By Raheem Williams

In recent years, the Florida legislature has led on multiple reforms to the Florida Retirement System, but the pension system is still failing to fully fund retiree benefits and the state’s pension debt payments are costing taxpayers more and more each year. During the 2021 legislative session, Florida lawmakers again recognized the need for public pension reform, but, unfortunately, even the proposed legislative plan, which ultimately failed to pass, would not have meaningfully impacted the state’s growing unfunded pension liabilities.

In future retirement reform efforts, Florida policymakers trying to address the challenges facing the Florida Retirement System should recognize that a more collaborative process, which brings together important stakeholders like taxpayer advocates, public employee unions, and retirement experts, is a necessary component to enacting comprehensive reforms.

Using actuarial modeling of the Florida Retirement System (FRS), the Pension Integrity Project identified key policies and practical solutions that could both provide retirement security for state workers and reduce long-term costs for taxpayers.

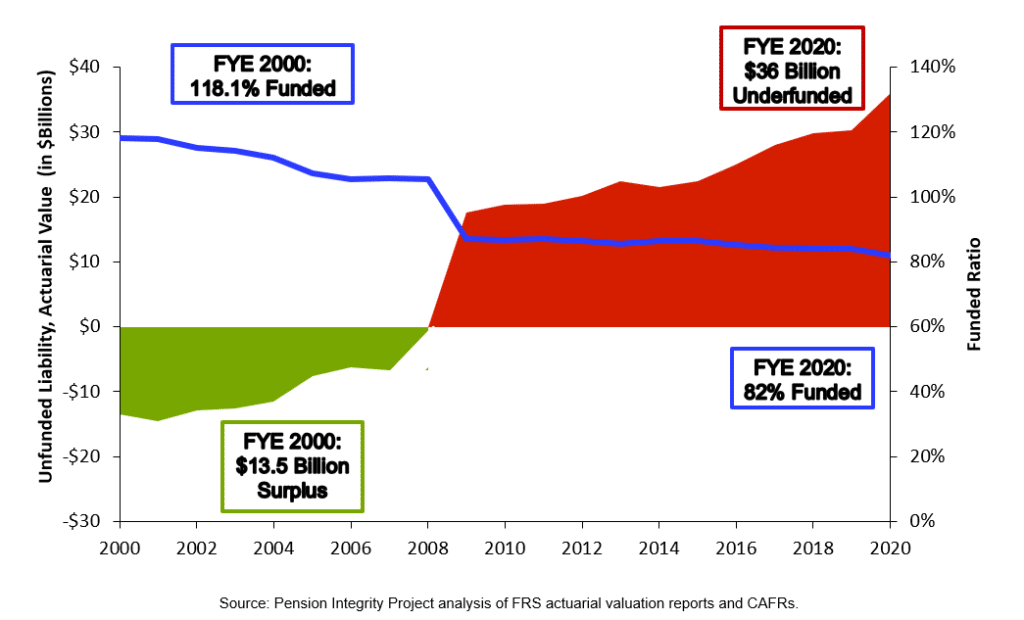

In 2000, the FRS defined benefit pension plan for state and local government employees had a surplus of $13.5 billion for employee retirement benefits and was 118 percent funded. Today, the pension plan stands at just 82 percent funded, meaning it has only 82 cents of every dollar it owes in retirement benefits.

The Florida Retirement System also has a total of $36 billion in unfunded liabilities, more simply viewed as public pension debt. Perhaps even more concerning, FRS’ debt is growing quickly and over $6 billion of the system’s debt has accumulated in the last two years, as shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1 – Florida Retirement System’s Pension Plan Debt Accrual

This pension debt is the result of a variety of factors, including policymakers waiting too long to adjust to changing market conditions and economic trends.

In 2021, the Florida legislature considered Senate Bill 84, a pension reform bill that was a priority of Senate leadership. The reform bill aimed to stop the state government from accumulating future pension debt. The measure, which passed the State Senate, would not have fundamentally altered the conditions driving the rapid growth of FRS’ unfunded pension liabilities and ultimately the legislation failed to receive consideration in the House before the legislature adjourned.

If enacted, SB 84 would have completely closed the FRS Pension Plan to most future hires. This move would have built upon Senate Bill 7022, which was enacted in 2017 and switched the FRS enrollment default from the defined benefit (DB) plan to the primary defined contribution (DC) plan known as the FRS Investment Plan.

