By Colin Grabow

As millions of New Englanders brace for the coming winter chill and historically high energy prices, they might be interested to know that—per government emails obtained by the Cato Institute—at least one federal agency has been working with maritime industry lobbyists to deny them access to U.S. energy.

As Cato scholars have detailed, the Jones Act ensures that New England cannot access U.S. liquefied natural gas (LNG) and other energy products via tanker ships. For the same reason, hurricane‐hit Puerto Rico was recently forced to seek an emergency waiver of the 1920 law to obtain a limited quantity of U.S. LNG being stored in the neighboring Dominican Republic. Due to a total lack of LNG tankers that comply with the Jones Act, U.S. LNG can be sent to foreign countries but not domestic markets.

The denial of U.S.-origin energy to Americans due to protectionist maritime laws during times of crisis is troubling and farcical on its face. But the situation becomes downright scandalous when it’s revealed that a major impediment to relief is the U.S. Maritime Administration (MARAD), working hand in glove with (or for?) the domestic maritime industry.

For many months Cato Institute scholars have been sifting through thousands of pages of documents obtained from MARAD via the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA). As previously noted, one of these documents included a call for members of the Cato Institute to be charged with treason. But other things have been revealed as well.

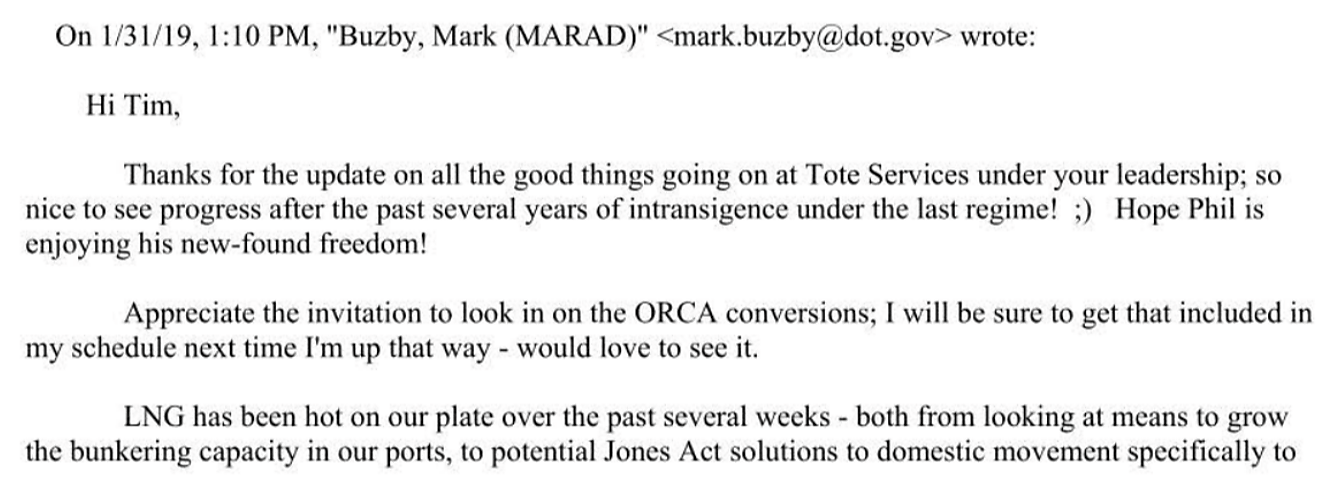

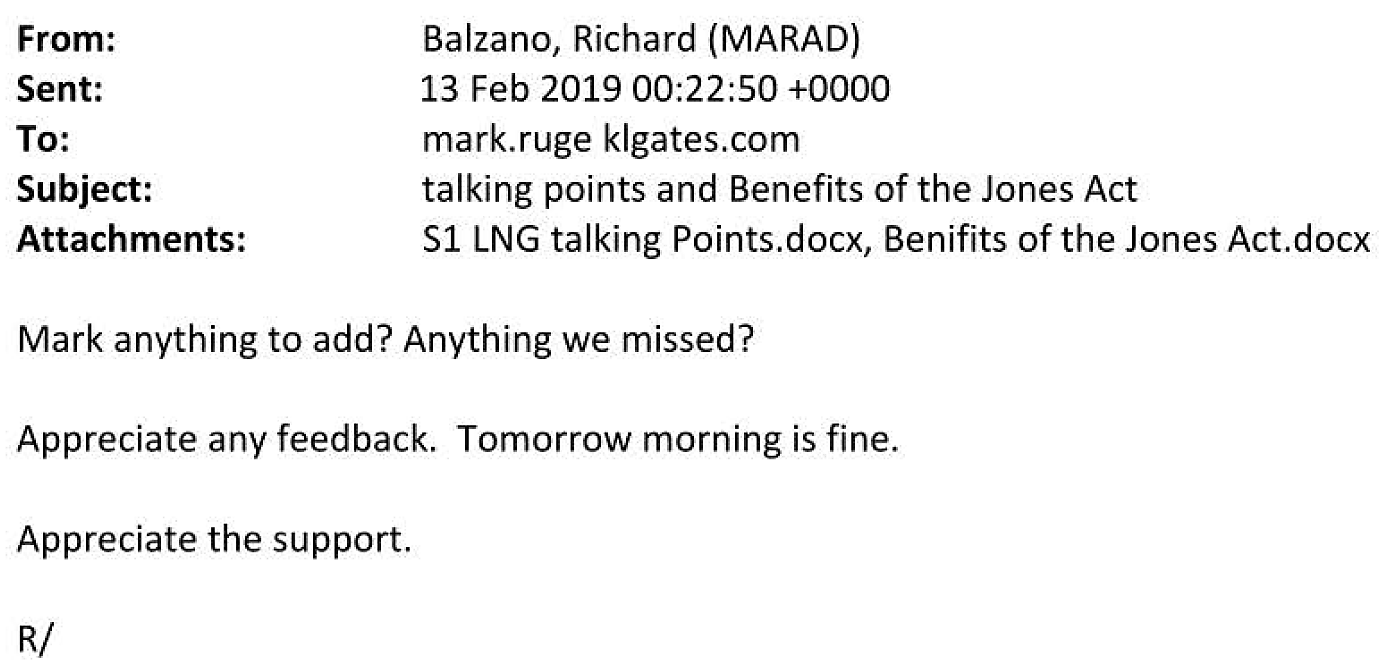

Among these are efforts by MARAD to thwart proposed waivers of the Jones Act during the Trump administration for the transportation of LNG. While the agency’s opposition does not surprise, the level of misinformation—if not outright dishonesty—is deeply concerning. These documents suggest that, at least in matters concerning the Jones Act, MARAD is properly regarded as a taxpayer‐funded lobbyist for the U.S. maritime industry.

Background: In early 2016 the United States began large‐scale exports of LNG following the opening of an export facility in Sabine Pass, Louisiana. As export levels increased, observers began to point out the Jones Act’s role in preventing this LNG from reaching U.S. consumers. In March 2018, for example, the Texas Railroad Commissioner sent an open letter to Congress noting the Northeast’s importation of gas from Russia instead of Texas because of the Jones Act. In August of that year, a group of New England governors floated the possibility of Jones Act modifications to help meet regional energy needs while that December Massachusetts released a comprehensive energy plan that repeatedly cited the Jones Act as an obstacle to obtaining domestic LNG.

Later that same month, Puerto Rico kicked the Jones Act hornet’s nest in earnest by requesting a ten‐year waiver of the law so that it could gain access to U.S. LNG.

With momentum for a Jones Act waiver building, MARAD swung into action. To wit:

