend[er] of the world’s liberty.” His argument is that our nation should defend the liberties only of its own people, which is a sufficiently difficult and costly job in itself. Our nation’s involvement in others’ fights should be limited strictly to what serves the defense of Americans’ liberties, Buchanan avers. Buchanan is also clear in stating in his writings that the national government’s job is to protect our liberties, not our “interests.” It is up to individuals and their associations to protect their personal and corporate interests, Buchanan would argue.

The claim of defending “America’s interests” is generally a fig leaf for the use of other people lives and treasures in the interests of powerful businesses (that donate money to influence elections), not Americans in general.

According to Buchanan’s premises, then, nuclear weapons proliferation is a concern to the extent that it threatens Americans’ liberties (again, not “interests”). Buchanan clearly indicates that he does not see this proliferation as a threat to American liberty. Those who see it as such are welcome to offer scientific evidence that it is so. It is certainly a discussion worth having–and not a topic that can be dismissed without discussion.

As such, one can see Buchanan’s position as being well-thought-out, regardless of whether one agrees with it.