The Pension Integrity Project evaluated SB 84 during the 2021 session, identified the bill’s shortcomings, and proposed substantive areas of improvement. Our analysis found that closing the defined benefit option for new workers would produce some long-term risk reduction for taxpayers because the remaining defined contribution plan would have fixed costs and could not accumulate debt, but this positive impact would take decades to realize. That’s because closing the FRS Pension Plan to new employees alone would do nothing to address the system’s existing debt, which would continue to grow even if the FRS Pension Plan was closed. Thus, SB 84 was not a sufficient proposal to meet the state’s debt challenges and additional provisions would be needed to solve the problems that helped create the system’s $36 billion of debt. Senate Bill 84 also met serious opposition from special interest groups, primarily public education associations. Although the concerns levied by these groups were generally misdirected and sometimes ill-informed, including these groups in future reform efforts may help minimize future policy conflict.

With the failed 2021 attempt at retirement reform now in the rear-view mirror, Florida is still in need of a polciy solution to its public pension problems. Below we outline a few of the issues that still face both the FRS defined benefit pension plan and the FRS Investment Plan. Using actuarial modeling we present our long-term evaluation of SB 84’s proposed closure of the existing defined benefit plan for new workers, along with an alternative reform option that would better address the challenges facing stakeholders and the state of Florida. Under the Pension Integrity Project alternative reform option, future workers would still have the option to participate in a defined benefit plan and, with the introduction of improved risk and contribution policies, the alternative would reduce long-term costs and financial risk in ways that SB 84 would not have achieved.

Florida Retirement System’s Funding Challenges

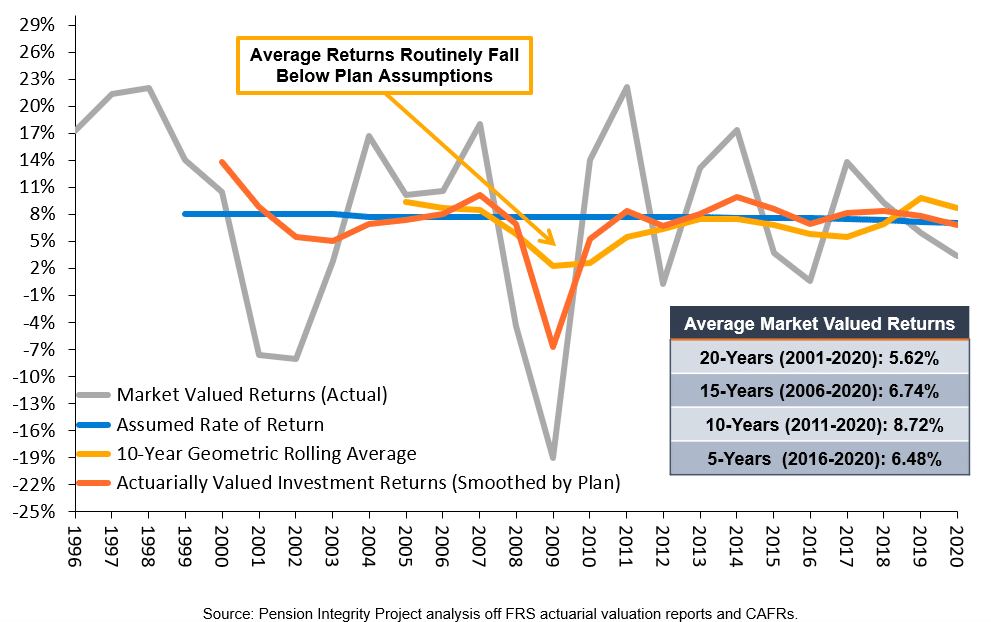

The first pension-funding challenge that Florida policymakers need to face is the system’s unrealistic expectations for market returns. Over the last 13 years, $16.4 billion of Florida’s pension debt has come from failing to meet overly optimistic investment return assumptions.

Every year that FRS fails to meet its investment return assumption, public pension debt grows. Adopting more realistic investment return assumptions should be a top priority for state policymakers because this problem will likely continue to add debt to the system if it is not addressed.

FRS historically assumed an investment return rate as high as 8 percent before lowering the assumption to 7.75 percent in 2004. The system has adjusted the investment return assumption annually since 2014, to reach the current assumed rate of 7 percent for 2021.