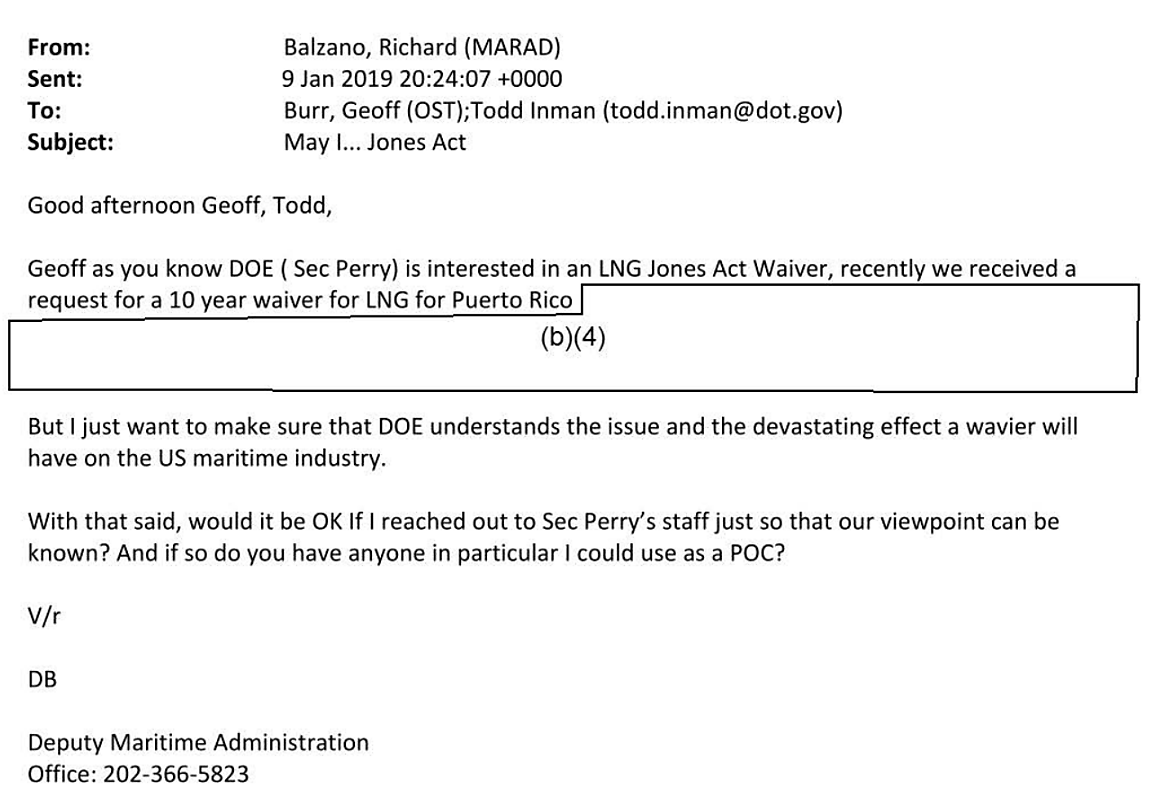

Email #1: Senior MARAD Official Attempts to Dissuade the Energy Department from Supporting a Jones Act Waiver: On January 9, 2019, MARAD Deputy Administrator Richard Balzano sent an email to two of Secretary of Transportation Elaine Chao’s top staffers, noting interest in a Jones Act waiver from Secretary of Energy Rick Perry. To head off this possible waiver, Balzano requested permission to reach out to Department of Energy officials to inform them of the alleged “devastating impact” it would have on the U.S. maritime industry. The claim is a curious one, particularly given that the entire rationale for such a waiver is that bulk transportation of LNG is not a service that the U.S. maritime industry provides.

