The Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) is based on an important principle: any document that the public pays for belongs to the public. Whenever a government official writes or records something as part of their taxpayer-funded duties, ordinary citizens have a right to request a copy, with some exemptions for privacy and security.

Politicians, of course, hate that kind of accountability. And every so often, they get caught hiding their official correspondence from FOIA requesters. Hillary Clinton’s attempts to stash State Department emails on a private server were a major scandal during the 2016 election. Last week, FOIA became a part of the controversy surrounding coronavirus origins.

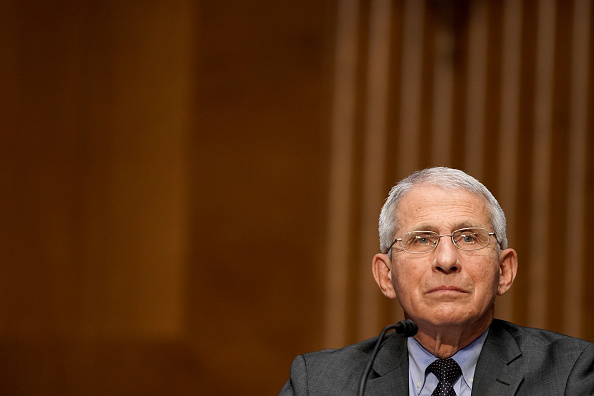

In emails uncovered by the House Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Pandemic last week, government scientist David Morens apparently plotted with a FOIA officer at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) on how to hide his emails. Morens, an adviser to former NIH official and White House Coronavirus Task Force member Anthony Fauci, wrote in February 2021 that “i learned from our foia lady here how to make emails disappear after i am foia’d but before the search starts. Plus i deleted most of those earlier emails after sending them to gmail.”

Elsewhere in the emails, he named the source of advice as “an old friend, Marg Moore, who heads our FOIA office and also hates FOIAs.”

Intentionally destroying or removing government records is very illegal, and there’s no magic grace period while a FOIA request is being processed. At a Thursday hearing, Morens told the House subcommittee that he was “not aware that anything I deleted, like emails, was a federal record” because his workplace FOIA training had “defined a federal record in a very different way than you may be thinking of it. None of it defined it as an email.”

The Department of Health and Human Services, which oversees the NIH, told The Nation that it “is committed to the letter and spirit of the Freedom of Information Act and adherence to Federal records management requirements. It is HHS policy that all personnel conducting business for, and on behalf of, HHS refrain from using personal email accounts to conduct HHS business.”

To be fair, it seems that Morens was really getting bad, almost superstitious FOIA advice from his colleagues. According to another November 2021 email, Morens was under the impression that some “ant-hacking” (anti-hacking?) software installed by his IT staff would make his Gmail account “safe from FOIA and hacking on all of my devices, including government computer and phone, and my private computer and iPad.”

Subcommittee chairman Rep. Brad Wenstrup (R–Ohio) also claims to have evidence suggesting that NIH officials purposely misspelled words to hide from FOIA requests. When members of the public request all documents on a certain topic, FOIA officers often ask them for specific keywords to search, so misspelling important names could keep a message out of the search results.

It isn’t the first time the House subcommittee caught Morens trying to get around transparency laws. “I always try to communicate on gmail because my NIH email is FOIA’d constantly,” he wrote in emails revealed by the subcommittee last year. “Don’t worry, just send to any of my addresses and I will delete anything I don’t want to see in the New York Times.”

The NIH claimed that it had investigated Morens, but Wenstrup demanded more inquiries on Tuesday, stating that the newly revealed emails suggest that “the NIH’s investigation missed important information” or even that there was “a potentially orchestrated coverup by the NIH FOIA office.”

The investigation into Morens’ FOIA practices spun off of a broader investigation into whether the coronavirus pandemic could have originated from a laboratory experiment.

In 2021, scientists enraged by reporting in The Intercept and other newspapers about the coronavirus discussed how they could counter the lab leak coverage. Morens, who was on the email thread, wrote that the NIH seemed interested in pushing back on the lab leak theory “but that Tony [Fauci] doesn’t want his fingerprints on origin stories.” And he discussed how to deal with journalists’ FOIA requests. Those emails caught the attention of House investigators.

Ironically, Morens’ tactics have made the story look much worse for the scientists. The emails suggest that he and his colleagues genuinely believe that the lab leak theory is misinformation and that the science points to a natural origin for coronavirus. But trying to hide documents makes it look like they have something to hide. It’s a classic case of the Streisand effect.

Let the story be a lesson to government officials everywhere. The one weird trick to evade FOIA doesn’t exist. Things that an official writes on the job are the people’s business, whether they’re recorded on paper or an email server. And although some tactics can slow down journalists, anything scandalous enough will leak and spread like an infectious disease.

Originally published by Reason Foundation. Republished with permission.

For more from Budget & Tax News.

For more public policy from The Heartland Institute.