Life, Liberty, Property #51: fiscal conservatives can win the budget war by sticking with a continuing resolution that cuts spending.

by S.T. Karnick

IN THIS ISSUE:

- Fiscal Conservatives Can Win the Budget War

- De-Accredit Higher Education

- Raising Keynes

- Bud Light Sales Spillage

- Cartoon

SUBSCRIBE to Life, Liberty & Property (it’s free). Read previous issues.

Fiscal Conservatives Can Win the Budget War

Fiscal Conservatives Can Win the Budget War

The Uniparty in Congress is once again engaged in its recurring haggling over how to avoid a government shutdown, with the next deadline set to arrive in a matter of days. Everybody says the House Republicans must lead on the process.

I suggest that the Republicans do just that: lead. It will take some nerve, something congressional Republicans almost never show.

Note that government shutdowns always loom, and ominously. They never arise on the horizon like the beautiful, hopeful sunrise that they really signify. Just imagine a smaller, less intrusive federal government doing less economic and social damage! The heart sings at the prospect.

The possible scenarios for avoiding a beautiful shutdown are an agreement on a complete budget (highly unlikely because this is Congress, after all), no deal and a shutdown (highly unlikely because perceived as politically damaging by Republicans), a last-minute omnibus bill (unlikely because it would involve a whole lot more work pronto, plus many Republicans know it would be horrendous), or a continuing resolution to keep the government going for some specified span of time (a possibility because the other options are pretty much out of the running for the reasons noted).

The conservative Freedom Caucus in Congress has long been pushing for a return to regular order, in which Congress votes on 12 annual appropriations bills, with each standing or falling on its own merits. The present Congress has passed seven of the proposed appropriations bills, and five of those are set to expire on March 1. By my math, that means the House and Senate would have to agree on 10 appropriations bills within the next couple of weeks.

The only way that will happen is for Republicans to give President Joe Biden and the Senate Democrats all or nearly all that they want.

OK, that definitely could happen.

The Freedom Caucus has now changed course and is supporting a continuing resolution. As Reason magazine reporter Eric Boehm notes, that would establish an actual budget cut:

As part of the deal to raise the debt limit last year, hardline conservatives successfully included a provision that would implement an automatic, across-the-board 1 percent spending cut for the entire government on April 30—unless all 12 appropriations bills are passed by that deadline.

I use the redundant word “actual” because it is such an amazing idea. A federal budget cut, however small, is an extraordinary thing to contemplate.

Of course, the Democrats will never stand for that, and the reversion to a continuing resolution approach would be a resumption of “the bad budget-making practices that have buried the government in debt,” as Boehm notes.

A budget cut is a budget cut, however, so how about the congressional Republicans finally show some smarts—and guts—and invite the Democrats to throw them into that thar briar patch? As the Committee to Unleash Prosperity notes, Republicans would be averting a supposed disaster and the Democrats would be the ones shutting down the government, all for a piddling 1 percent of a budget the American public already knows to be grotesquely bloated and corrupt:

Republicans should bring a clean continuing resolution on the floor, any Democrat voting against it would have to explain to the American people why they prefer a shutdown to a minuscule 1% cut to a budget even after they’ve added some $5 trillion of new spending under Biden.

On the budget stalemate, Republicans may have flipped the table on the Democrats. They should take their case to voters: Democrats are so addicted to debt spending that they won’t even accept a teeny weeny cut of less [than] $50 billion out of a $6 trillion annual budget.

I have a better idea for the Republicans—and for America. Bring to the floor a bill to restore federal government spending to its 2019, pre-pandemic level.

In the fourth quarter of 2023, the federal government spent about $6.4 trillion. In Q4 of 2019, the government spent approximately $4.8 trillion.

Offer $4.8 trillion for the next fiscal year. Propose cuts of $1.6 trillion from defense, food stamps, welfare and social spending, the Medicaid expansion (cap spending on it), and the like. Whatever it takes.

Then, let the Democrats complain about that as much as they like. Keep pointing out that in 2019 the nation was doing quite well, the economy was growing, and income equality among the major ethnic groups was shrinking. Stick to that.