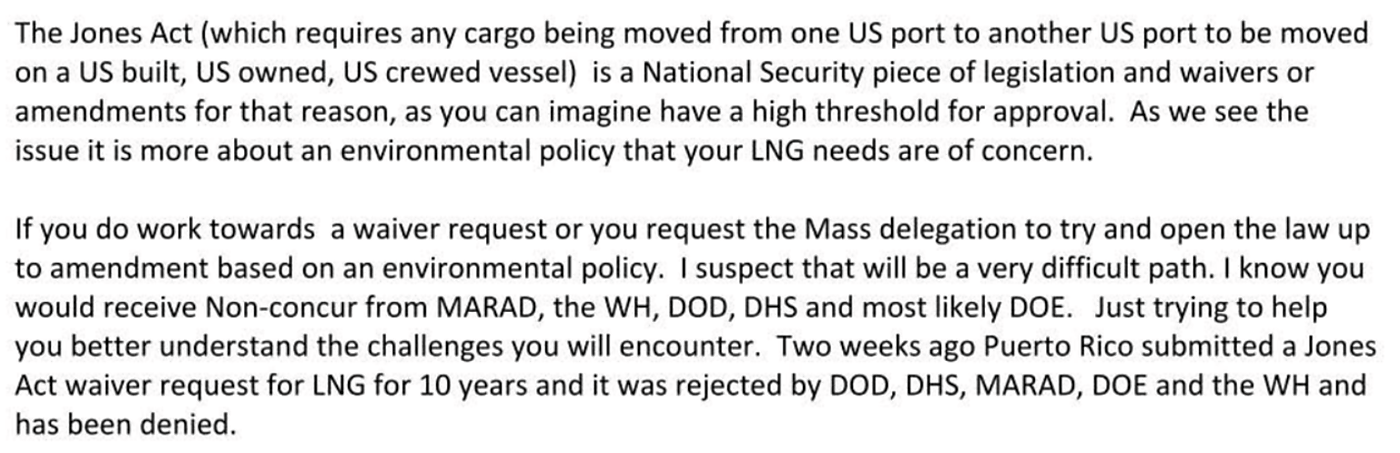

Email #2: Senior MARAD Official Misleads State Officials in Attempt to Discourage Pursuit of a Jones Act Waiver: Nine days later, Balzano emailed Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker’s director of federal‐state relations, the Massachusetts undersecretary of energy, and Exelon’s director of state government affairs in a clear attempt at discouraging them from pursuing a Jones Act waiver so that New England could obtain domestic LNG. Balzano stated that any such waiver would encounter “a very difficult path” with surefire opposition from the White House and Department of Defense among others, and the Department of Energy also likely to oppose. Balzano also claims that Puerto Rico’s waiver request made the previous month had already been widely rejected.

Statements about likely opposition from the Department of Energy conflict with Balzano’s email earlier that month noting Secretary Rick Perry’s interest in a Jones Act waiver. Talk of White House opposition, meanwhile, conflicts with the fact that senior White House staffers presented President Trump with a long‐term Jones Act waiver for LNG in April of that same year—a proposal Trump was said to initially support. Furthermore, the notion that Puerto Rico’s requested Jones Act waiver had already been rejected at this early date does not comport with the fact that a rejection letter was not sent until seven months later.

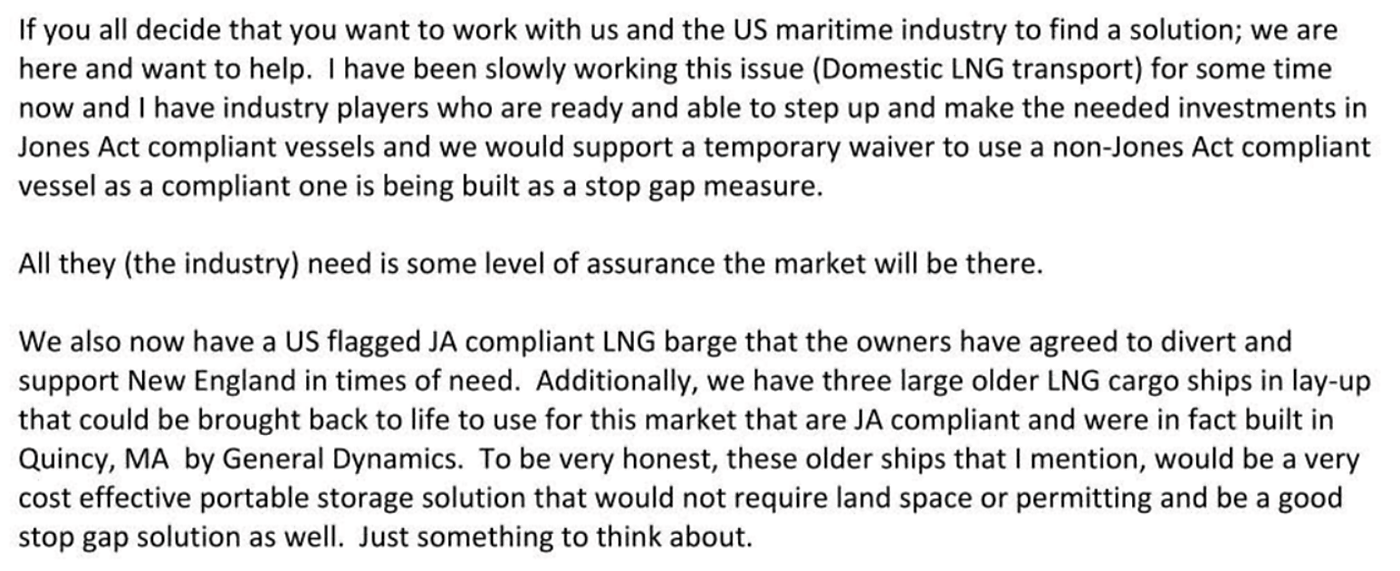

In the same email, meanwhile, Balzano also attempts to downplay the need for a waiver to meet New England’s LNG needs. Balzano noted the existence of a Jones Act‐compliant LNG barge whose owners “have agreed to divert and support New England in times of need” as well as some older LNG tankers that Balzano claims are Jones Act‐compliant.

