Life, Liberty, Property #18: GOP should hang tough regarding debt ceiling after passing the Limit, Save, Grow Act.

IN THIS ISSUE:

-

- GOP Should Hang Tough Regarding Debt Ceiling

- I Agree with The New York Times

- Cartoon

GOP Should Hang Tough Regarding Debt Ceiling

With negotiations having broken down regarding raising the debt ceiling, my advice to the Republican congressional leaders is this: hang tough.

With negotiations having broken down regarding raising the debt ceiling, my advice to the Republican congressional leaders is this: hang tough.

Do not give in. Concede nothing.

If that sounds harsh or risky, just look at the facts about federal government deficits and debt:

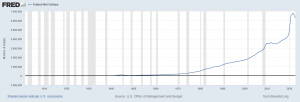

Total Federal Debt

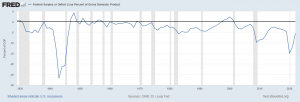

Federal Debt as a Percent of Gross Domestic Product

(Does not include entitlement promises.)

The issue is uncomplicated. The federal government spends far, far, far too much and has to stop:

Annual Federal Deficit (down is bad)

Annual Federal Deficit as a Percent of Gross Domestic Product

(down is bad)

Note this: none of this debt is attributable to Russia, COVID-19, 9-11, or any other crisis, real or imagined. Every bit of it is the result of chronic deficit spending allocated by Congress with the consent of presidents. Spending has trended steadily upward since the implementation and regular expansion of Great Society programs beginning in the 1960s:

U.S. Federal Government Spending: Budget Outlays

U.S. Federal Government Spending: Net Outlays

Ask yourself the simple, critical question: Did we really need to spend all that money and run up all that debt? In other words, would the nation have fallen apart had our federal government not borrowed all that money?

Would we have suffered an armed foreign invasion (as opposed to the largely unarmed immigration incursion of the past half-century). Would tens of millions of people have died from a bad case of the flu? Would states have imposed tariffs against one another and tanked the economy? Would there have been less “domestic tranquility”? (And would anyone but a barbarian describe our nation as having been tranquil for the past three-quarters of a century?) Would states have replaced their constitutionally mandated “republican form of government” with dictatorships? And if they had done so, would they have looked much different from what we suffered in 2020? Would the states have been unprotected against “domestic Violence”? And if so, would that have looked any different from the summer of 2020?

It’s a simple question. Are the present and future generations that are required to pay off that debt going to benefit from it? The very notion is absurd. Who, then, does benefit? Politicians and the greedy companies that lobby them are the obvious beneficiaries.

Nations run into problems all the time, and when things go wrong, good governments cut back on spending on things that are “wants” and not needs. The U.S. government has been buying votes from the public for decades, and each time this process becomes unsustainable—when the government hits its borrowing limit—the politicians band together to demand even more money.

Note that the rare, brief periods of budget surpluses in the two federal deficit graphs above coincide with Republican control of Congress, and in two of the three cases there was a Democrat president. Republicans become more courageous about the debt when they can use the issue to force concessions from a Democrat president or a weakened Republican president (such as George W. Bush), and the economy grows as a result—even when federal spending rises:

U.S. Real Gross Domestic Product per Capita

(See also the graphs of Annual Federal Deficit and Annual Federal Deficit as a Percent of Gross Domestic Product above.)

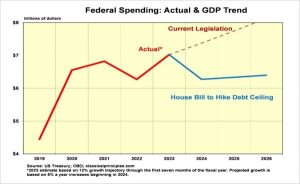

As economist Robert Genetski points out, the Republicans’ plan would do nothing radical, merely returning federal spending to its 2020 number and rising from there:

The media will continue to bury us with their typical avalanche of horror stories about “defaulting on the nation’s sovereign debt” and the catastrophe that will inevitably follow. As others have pointed out, however, there is no prospect of the nation defaulting on its debt unless President Joe Biden and Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen choose to do so for reasons unrelated to federal law, the Constitution, and the present circumstances.

As columnist Daniel Horowitz notes in The Blaze, there is definitely enough money to “pay our bills”:

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen wrongly asserted that if Congress fails to issue more debt authority immediately this month, “We have to default on some obligation, whether it’s Treasuries or payments to Social Security recipients.” That is simply a false statement, because we have enough revenue to cover three-quarters of what the feds what to fund.