Republicans, in this scenario, do not answer any other questions or discuss any specific claims of expected disasters from the cuts. They do not try to refute any sob stories of individual and group victims of the “cruel,” “draconian,” “reckless” budget cuts. Republicans just keep saying that the nation was at its recent peak of economic success with the 2019 budget and they only want to return us to those fine, sunny days of normal ravenous federal government greed and overreach relatively sensible federal spending.

Meanwhile, continually remind people that the Democrats are threatening a government shutdown. Stress the fact Democrats are objecting to a 1 percent reduction of the irresponsibly rapid growth of federal spending under President Joe Biden.

At the last moment, when everybody is sweating profusely over the coming shutdown catastrophe, Republicans should again offer the continuing resolution with the automatic, across-the-board 1 percent spending cut, and vote for it if the Democrats agree to the deal.

That’s a major change of strategy, in which the Republicans play the game the way the Democrats do: to win. Ask for what you really want, and then accept only the very best you can get.

That leaves only one question. Do the Republicans really want a less-disastrous federal budget?

Sources: The Washington Examiner; The Wall Street Journal; Reason; Committee to Unleash Prosperity

De-Accredit Higher Education

De-Accredit Higher Education

The current state of higher education is appalling. There is no mystery about that. The college degree has become nothing more than a decreasingly valued verification of white-collar employability, and students and faculty alike treat that credential as the worthless thing it is. Instead of pursuing academic excellence, students, faculty, and administrators have transformed college campuses into expensive pleasure palaces paid for by loans that students are increasingly invited to see as grants. Free inquiry is quashed, and agreement with political, sexual, and racial prejudices is mandatory.

Employers do precious little to call for greater attention to the ostensible (though corrupted) purpose of these institutions: the development of more-efficient white-collar human robots. Instead, employers adopt the corrupt regime of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) that is brutally enforced throughout higher education. (Support for this system has begun to erode in recent weeks in reaction to state laws limiting DEI and the revelations of open antisemitism on college campuses since last autumn. Those sentiments were rising for years but went largely unnoticed until the antisemites went on the march to take the side of Hamas against Israel last fall.)

My assessment is that the nation’s higher-education system is collapsing because of a steadily and rapidly increasing lack of market discipline over the past several decades. A full disintegration may be inevitable at this point, with the dissolution of the current system making way for the building of a new one upon its ashes. I think that to be the most likely scenario, and I feel no pity whatsoever for those who supported this system and benefited from it.

There remain, however, some analysts who think that extensive and deep reforms can save the system. A possible reform that has been floated from time to time is accreditation reform.

Author and professor Philip Jenkins noted in 2017 that both public and private institutions can be held accountable through accreditation:

Unknown to most non-academics, there is in fact a deterrent of nuclear proportions that can be invoked in circumstances of extreme and egregious misbehavior. So fearsome is this weapon that, if deployed, it would assuredly induce academic authorities to clean up their act. If you are not an academic administrator, you know next to nothing about accreditation. If however you are, even invoking that unspeakable thirteen letter word causes grown adults to blanch. American universities rely on public ignorance of that fact.

… All academic institutions, public and private, are accredited by various private agencies, which vouch for the quality and effectiveness of schools and their programs. Accreditation can be granted to a whole institution, or to specific programs that it offers.

The accreditation system is basically an oligopoly, Jenkins notes:

Dozens of such agencies exist, and they differ greatly in how far they acknowledge each other’s authority. There is, though, a core of six regional bodies that really matter. These include the Northwest Commission on Colleges and Universities (NWCCU), and the Middle States Commission on Higher Education (MSCHE). The NWCCU, for instance, accredits 159 universities and colleges, including Evergreen State; Middlebury is accredited by the New England Association of Schools and Colleges (NEASC).

Each of these agencies promulgates elaborate and quite draconian policies, covering minutiae of administrative policies, faculty qualifications, student support services, and student life. The language is expansive and designed to be legally enforceable. Institutions are reviewed regularly for compliance, and unadvertised visits and spot checks are a real possibility.