Although progress has been made on this front, the system’s expectations are likely still too high for the long term. The FRS modeling that was developed in 2017 by Milliman and Aon Hewitt found that the 50th percentile geometric average annual long-term future returns would be in the 6.6 percent-to-6.8 percent range. Models developed in 2018 by Milliman and Aon Hewitt showed FRS should expect average annual long-term future returns in the 6.4-6.7 percent range, yet the FRS Actuarial Assumption Conference adopted a 7.4 percent return assumption. Presenters at the 2020 FRS Actuarial Conference suggested return assumptions within the range of 6.46 percent (Aon) to 6.56 percent (Milliman).

The Florida Retirement System’s average investment return for the last 20 years was 6.81 percent, well below the current 7 percent assumption (see Figure 2). The market forecasts for the next 10 to 15 years indicate that FRS is more likely to see returns around 6 percent. That means FRS is still likely to experience perpetually growing pension debt unless the system’s investment return assumptions are reduced even further.

Figure 2 – Florida Retirement System’s Investment Return History, 1996-2020

Source: Pension Integrity Project analysis of FRS actuarial valuation reports and CAFRs.

Florida’s policymakers also need to address the amortization policies of the state’s retirement system. Long debt-payment schedules have contributed to Florida’s inability to pull itself out of its pension debt over the past decade. It is expensive to hold large amounts of unfunded pension liabilities and the longer the state takes to pay off these pension debts, the more it will cost taxpayers in the long run. Florida policymakers need to address this challenge going forward by shortening amortization schedules for any newly accrued debt.

Furthermore, the existing defined contribution option, the FRS Investment Plan, which is offered to new hires, has major problems of its own that are worth tackling as part of any future retirement reform effort. The employer and employee contribution rates for the Investment Plan are low relative to typical private-sector standards, suggesting that many government employees could eventually retire without having sufficient post-retirement income.

Retirement professionals recommend contributing between 10 to 15 percent of an employee’s annual income toward the main retirement account for those participating in Social Security. FRS Investment Plan members, however, contribute just 3 percent of their salaries to their individual retirement accounts, with the state contributing another 3.3 percent. In total, about 6.3 percent of an employee’s pay is going into employees’ retirement accounts, far below even the low end of industry norms.

Sadly, many workers in the defined contribution plan may be under the false impression that they are saving enough for retirement. If these issues are not addressed, many FRS Investment Plan members may find themselves with income replacement that is substantially below their needs or expectations when they retire.

Evaluating Retirement Reform Options

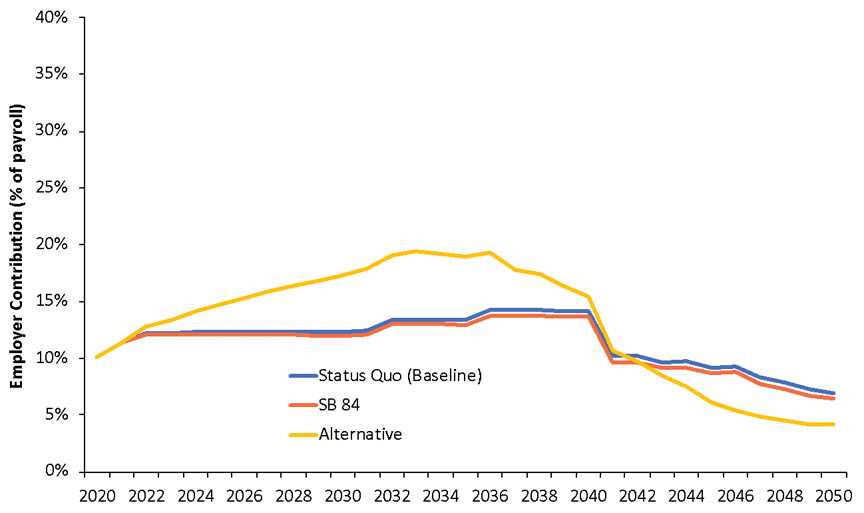

The Pension Integrity Project has incorporated the above reform elements into actuarial modeling to demonstrate the varied impacts of potential reforms. The analysis below displays the contribution and funding outcomes of three different options:

- Status Quo (baseline)—Represents the current state of FRS, no changes are made.

- Senate Bill 84 (as passed in Senate)—Closes the DB Pension Plan to all new hires except special risk members. Includes no other funding or risk-related policy changes.

