Life, Liberty, Property #65: tariffs are flat-rate taxes paid for by consumers, which is preferable to the progressive income tax.

by S.T. Karnick

IN THIS ISSUE:

- Trump Talks Tariffs

- Shooting Down Judicial Activism

- Government Loans Are Unconstitutional

- Cartoon

SUBSCRIBE to Life, Liberty & Property (it’s free). Read previous issues.

Trump Talks Tariffs

Trump Talks Tariffs

On Thursday, former president Donald Trump made what may turn out to be one of the most controversial statements he has ever uttered. Speaking to Republican lawmakers in Washington, D.C., on Thursday, Trump floated the idea of cutting income tax rates and using tariffs to replace that revenue, in addition to renewing the 2017 tax cuts and exempting tips.

Bloomberg reports:

“He does want to look at lowering the income tax, and that could be offset and paid for by some type of tariffs, particularly on adversarial nations,” Representative Nicole Malliotakis, a New York Republican, said following the meeting.

Republican lawmakers, including some who have been skeptical of higher tariffs, said Trump’s pitch was well received.

“President Trump simply floated the idea as one of many brought up during the conversation, and he has said many times that as tariffs on foreign countries go up, taxes on American workers can come down,” campaign spokeswoman Karoline Leavitt said in a statement. “President Trump’s top priority remains making the Trump Tax Cuts permanent.”

For well over a century, the consensus among economists and policymakers has been that tariffs do massive economic harm by raising prices, increasing businesses’ production costs, prolonging the lives of inefficient businesses and outmoded industries, tempting the government to subsidize industries hit by the tariffs, inviting lobbying for carve-outs and other advantages, and spurring retaliation that results in “trade wars” that compound these effects.

The Wall Street Journal immediately poured cold water on the idea:

After imposing certain targeted tariffs as president, Trump has talked throughout this campaign about a 10% across-the-board tariff on imported goods as a way to punish other countries and protect domestic industries. On Thursday, he went further, floating to House Republicans the idea of replacing the entire income tax system with tariffs. That is an arithmetically challenged plan that would reverse more than 100 years of progressive taxation and is virtually assured to raise consumer prices.

Reversing progressive taxation is a goal that free-market proponents generally support, so it is interesting to see the WSJ present that as a criticism. The raising of consumer prices is a much more pertinent critique. However, a tariff that replaces income taxes might not be a net harm to consumers as a group, because lower income taxes give households more disposable income.

It is also worth noting that income taxes artificially push prices down in comparison with tariffs or no taxes at all, which is an economic distortion that must cause some level of malinvestment and misdirection of resources.

When it comes to taxes and their economic effects, there is no free lunch.

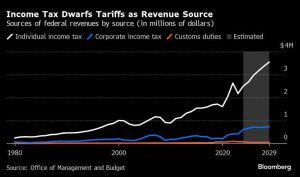

The WSJ is certainly right to observe that the current tariffs do not generate much tax revenue. A graph in the Bloomberg story illustrates this:

I don’t know about you, but I would prefer all of those lines to be as flat as possible.

Our free-market allies at the Committee to Unleash Prosperity say they’re “undecided on the wisdom” of Trump’s proposal, as am I. However, they rightly took it seriously in an item in their newsletter on Friday:

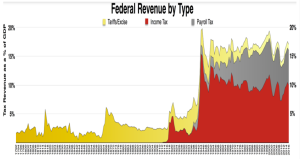

Tariffs were the number one source of revenues for the federal government. Then, the U.S. made one of its most grievous errors in history by adopting an income tax in 1913 via the 16th Amendment (which should be repealed).

The idea of replacing the evil progressive income tax with rates that exceed 40% and at one point reached 91%, and replacing it with a 10% flat income tax, would be pro-growth.

They further discuss the case as follows:

-

-

- Tariffs are taxes on consumption. It is better to tax consumption than to tax saving and investment.

- Tariffs are, of course, taxes, but a non-discriminatory revenue tariff on everything is far better than protectionist tariffs that try to prop up industry—cars, steel, solar panels, batteries, etc.

- We import nearly $4 trillion a year, so a 10% tariff could raise as much as $400 billion. That’s enough to completely replace what the corporate tax was raising before the Trump tax cuts.

-

I discussed the small-government, pro-liberty case for tariffs in issue #50 of this newsletter (see “Taxation with Misrepresentation”), writing about an article by economic historian Brian Domitrovic of the Laffer Center, from which I drew the conclusion that “the limitations of tariffs as a revenue-generating tool place a natural brake on government expansion and make them a natural choice for liberty-loving people who want a strong and fair economy.” (Domitrovic is a coauthor of the 2022 book Taxes Have Consequences: An Income Tax History of the United States, which has a foreword by Trump.)

I consider the revenue limitations of tariffs to be their greatest benefit. I contacted Prof. Domitrovic yesterday about Trump’s comment, and he affirmed that point: “What I find advisable about the tariff regime of old is that it put a cap on the size of government. Maybe 3 percent of GDP could be the maximum tariff revenue—then 3 percent was the size of government spending,” Domitrovic told me.

Domitrovic suggests that the revenue limitation of tariffs, as compared with income taxes, was crucial to the success of the 19th-century advance from an agricultural economy to the Machine Age: “I think this was the major reason that the tariff, even at high rates, was able to exist throughout the Industrial Revolution. It is fanciful to propose that had we had an income tax, there would have been an Industrial Revolution.”