The accreditors hold an enormous amount of power, Jenkins observes:

Any institution or program found in violation of any part of these requirements is in deep trouble. Accreditation can be suspended, or schools can be reduced to probationary status during investigations, which are extremely long, expensive and time consuming. Literally, they can tie up a school and all its bureaucrats for years at a time. The ultimate nightmare is that a college can entirely lose its accredited status.

So, all we gotta do is get the accreditors on our side. That seems to me to be an exceedingly ambitious proposal. Jenkins suggests we put pressure on them, “whether from the U.S. administration, from legislators, or the general public. Make them do their job.”

I reckon that only legislative pressure can accomplish what Jenkins envisions. Certainly the federal government has a big potential influence, given that removal of accreditation would make an institution ineligible for all the goodies the government provides.

The federal government, however, is at least as corrupt as the higher-education system, regardless of which party is ostensibly in power. I surmise that the best we can hope for is a temporary lull in the present corruption if a determined president takes office accompanied by a hard-right Congress. How likely is that?

Novelist, playwright, and social analyst Jonathan Leaf suggests a different approach, via his own version of a “replacement theory,” writing at Law & Liberty:

[T]here is an answer to this wholesale problem: de-accreditation. America has been permitting academics to win one another’s favor by giving them the exclusive right to determine what programs are and aren’t meeting standards. This is akin to asking reality show contestants to define modesty.

It doesn’t have to be like this. There are serious groups, like the Intercollegiate Studies Institute (ISI), that offer regular reports on what’s happening in academia. If a rich donor is willing to supply the funding, they should do more than just assess college and university departments for their intellectual diversity, academic standards, and rates of employment for graduates. Those that don’t measure up should be given failing marks. ISI and groups like it could simply say that the departments are not, by their measure, accredited.

As Jenkins noted, de-accreditation has consequences that these institutions cannot ignore—but only if the government stands behind the new accreditation organizations, which is exceedingly unlikely at present and will remain so. There is, however, another element to the equation, Leaf writes:

Initially, some schools or departments that are de-accredited will likely bask pridefully in their censure. But I doubt this will last long. Academics are easily embarrassed. They won’t like those annual press reports saying that they have failed to provide their students with proper instruction or work opportunities. The enormous negative press coverage given to Penn, Harvard, and MIT over their college presidents’ congressional testimony on campus antisemitism has affected donations and admissions, and it’s apparent that much of the faculty at these schools would rather not be associated with the damning commentary. A list of such failing schools would be bound to act in the same way and give undergraduate and graduate applicants pause.

Leaf’s approach would deploy new accreditation institutions to impose market discipline on higher-education institutions through purely voluntary, nongovernmental means. That is a highly appealing premise.

If new accreditation institutions could show some success and credibility in evaluating higher-education programs, there might be something for a future presidential administration and Congress to rely on in introducing reforms at the federal level, Leaf writes:

There’s something more to think of, too. The Department of Education has been rubber-stamping the claims of the academic cliques about what trendy programs are and aren’t worthy of accreditation. Yet a future presidential administration could instead turn towards these independent reports. How would my alma mater, Yale, feel if its English department lost federal accreditation because it doesn’t require its doctoral students to read Shakespeare, Tennyson, or Twain? I have a fair degree of confidence that the mix of shame and trepidations regarding lost grant money would get its attention.

And, if conservatives really wanted to get frisky, they could make the Department of Education require the implementation of campus Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion programs on the basis of ideology. Or is that just a bit too ironic?

This seems to me a reasonable and principled way of approaching the dream of accreditation reform.

My preferred solution to the problems with our higher-education system is to starve the monster. Remove all federal government support of higher-education institutions currently done through student grants, student loan guarantees, direct grants to these establishments, the largely tax-free status of their gigantic endowments, favorable regulatory treatment, and other advantages currently lavished on them.