- Alternative (a better option for future retirement reform efforts) — This option gives all new hires, regardless of class, the choice between a new, risk-managed, 50/50 cost-sharing FRS Pension Plan and a higher funded FRS Investment Plan. It gradually lowers the FRS assumed investment rate of return to 6 percent and adopts 15-year layered amortization for any new unfunded liabilities as risk-reduction measures for the legacy defined benefit plan.

Reason’s analysis of SB 84 during the legislative session indicated that simply closing the state’s defined benefit plan for new workers would do little to affect contributions into the fund over the next 30 years and therefore would not sustainably improve the state’s ability to fully fund FRS amid a volatile and unpredictable financial future.

By contrast, the alternative reform proposed in this analysis would gradually reduce the Florida Retirement System’s assumed rate of return and would reduce the amortization period used for paying down any new pension debt. These moves would noticeably alter the state’s contributions to the plan over the next three decades. As shown in Figure 3, if we assume a 7 percent constant rate of return over 30 years, the alternative will require higher employer contributions upfront to accelerate the elimination of unfunded liabilities. But in return, rates level out near or below the status quo and SB 84 over the mid-and long-term, a prudent tradeoff to eliminate risk.

Figure 3 – State Contributions for Reform Options if Experience Matches FRS Assumptions

Source: Pension Integrity Project actuarial forecast of FRS. The state is assumed to make 100 percent actuarially required contributions. Values are adjusted for inflation.

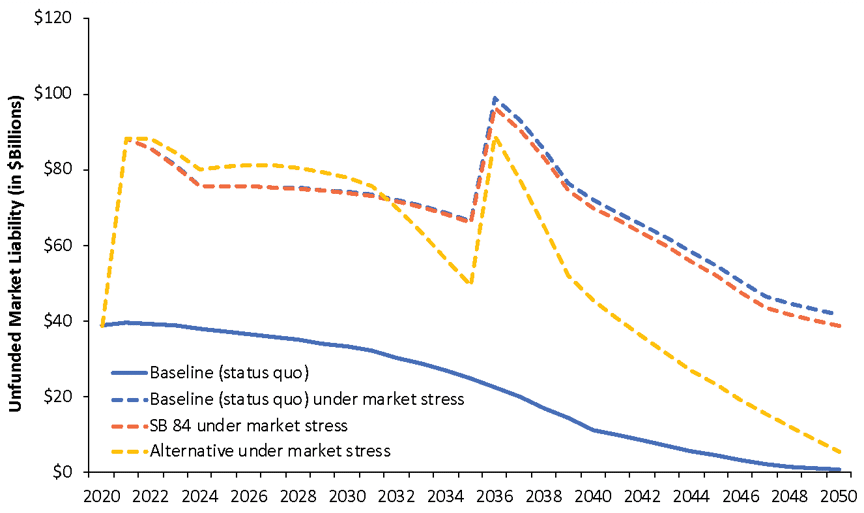

Assuming economic uncertainty in the decades ahead, the next figure models two recessions, in 2021 and 2036, and 6 percent constant returns in the remaining years. Figure 4 shows that the changes proposed in SB 84 would make little difference to year-to-year state contributions. Since these rates would be based on the same assumptions and amortization policies that generated the system’s current $36 billion in pension debt, SB 84 would not have prevented further debt from accruing if FRS’ assumptions prove inaccurate.

Figure 4 – Contributions for Reform Options in Volatile Market Scenario

Source: Pension Integrity Project actuarial forecast of FRS. The state is assumed to make 100percent actuarially required contributions. Values are adjusted for inflation.

Under the proposed alternative reform the state would agree to higher up-front contributions that would be more reflexive to market returns, as shown in Figures 3 and 4. This change would be the key to establishing a more resilient retirement system that could maintain a path to full funding even under market stress scenarios. Actuarial modeling of the system’s unfunded liabilities (see Figure 5) shows that outside of the idyllic and unrealistic status quo assumptions, FRS is still very vulnerable to the same pressures that caused the system’s $36 billion shortfall in the first place. The reforms proposed in SB 84 would have done nothing to rectify this issue.

Committing to more realistic return assumptions and accelerating amortization payments, however, would insulate the system from future market volatility. Adopting the reform options outlined in our proposed alternative would ensure that Florida is on a path to reducing unfunded liabilities, even while facing a volatile and unpredictable future.

Figure 5 – Florida Retirement System Funding Under Reform Options

Source: Pension Integrity Project actuarial forecast of FRS. The state is assumed to make 100 percent actuarially required contributions. Values are adjusted for inflation.

