There is something bizarre about America’s presidential delegate selection process, with Iowa and New Hampshire dominating their first spots, columnist Michael Barone says

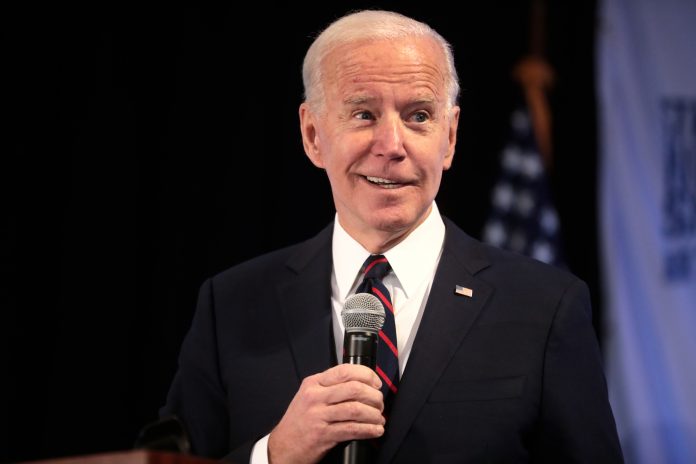

For a president who proclaimed proudly in his annual speech that his policies have made the state of the union good, Joe Biden betrayed a certain insecurity when, just two days before, he caused the Democratic National Committee to change its presidential primary schedule for 2024.

The reasons for Biden’s insecurity are obvious. Only 31% of self-identified Democrats want to renominate Biden for a second term as president, according to a Jan. 27-Feb. 1 Washington Post poll, while 58% would “like the Democratic party to nominate someone other than Biden.” That’s a weaker showing among Democratic voters than Lyndon Johnson’s in early 1968, two months before he dropped out of the race.

Under the DNC’s new rules, for the first time in 50 years, the party’s nomination race will no longer begin with the Iowa caucuses and the New Hampshire primary. In 2020, Biden finished fifth in those contests, with 15% and 8%, respectively. (Actually, there’s some question about the Iowa numbers since Iowa Democrats count not voters but “state convention delegate equivalents” and their computer counting process broke down.)

Now, Democrats say that South Carolina gets to vote first on Feb. 3. In that state last time, Biden won 49% of the vote in a 12-candidate field after an endorsement from the state’s lone black Democratic congressman, Rep. James Clyburn. Biden won 41 of 47 primaries and caucuses held after South Carolina.

For 2024, the rules allow New Hampshire and Nevada to vote three days later, on Feb. 6, to be followed perhaps by Georgia on Feb. 13 and Michigan on Feb. 27. Iowa, scorned for its counting fiasco, is not on the list.

The Democratic Party is the oldest political party in the world and has, from its beginnings, been a coalition of out-groups — people not considered typically American but who, when they hold together, can assemble a national majority. The primary schedule in the past has been refashioned to give one subgroup an advantage over others. Back in the Vietnam War years, for example, Iowa-born strategist Alan Baron pushed the state’s importance because of its historic pacifist and dovish tilt. New Hampshire Democrats, nervous about a planned nuclear plant, had been considered pro-environment.

The Biden reschedule gives primacy to black voters. In 2020, black people made up only 3% of Iowa Democratic caucusgoers and 3% of New Hampshire Democratic voters. But they were 56% of Democratic voters in South Carolina, and Biden won 61% of their votes. Georgia and Michigan’s 2020 Democratic primary electorates were 28% and 19% black, respectively.

The losing Democratic constituency from the Biden reshuffle is the gentry liberals, generally isolated as white college graduates. These days, they’re the leftmost Democratic constituency on many issues, less supportive of strengthening the military, reducing crime and reducing budget deficits, according to Pew Research.

In post-George Floyd Minneapolis, black people voted against and gentry liberals voted for defunding the police. “Black voters,” Clinton counselor Paul Begala tells the New York Times’ Thomas Edsall, “are the most loyal Democrats and the most sensible, practical, strategic and moderate voters.”

One potential candidate hurt by the Biden reshuffle is his 2020 rival and current Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg, who leads Biden in at least one New Hampshire poll. In 2020, “Mayor Pete,” as he was then called, ran close (no one knows exactly how close) to Bernie Sanders in Iowa and then lost to Sanders by 26% to 24% in New Hampshire. Exit polls showed him leading Sanders among white college grads in both states.

Black voters, however, have been less supportive of gay rights and unwilling to support openly gay candidates. One South Carolina poll had Buttigieg with 0% among black Democrats. Putting South Carolina first threatens to put the kibosh on a Buttigieg candidacy, to the extent that his performance at DOT — on paternity leave during the supply chain crisis, predicting smooth flying during the Christmas holiday — hasn’t already done so.

By the way, it’s not clear why Buttigieg, the former mayor of South Bend (population 103,000), Indiana, has been regarded as stronger presidential timber than Jared Polis, who is also gay, and who was just reelected as governor of Colorado (population 5,840,000) by a margin (20 points) comparable to Ron DeSantis’ in Florida, and larger than the margins of Democratic governors in California, New York and Illinois.

It’s also not clear that the DNC’s Biden schedule will actually happen. In the 1970s, the primary calendar was determined by Democrats because most states had Democratic legislatures. Today, however, most states don’t.

The DNC will probably prevent Iowa Democrats (but not Republicans) from holding a caucus. But New Hampshire’s Republican governor and legislature (and New Hampshire Democrats, too) want to keep their first-in-the-nation primary, and state law has commanded that it be held before any other state’s. (I’ve always wondered what would happen if another state passed a law scheduling its primary a week before New Hampshire’s.)

New Hampshire polls may not mind DNC penalties such as not seating their tiny number of delegates (32 out of 4,523, according to preliminary estimates), just as Michigan and Florida held earlier-than-permitted primaries in 2008 that threatened to cost them half their much larger delegations.

There is something bizarre about America’s presidential delegate selection process, about how Iowa and New Hampshire have monopolized their first spots for half a century as if they were enshrined in the Constitution, and about how those who have fiddled with the schedule have as often as not produced unintended consequences.

The Biden reshuffle is designed to produce a smooth path for his renomination. But what if, in Republican pre-South Carolina contests, Ron DeSantis (or someone else) knocks off Donald Trump, whom current polls show to be Biden’s weakest opponent and thus his best chance for reelection? Does some lone opponent then knock out Joe Biden, as Eugene McCarthy did Lyndon Johnson in 1968?

Of course, that may not happen — you might have a scenario that will. The lesson is that there’s no perfect way to pick presidential nominees, and most voters hope the nation does better than it has the last couple of times.

Michael Barone is a senior political analyst for the Washington Examiner, resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and longtime co-author of The Almanac of American Politics.

COPYRIGHT 2023 CREATORS.COM

For more Rights, Justice, and Culture News.

For more public policy from The Heartland Institute.