That would reintroduce a degree of market discipline and institutions’ accountability to the consumers of college degrees—the students, their parents, and employers. If states want to support higher education, they should be free to do so. The massive federal apparatus has corrupted higher education, and I believe that the system will continue to deteriorate until that is removed. As The Heartland Institute noted more than a dozen years ago, reform has long been urgently needed:

American higher education suffers from rapidly escalating costs and poor student learning outcomes. Collectively, the United States spends $430 billion on higher education, the equivalent of 3 percent of total gross domestic product (GDP), an amount that exceeds the entire GDPs of several midsize European countries.

Yet, there is growing evidence that students at campuses across America are not succeeding. Nearly 40 percent of students fail to graduate with a bachelor’s degree within six years of first enrolling in college, and data suggest even those who do graduate often have trouble finding college-level employment.

With high costs and frightening outcomes, it is clear American higher education needs serious reform.

The Heartland study referenced above called for accreditation reform:

Reduce Barriers to Entry and Encourage Accreditation Reform.

The cost of meeting accreditation standards is often very high, measured in millions of dollars. Yet, accreditation tends to be based on inputs—spending money—instead of outputs, the demonstrated proof that students are actually receiving a beneficial education. Reforming the accreditation system would allow more competitors to enter the higher education market and encourage institutions to compete based on cost and the value-added of their degrees.

Leaf’s proposal could provide a critical component of Heartland’s ten-point plan to rescue higher education in the United States.

American higher education has only gotten worse since 2011. Is it too late to save the system? Maybe—but it’s worth a try.

The critical remaining question is whether anybody has the courage to attempt it.

Sources: Law & Liberty; The American Conservative; The Heartland Institute

Raising Keynes

Raising Keynes

In reviewing the current federal budget negotiations, I ran across the following sentence in a Wall Street Journal news story on the federal debt: “Policy hawks often promote austerity as a remedy, but reductions in government spending can hit jobs and slow growth.”

That sentence and the discussion that followed seemed to me to be pure Keynesianism—specifically, the premise that government spending can expand the economy by raising aggregate demand. If anything in this great cosmos has been disproven conclusively, it is Keynesian economics.

The story goes on to elaborate on the presumed danger of federal budget cuts:

Even in the event tighter fiscal policy is enacted, if it helped usher in a recession, automatic stabilizers would kick in and tax revenues would fall. The upshot: a bigger deficit.

“When you have substantial reduction in deficit spending—whether by raising taxes substantially or cutting spending—there’s an excellent chance you help precipitate a recession,” said [Hartford Funds fixed-income strategist Amar] Reganti. “It becomes a vicious cycle.”

Source: The Wall Street Journal

Here we have The Wall Street Journal arguing that reducing the federal budget deficit is a bad thing.

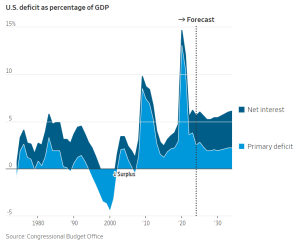

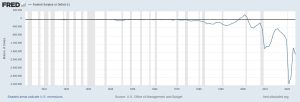

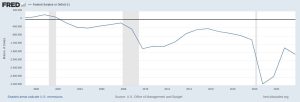

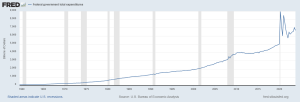

Here’s what the federal budget versus revenues looks like since the beginning of the previous century:

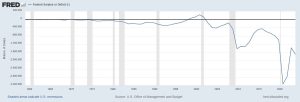

Source for these four graphs: St. Louis Fed

To home in on the relevant current situation, here’s what the past quarter-century looks like:

These deficits are all, always, caused by excessive federal spending (not tax rate reductions), as is evident by comparing the following graph with the above graphs for the same time period:

These deficits are all, always, caused by excessive federal spending (not tax rate reductions), as is evident by comparing the following graph with the above graphs for the same time period:

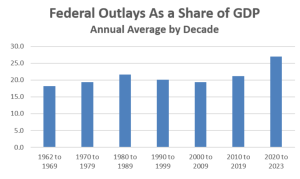

This graph from the Committee to Unleash Prosperity illustrates the ever-greater share of the U.S. economy the national government has gobbled up in the 2000s:

This graph from the Committee to Unleash Prosperity illustrates the ever-greater share of the U.S. economy the national government has gobbled up in the 2000s:

The implication that a 1 percent reduction in that regime of disastrous fiscal incontinence would risk tanking the economy is at best preposterous.

