Budget cuts will affect the national security functions of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), says CDC Director Mandy Cohen.

The CDC’s spending was cut to pre-pandemic levels in the congressional debt-ceiling deal. The CDC had a budget of $9 billion and a workforce of 15,000 employees in 2020.

The CDC needs more funding, Cohen told National Public Radio in an interview on August 1.

“The CDC is an important national security asset,” Cohen. “I think we understand that in a different way than ever before. We need to have a strong asset that can identify threats and respond to them quickly so that we can protect everyone’s health. … Cuts are not going to allow us to do it. In fact, we need the right investments to make sure we have the data infrastructure and the workforce needed to be that national security asset that the country deserves.”

The cuts to the CDC’s budget were made after widespread criticism of the agency for its response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Mission Creep

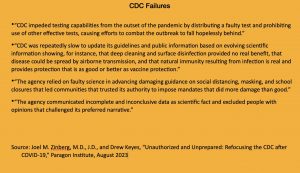

The CDC has strayed from its primary function, says a report titled “Unauthorized and Unprepared: Refocusing the CDC after COVID-19,” by Joel M. Zinberg, M.D., J.D., director of the Public Health and American Well-Being Initiative at the Paragon Health Institute (PHI) and a senior fellow at the Competitive Enterprise Institute (CEI ) and Drew Keyes, a senior policy analyst with PHI.

“The CDC’s failures during the pandemic undermined public trust,” states the report. “Unless the CDC is reformed and refocused on its core mission it will be unprepared to act effectively in future pandemics which will surely come.”

The CDC has expanded far beyond its basic purpose, according to Zinberg and Keyes.

“After reviewing the history, organization, and pandemic performance of the CDC, we identify the basic problem as mission creep, abetted by the lack of congressional authorization for the agency,” Zinberg and Keyes write. “The CDC has grown into a large, diffuse agency with priorities that are far afield from its core mission of controlling and preventing communicable disease outbreaks. The profusion of programs left the agency unprepared for the pandemic and distracted it from an effective response.”

The Communicable Disease Center, as the CDC was originally known, was created on July 1, 1946, through executive action, rather than legislation, and started with a budget of $10 million and fewer than 400 employees.

Applied Science

The CDC’s original mission was “to diagnose and control communicable diseases through the application of epidemiological science and, with that goal in mind, to serve the states with ‘training, investigations, and control technology’ and surveillance of disease-related threats,” states the report.

Successes in responding to malaria, polio, and several pandemics, along with its role in the eradication of smallpox, boosted the agency’s reputation.

The agency’s expansion beyond its original mission was made possible by the absence of statutory guardrails from Congress, say Zinberg and Keyes.

“The lack of direct congressional authorization, aggressive efforts by the CDC’s early directors to expand the agency’s purview, and the willingness of executive branch officials to delegate authority to CDC led to a rapid expansion of the agency’s responsibilities beyond its original mission of dealing with communicable diseases,” write Zinberg and Keyes.

Agency Has Multiple Priorities

Unfettered by congressional restraints, the CDC “grew by acquisition,” adding programs in communicable and non-communicable disease areas alike, Zinberg and Keyes write.

“CDC priorities now include addressing ‘the public health consequences of the climate crisis,’ reducing racial disparities in public health,’ addressing ‘the social determinants of health conditions in the places where people live, learn, work, and play’ and ‘increases in injury and violence prevention programs that will help to address the growing crisis of domestic, sexual, and gun violence,’” states the report.

The overextended agency made numerous missteps during the pandemic, but money wasn’t an issue, states the report.

“We cannot rely on the CDC to reform itself,” write Zinberg and Keyes. “[L]ack of focus and incompetent performance, not inadequate funding, were the causes of the CDC’s pandemic failures.”

Congressional Action Needed

The remedy for the CDC’s failures is legislative, says the report.

“Congress must engage in the hard work of outlining exactly what activities the CDC should and should not undertake,” write Zinberg and Keyes. “It should undertake a comprehensive, center-by-center authorization of the CDC.”

The CDC has pursued an ever-widening agenda, while public health has declined, says Katy Talento, CEO of AllBetter Health and a former health adviser to President Trump.

“The CDC has failed America in every way,” said Talento. “Its core competency was supposed to be infectious disease, and it has irreversibly lost the faith of the American people, who refuse to take its recommendations seriously anymore. Rather than focusing on that one job well, the CDC has expanded into unaccountable grantmaking and programs for chronic conditions. On that front, Americans—especially children—have grown exponentially sicker on its watch, including from Type II diabetes, obesity, autism, and allergies.”

Overbearing policies during the pandemic raised public awareness, says Marilyn Singleton, M.D, J.D.

“I like to point out that there were good things that came out of the COVID debacle,” said Singleton. “It opened everyone’s eyes to the consequences of a sprawling government with unbridled power and passive acceptance of incompetence with no accountability. The CDC has become, as the adage goes, a jack-of-all-trades and a master of none.”

Bonner Russell Cohen, Ph.D. (bcohen@nationalcenter.org) is a senior fellow at the National Center for Public Policy Research.