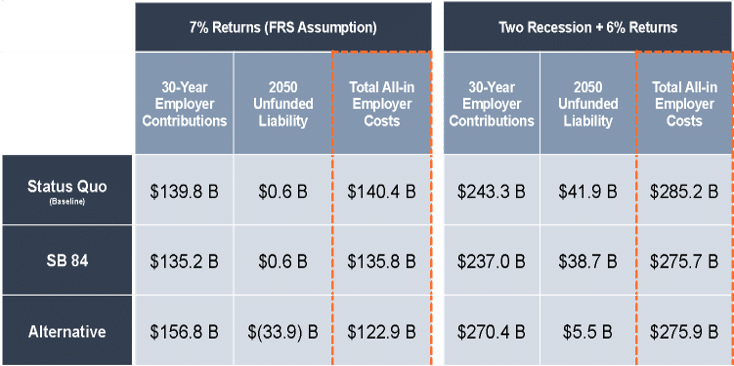

Table 1 shows that under the current 7 percent investment return rate assumption, SB 84 would have only marginal reduced the system’s debt and would have failed to generate the same cost savings as the alternative reform design under most market scenarios. Under stress-tested scenarios, SB 84 outperforms the status quo but fails to contain the overall debt, leaving taxpayers still exposed to major risk of continuing unfunded liabilities at the end of the 30-year forecast period.

Florida is facing the very real possibility of dedicating hundreds of billions of additional dollars toward FRS over the next 30 years. Apart from the unrealistic status quo investment return assumption, these extra funds would make practically no progress in reducing the state’s expensive pension debt. While requiring a commitment of higher annual contributions upfront, the alternative proposal would steer FRS away from this no-win situation.

Table 1 – Long Term Results of Different FRS Reform Options

Source: Pension Integrity Project actuarial forecast of FRS. The state is assumed to make 100 percent actuarially required contributions. Values are rounded and adjusted for inflation.

A Summary of Policy Suggestions

Florida policymakers are right to be concerned about the solvency of the state’s pension plan. However, simply closing the Florida Retirement System’s Pension Plan for future hires isn’t a complete solution. For Florida legislators seeking to implement meaningful pension reform next session, it is important that the state address the structural issues plaguing FRS in order to restore solvency and avoid making costly long-term mistakes. This means both tackling the still-growing debt of the defined benefit FRS Pension Plan and building a better-defined contribution FRS Investment Plan for current and future workers.

Next session, pension reform efforts should be centered upon the goals of all stakeholders. State policymakers can do this by considering the following:

- Reducing risk

- Close the existing FRS pension to new hires and offer a new FRS defined benefit pension option for new workers with the same level of benefits as the current plan, but with features to reduce long-term governmental risks and costs (e.g., 50/50 employer/employee cost sharing and a conservative investment return assumption).

- Gradually lower the assumed rate of return for the legacy plan to 6 percent.

- Reduce the amortization period to 20 years or less for legacy debt and to 15 years for new debt.

- Improving the defined contribution plan rates.

- Gradually increase both employer and employee contributions to the DC plan so contributions are above 10 percent of pay.

Conclusion

Florida’s policymakers, public workers, and taxpayers should seek to secure the Florida Retirement System so its ability to keep promises made to workers does not depend on everything going exactly as planned—a recipe that has not panned out over the last decade. The above analysis demonstrates the importance of testing any future potential reforms with an actuarial analysis that includes a variety of potential market outcomes, including those that fall below the plan’s expectations, a practice that is commonly known as stress testing.

There are various ways to achieve the legislative goals of eliminating or vastly reducing current and future public pension liabilities while improving the overall resilience of the Florida Retirement System. However, if Florida doesn’t address the rising debt within its defined benefit plan and continues to use insufficient contributions into the defined contribution plan, taxpayers will likely continue to be saddled with billions more in debt and the long-term retirement security of many public workers will be at risk.

The latest retirement reform effort fell short, both in the actual proposal and the ultimate legislative outcome. The good news is that state legislators do appear to be aware of the problem. Going forward, policymakers should try to foster a more collaborative process that involves as many stakeholders as possible, which will improve the chances of success in the end. To avoid perpetually growing public pension debt and costs, policymakers should also seek out a more comprehensive solution. Lastly, it is crucial to use actuarial analysis and stress testing to properly identify the changes that will effectively address all of the challenges FRS faces.

Originally published by Reason Foundation. Republished with permission.