Thinking I must be missing some genius subtlety here, I asked some economist friends for their opinions.

Economic historian Brian Domitrovic of the Laffer Center said, “When government spending falls, [as in] the 1990s, the economy does great. Government spending gobbles up capital and labor that if left alone and facing low tax rates will bring growth.”

Economist and Heartland Daily News columnist Robert Genetski said, “Yes, it’s simple Keynesianism. My book Rich Nation/Poor Nation goes through the history of the United States since 1900. The case is clear: we should never look at the deficit to tell us anything about stimulus or restraint. We should look at spending and tax burdens as having a very different impact on the economy.

“On balance, federal spending growing faster than the rest of the economy weakens the economy and is characteristic of each period of progressive policies since the Wilson years in 1913,” Genetski said. “Increases in tax burdens are another characteristic of progressive economic policies. This combination explains every period of economic malaise or outright depression the United States has ever experienced. Our economic progress stopped whenever we adopted such policies. The opposite combination—federal spending growing slower than spending in the rest of the economy and lower tax burdens—created the booming economies of the 1920s, 1950s, and the Reagan years.”

Political scientist and economist Donald Devine, who served as director of the U.S. Office of Personnel Management under President Ronald Reagan, said, “I read that article at the time, and it is so wrong it is difficult to respond to.”

Devine waded in anyway: “The author backs into the truth by writing that cutting current spending to any politically possible level would not have much effect. Rather than [Treasury bonds] being ‘auctioned’ as the author suggests, there is an iceberg kept at the Fed from past spending, mostly unreported in interior ‘bonds.’ Compared to this, current cuts would be minor. And the author’s so-called ‘automatic stabilizers’ simply do not exist. His resulting ‘vicious cycle’ is much more the result of what is hidden in the Fed books than current spending, although of course more spending makes it worse. I don’t see how recession can be avoided.”

As these economists all note, we had best leave Keynes’ theories a-moldering in their grave.

Source: The Wall Street Journal

Bud Light Sales Spillage

Bud Light Sales Spillage

Bud Light beer sales spillage continues. The Epoch Times reports:

While Super Bowl Sunday beer sales jumped overall, Bud Light saw sales drop by about half, according to an analytics firm.

Beer drinkers apparently still are boycotting the brand months after it became embroiled in a controversy involving a transgender social media influencer.

The controversy, as you probably know, involved Bud Light engaging said influencer to endorse the beer. Bud Light’s main consumers, normal people whom the parent company’s executives openly disdained, responded with a boycott.

Before going woke, Bud Light was the number one choice for Super Bowl beer consumption, the story notes: “In 2023, Bud Light was the top-selling brand during the Super Bowl, the report noted. But during 2024’s game day, the brand had a sales drop of 50 percent.” Corona beer took the trophy this year, with Michelob Ultra also selling strongly.

This is good news for those who dislike the woke revolution, which many gigantic multinational corporations have joined enthusiastically in the past few years. The only way to get these powerful companies to listen to their customers is to make them suffer consequences—and those efforts must be sustained over time lest the companies simply factor in a short-term sales loss and consider it a reasonable price to pay.

With Bud Light giving more than $100 million to the anti-wokism UFC mixed martial arts series and paying former NFL players Peyton Manning and Emmit Smith to pretend to throw cans of Bud Light to bar patrons, we’re happy to let those people bathe in Anheuser-Busch’s money.

It will be doubly enjoyable to watch Bud Light fund the conservative-friendly UFC while enduring ever-greater losses in beer sales. Those who oppose corporate support of wokism must keep up the heat on these companies.

Source: The Epoch Times

Cartoon