Few mayors connect restrictive zoning to the growing problem of homelessness, a survey finds.

Restrictive codes can severely limit housing development, but a new survey of mayors finds that few take them into account in their plans to address homelessness.

Communities throughout the country are conducting Point-in-Time counts of the homeless this month, coming face-to-face with the realities of homelessness. According to a report released in December by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), nearly 600,000 Americans were homeless at this time last year.

HUD estimates that the total number of homeless increased only 0.3 percent between 2020 and 2022, but the chronic homeless population increased by about 15 percent during that time. More than half of the respondents to a May YouGov poll said that they knew someone — including themselves — who had been homeless, even if only briefly.

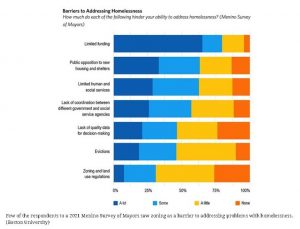

Last January the Boston University Initiative on Cities, drawing on data from the 2021 Menino Survey of Mayors, reported that only 1 in 5 mayors felt they had more than “moderate” control over homelessness in their cities. Six in 10 pointed to limited funding as the biggest barrier, and close to 7 in 10 had the view that zoning was a barrier of little or no consequence, despite the impact of zoning codes on housing development.

Source: Security.org

Get the data Created with Datawrapper

A new policy brief from the Initiative on Cities, developed in partnership with Cornell University and the nonprofit Community Solutions, examines the homelessness plans from America’s 100 largest cities. It found that just over half of the cities had a plan, and only 30 percent of those plans mentioned land use and zoning.

“A lot of public officials are not connecting macro-level housing market conditions with homelessness rates in their cities,” says Katherine Levine Einstein, co-principal investigator of the Menino Survey of Mayors.

Improving social services won’t be enough if housing is in short supply, or too expensive. Cities with the biggest homeless problems have the highest housing costs, says Einstein, who co-authored the brief with Cornell University researcher Charley E. Willison.

“Mental illness and drug addiction aren’t worse in San Francisco than they are in other American cities,” she says. “The problem is that housing costs are much higher.”

Mapping Zoning Challenges

It’s important to recognize that one of the basic reasons people don’t have housing is because the housing is not being built in the first place, says architect and attorney Sara Bronin. “A big reason for that is these misunderstood, often overlooked local zoning codes that have profound impacts on everything we do.”

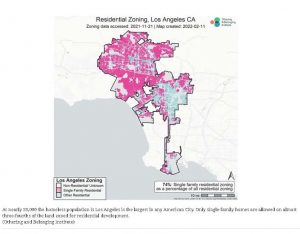

Bronin is the director and founder of the National Zoning Atlas, an effort to develop online, interactive maps that communicate essential aspects of zoning codes. Although restrictions on housing density have a well-recognized impact on housing development, code requirements regarding such things as lot size, parking spaces, building height or public hearings can also present barriers.

It’s not surprising that mayors might not have resources to look beyond single-family zoning rules and sort through such complexities.

Bronin, a Connecticut resident, led a team that included students, planners and a community foundation that collected codes from more than 2,600 jurisdictions in her state. They organized this into a data set, combined it with GIS maps and created the Connecticut Zoning Atlas, the first resource of its kind.

Similar efforts are now underway in 17 more states. The atlases that have been completed reveal zoning requirements that severely restrict housing production in cities, suburbs and rural areas alike, Bronin says.

“These arcane laws are constraining our ability to build the housing that people need and when we don’t build enough, prices rise and housing becomes less affordable.”

Even though a majority of mayors saw homelessness as something over which they did not have much control, local governments do have control over zoning and land use.

That’s not enough to reduce homelessness overnight, Einstein acknowledges. “But it could make a profound difference if we think about the trajectories of cities over 10 and 20 years.”

Hidden Actors

Community Solutions looked to the systemic, agile and data-based methods that the public health community has long employed to control diseases when developing its approach to ending homelessness. The disconnect between homelessness plans and land use polices is evidence of a “fragmented” response that is out of sync with the systemic thinking that it brings to communities in its network.

The zoning brief is the first product from a research collaboration between Community Solutions, Einstein and Willison. The three-year project will explore other “hidden actors” affecting homeless policy, says Zayba Abdulla, manager of state and local policy for Community Solutions.

The partners share an interest in identifying the ways that local governing structures themselves create obstacles to ending homelessness, says Einstein. “There are lots of government and nonprofit officials who have really good intentions, but they are often working at cross purposes.”

The next report will look at the extent to which local governments use law enforcement and sanitation agencies as first-line responses to homelessness. Almost 8 in 10 mayors in the 2021 Menino survey group said that homeless people faced more discrimination in their communities than Blacks, Latinos or transgender people, and 11 percent defined policy success as minimizing the impact of homelessness on businesses and residents.

Disrespect for the unsheltered is a barrier to progress, Einstein says. “It’s really hard to build a treatment facility or a homeless shelter, or even affordable housing, when we are dehumanizing the people who live in those places. People don’t like new development, period, even if it’s market rate.”

Local governments have more control over homelessness in their communities than responses to the Menino survey would suggest, Abdulla says. She is leading the development of a state playbook that will identify policy barriers, best practices, funding mechanisms, governance models, data-sharing agreements and policy remedies.

The First Step, Not the Only One

The omnibus spending bill passed at the end of 2022 includes $85 million for a “Yes In My Backyard” HUD grant program designed to incentivize zoning reform, and attention to zoning may be incorporated in guidelines for competitive federal infrastructure grants.

In 2020, amid pandemic concerns, the Government Accountability Office found a $100 increase in median household rent to be associated with a 9 percent increase in homeless rates. But homelessness has other dimensions, encompassing matters as wide-ranging as addiction, education, job training and health.

As important as removing barriers to housing development is, Einstein doesn’t discount the need to continue to pay attention to other aspects of the nation’s homelessness crisis. “I would hate for someone to take away from our report that if we just build more housing, homelessness will magically go down to zero.”

She suggests that a more centralized, integrated, even friendly approach to social service bureaucracies would be a big step forward. Many of the unhoused have had punitive interactions with the country’s welfare state and may be reluctant to work with government officials.

In addition to taking a more active role in increasing housing supply, local governments have many policy levers that can improve the economic well-being of community members and reduce their likelihood of ending up unhoused, says Einstein. “It would be great to see public officials do all of them.”

Originally published by Governing. Republished with permission.

For more great content from Budget & Tax News.