Here’s the back-of-the-envelope math: The Treasury takes in enough revenue to account for about three-quarters of the $6.8 trillion budget Congress passed last year. In that sense the debt limit is an instant balanced budget, which some are estimating will begin to come due on June 15. We take in $4.8 trillion in revenue. Net interest on the debt is $663 billion. So as long as the government pays that interest, there is simply no default on the debt. Period. What about other payments? Here are some of the important ones:

Social Security: $1.3 trillion;

Medicare (net, minus offsets): $820 billion;

Defense: $800 billion;

Veterans’ programs: $173 billion.

The simple fact is that there is enough money to pay for these programs and interest on the debt, with roughly $1 trillion left to spare to focus on the core discretionary agencies and elements of Medicaid.

There would be details to be worked out, of course, to accommodate the variability of revenues and outlays, but that is a technical problem, not a reason to default on the debt. The Congressional Budget Office confirms that this is workable, CNBC reports:

The Congressional Budget Office on Friday said tax revenues and emergency measures after June 15 “will probably allow the government to continue financing operations through at least the end of July.”

The updated guidance otherwise reiterated the CBO’s earlier uncertainty about the debt ceiling during the first few weeks of June. Even though mid-June tax revenues could ease pressure on the Treasury through July, there’s still the risk of default in the first few weeks of June, the key government forecaster said.

Congressional Democrats and the Biden administration are all saying the Republicans must agree to a deal so that “we can pay our bills.” This Congress did not run up those bills. The Democrat-controlled Congress of 2021 and 2022—with razor-thin majorities—implemented all the new spending that has pushed the debt pile to the ceiling, and they frequently did so with no Republican votes at all. They ran up the bills and failed to provide a way to pay them. That is on them.

The Republicans should not bail them out. The Republican offer, the Limit, Save, and Grow Act of 2023, is quite generous enough. The Democrats get more money to spend than they had in 2019, and the American people get a limit on how quickly the federal budget grows, and perhaps even more importantly, a slowing of the metastatic growth of federal regulation.

If Biden and the congressional Democrats refuse that deal, the consequences are on them. With supreme arrogance, they ran up the bills and strangled, through overregulation, the American enterprises that pay for them. The Democrats didn’t make deals with Republicans when they did that. Republicans should not make any further deals with them now.

Sources: Federal Reserve Economic Data; The Epoch Times; The Blaze; CNBC

I Agree with The New York Times

It’s not often that I agree with The New York Times, but boy, when they’re right, they’re right.

The Republicans’ proposed debt ceiling plan—the Limit, Save, and Grow Act (LSGA) of 2023, “has mostly attracted attention for its part in the debate about raising the country’s borrowing limit and for its proposals to reduce federal deficits over the next decade,” the NYT writes. “But its effort to reshape the federal regulatory process could arguably have a deeper impact on the future functioning of government.”

I agree!

The Republican bill incorporates the REINS Act, “a legislative proposal designed to restrain the administrative state by amending the Congressional Review Act (CRA) of 1996,” as Ballotpedia describes it. The legislation, designed by then-Congressman Geoffrey Davis (R-KY), has been introduced in Congress seven times since 2011, and has regularly been passed by the U.S. House and stalled in the Senate.

The REINS (Regulations from the Executive in Need of Scrutiny) Act was designed to flip the script on federal regulation. The way things stand, and have done for decades, Congress passes extensive regulations on the American people and our businesses and other activities, and it leaves it to the executive branch to work out the details. The president’s cabinet departments and other federal government agencies then issue rules implementing the legislation after a period of public comments which the regulators are free to ignore.

Members of the public regularly take the government to court for the agencies’ often highly creative interpretations of Congress’ intent in writing regulatory statutes, with these agencies’ rules frequently involving much more government intrusion than one might have thought the text of the statute authorized. The courts generally accept the agencies’ decisions, under a principle called Chevron deference, after a 1984 Supreme Court decision.

That essentially means it is up to the public to prove executive branch agencies have overstepped their bounds, instead of the agencies having to prove their rules accurately reflect congressional intent. Agencies are essentially given the authority to make rules with the force of law, which is, of course, a legislative function, not an executive one.