Such talk is risible. The only vessel in existence at the time of Balzano’s email that matches his description is the Clean Jacksonville, a 2,200 cubic meter capacity bunkering barge used to refuel LNG‐powered ships. For perspective, a 2015 Government Accountability Office report notes that most modern tanker vessels used to transport LNG have a cargo volume of 160,000 to 170,000 cubic meters. In other words, the vessel offered by Balzano has a storage capacity less than 2 percent that of a typical LNG tanker and is thoroughly impractical as a solution to New England’s energy needs.

The three older LNG cargo ships cited by Balzano, meanwhile, appear to be a reference to the LNG Virgo, LNG Gemini, and LNG Leo. Built by a U.S. shipyard in the late 1970s, these ships became foreign‐flagged in the late 1990s and thus lost their ability to transport LNG within the United States. Legislation passed in 2011 allowed these ships to become re‐registered in the United States and gain Jones Act privileges provided their ownership did not change, but in 2017 exactly that happened when all three ships were sold to South Korean firm Sinokor. Thus, Balzano’s proposed use of ships exceeding 40 years of age as a stopgap solution wasn’t feasible even if there was interest in using the ancient vessels.

Eagle‐eyed observers, meanwhile, will note that the three ships are also mentioned in the same document calling for Cato Institute staff to be tried for treason (a proposed reflagging of these ships is the very next bullet point).

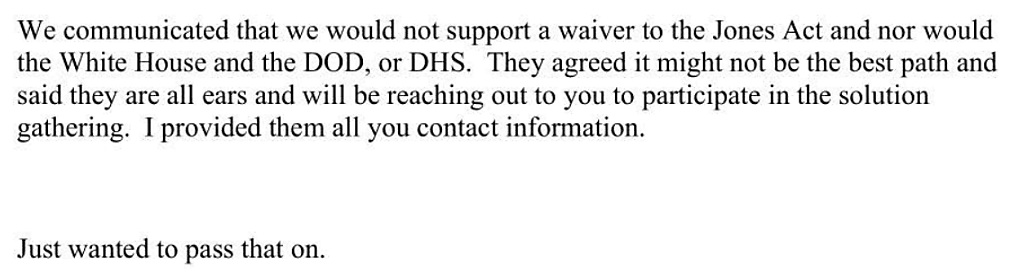

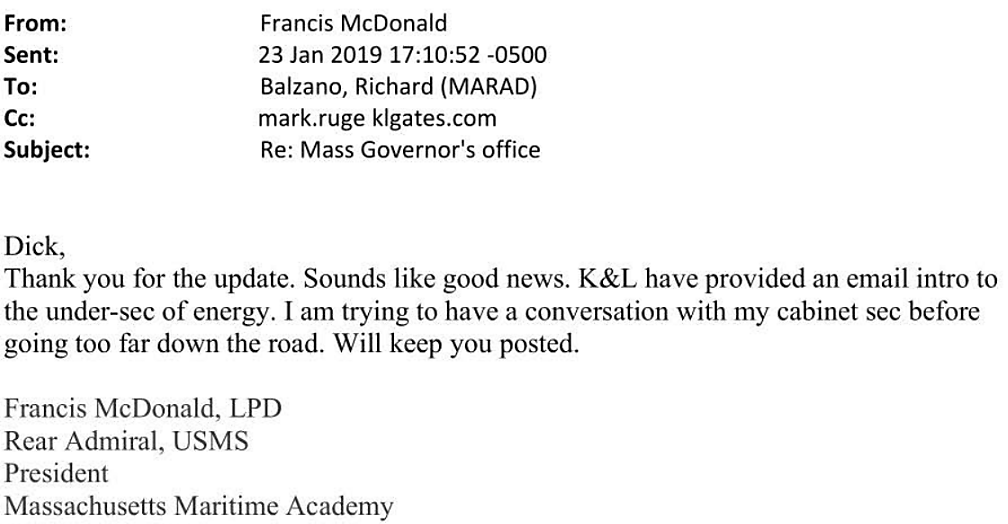

Email #3: Coordinated Efforts to Head Off a Waiver: In addition to his own efforts to halt a waiver, Balzano was also coordinating with the President of the Massachusetts Maritime Academy, Admiral Francis McDonald, to discourage Jones Act waiver efforts by Massachusetts state officials. On Jan. 23, 2019, Balzano emailed McDonald informing him that he told Massachusetts state officials “we would not support a waiver to the Jones Act and nor would the White House and the DOD, or DHS” and that he provided the officials with McDonald’s contact information.