The court decisions have afforded federal agencies vast authority to decide everything from how much water your washing machine can use to whether you are allowed to fill in a two-foot hole in the ground on your property.

The New York Times story says essentially the same thing, though its description makes the process sound rather more innocent and beneficial than what I wrote above:

While Congress passes laws every year, federal agencies tend to roll out many, many more regulations. Those long, often technical rules help business understand how the government works, by setting standards for allowable pollution, establishing how much doctors and hospitals will be paid for medical care, and explaining what numerous technical or vague terms and processes in legislation really mean.

We all know how much “long, often technical rules” imposed by other people usually “help” us. And, of course, we fully “understand how the government works” without any help from regulators: badly.

The premise behind this assumption of rulemaking accuracy is that if the wording of a statute is ambiguous or does not specifically forbid something some executive branch agency would like to do in an area covered by the legislation, the agencies, president, and courts will assume the proposed rule must have been A-OK with Congress or the legislature would have said so in the text of the statute.

The REINS Act would turn that around, requiring explicit congressional approval of any agency rule that would have a significant effect on the economy. Ballotpedia describes it as follows:

Under the CRA, Congress has the authority to issue resolutions of disapproval to nullify agency regulations. The REINS Act would broaden the CRA not only to allow Congress to issue resolutions of disapproval, but also to require congressional approval of certain major agency regulations before agencies could implement them. The REINS Act defines major agency regulations as those that have financial impacts on the U.S. economy of $100 million or more, increase consumer prices, or have significant harmful effects on the economy.

An expert quoted by The New York Times sees the proposed LSGA provision as an insurmountable impediment to agencies’ ability to create rules:

“The practical impact of this in a time of divided government like we have now is that I think no major rule would ever get done,” said Jonathan Siegel, a law professor at George Washington, who has written about the bill at length.

I am by no means convinced that no rules would be written “in a time of divided government,” but I certainly share Siegel’s dream.

As it happens, we have a divided government right now, and the NYT correctly observes that a single house of Congress could block a major rule imposed by the executive branch:

If the Republican House wanted to deny the Biden administration policy wins, it could simply vote no on every regulation it proposed. Those might include rules that explain how major portions of last year’s Inflation Reduction Act are meant to work. In a REINS Act world, the Republican House could just block those rules, effectively thwarting legislation passed by a previous Congress.

Now that sounds a bit churlish, voting down a regulation just because you “wanted to deny the Biden administration policy wins” and not because of a sincere opposition to the rule. However, the NYT is correct that a single house of Congress would be able to block rules. Once again, we are in sweet accord.

One of the experts quoted in the article characterizes the Biden administration as a “beast” and brings up the dirty word “nullified”:

“If you starve the beast by never allowing the implementing regulations to issue, then you have in effect nullified the legislation,” said Sally Katzen, a co-director of the legislative and regulatory process clinic at New York University who was the top regulatory official in the Clinton administration.

Starving a beast sounds like rather rough treatment, but since this is clearly a very bad beast, I’ll allow Katzen her metaphor and join in her sentiment in practical terms.

Katzen’s use of the word “nullified” is rather unfortunate, referring as it does to a highly controversial and much-criticized concept. The notion that states have the authority to nullify—to defy and render void—federal laws has long been derided. Katzen suggests that members of Congress would be doing the same thing if they voted to cancel executive branch interpretations of … the laws Congress passed. That seems rather different to me.

Expanding on the terrifying prospect that pesky Republican majorities in Congress could destroy the rule of law by cancelling ingenious executive branch reinterpretations of the laws the Republicans passed, the NYT quotes a law professor who knows just what’s going on here, by golly:

“What they want to do is to make it impossible to regulate,” said Nicholas Bagley, a law professor at the University of Michigan.

“Impossible to regulate”!

I wish I could share Bagley’s optimism about that, but I suspect that the great army of people in the federal government who love to jam spiky regulations into every nook and cranny of American life will find a way to deploy their talents occasionally. However, I do appreciate Bagley’s willingness to think big.

In a nation deeply divided by politics, it is heartening to find so much to agree with The New York Times on so important a subject as regulation. Perhaps there is hope for this nation after all.

Eh, probably not.

Sources: The New York Times; Ballotpedia; Cornell Law School Legal Information Institute

Cartoon

via Townhall

For past issues of LLP.