Tariffs can spur innovation and entrepreneurship by decreasing the weight that income and corporate taxes impose on the economy. It is true that tariffs cannot fully replace the revenues those taxes bring in. That is good. We need to decrease the government’s diversion of the nation’s output of goods and services. Tariffs can limit the damage income and corporate taxes do. That is very good.

The partial replacement of income taxes with tariffs could put the United States on a much sounder economic footing, Domitrovic says.

“I don’t think a tariff could reel in nearly 20 percent of GDP,” Domitrovic told me. “But an increased tariff and a radically reduced income tax could work. A 10 percent income tax would badly devalue exemptions, etc. and collect around 10 percent of national income. That and a 5 percent tariff—OK, Trump wants more—and we would be in business. The growth would be epic, and I think the willingness to lend to the USA would soar.”

As to the effect on prices, income taxes are by no means neutral, Domitrovic notes. “OK, [tariffs could cause] a big increase in consumer prices—but what are the harms of a 40 percent income tax? Certainly that’s felt in prices. Labor compensation that has to take into account income taxes raises prices.”

Trump has said some dubious things over the years, but his suggestion to use tariffs to decrease the income tax is not one of them, in my view.

None of this is to suggest that Trump’s case for tariffs is a slam dunk by any means, or even that it is a good idea. What it certainly is, however, is worthy of an honest discussion.

Sources: Bloomberg; The Wall Street Journal; Committee to Unleash Prosperity; Heartland Daily News

Shooting Down Judicial Activism

Shooting Down Judicial Activism

The U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling on Friday striking down the Trump administration’s ban on bump stocks is another in a series of important decisions in the past few years, as a further indication of the Court’s evolution away from judicial activism to textualism under Chief Justice John Roberts. As The Daily Caller reports,

In a 6-3 ruling, the Supreme Court held that the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) exceeded its authority when it issued a rule classifying firearms equipped with bump stocks as machine guns. The case, Garland v. Cargill, challenged the ban enacted following the 2017 Las Vegas concert mass shooting, which the ATF implemented by interpreting a federal law restricting the transfer or possession of machine guns to include bump stocks.

“Semiautomatic firearms, which require shooters to reengage the trigger for every shot, are not machineguns,” Justice Clarence Thomas wrote in the majority opinion. “This case asks whether a bump stock—an accessory for a semiautomatic rifle that allows the shooter to rapidly reengage the trigger (and therefore achieve a high rate of fire)—converts the rifle into a ‘machinegun.’ We hold that it does not and therefore affirm.”

Reuters describes bump stocks as “devices that enable semiautomatic weapons to fire rapidly like machine guns,” in its story on the ruling. My disagreement with that description is that “semiautomatic” is a fudge word meaning “not automatic.” Still, the description of what bump stocks do is accurate.

The decision and dissenting opinion are particularly interesting in that the Court’s majority concentrated on the language of the regulation and the law on which it was based, and the minority seems to have based its objections mainly on the presumed consequences of the law: “Writing for the dissenters, Justice Sotomayor accused the conservative majority of once again turning a blind eye to the reality of gun violence, and making it yet more difficult to adopt measures aimed at preventing bloodshed,” NPR legal correspondent Nina Totenberg writes.

However, in what The Hill described as “a fiery dissent” that “harshly denounced” the Court’s majority decision, Sotomayor also attended to the language of the law and statute in question to support her case for upholding the ban. That too represents a major change from the Court’s 20th-century habit of using social science findings to justify many of its most influential and consequential decisions. Reuters reports:

In a dissent, liberal Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote, “Today, the court puts bump stocks back in civilian hands. To do so, it casts aside Congress’s definition of ‘machinegun’ and seizes upon one that is inconsistent with the ordinary meaning of the statutory text and unsupported by context or purpose.”

“When I see a bird that walks like a duck, swims like a duck and quacks like a duck, I call that bird a duck. A bump-stock-equipped semiautomatic rifle fires ‘automatically more than one shot, without manual reloading, by a single function of the trigger.’ Because I, like Congress, call that a machinegun, I respectfully dissent,” Sotomayor said.

The dispute might seem somewhat arcane, in that the words “by a single function of the trigger” in the National Firearms Act of 1934 and its later amendments are the crucial item of dispute.

It is, however, a good argument to have. A legal justification for government action—in this case a ban on a firearm accessory—should meet the strictest requirements for clarity and accuracy. The function of the Supreme Court in constitutional matters is to state when Congress and the president have gone outside their specified authority. Expansive interpretations of the law are unjust and unconstitutional, and the Court is obliged to strike them down.

Attorney Caroline Bermeo Newcombe made this point well in her 2022 article “Textualism: Definition, and 20 Reasons Why Textualism is Preferable to Other Methods of Statutory Interpretation,” in the Missouri Law Review:

Textualists also believe in legislative supremacy. Legislative supremacy is a doctrine which provides that when a court takes on the role of statutory interpreter, its role is subordinate to that of the legislature. The foundation of legislative supremacy is in Article I of the Constitution. The doctrine is designed to preclude “judicial policymaking” when a statute [is] clear.

An important characteristic of the doctrine of legislative supremacy (as well as textualism itself) is that textualist judges believe that they should still follow the text of a statute, even if they may not personally like the result of a decision they make. Textualist Justice Gorsuch emphasized this when he testified that “a judge who likes every outcome he reaches is probably a pretty bad judge, stretching for policy results he prefers rather than those the law compels.” Similarly, about the doctrine of legislative supremacy, a law professor explained that “the court must give way, even if its own view of public policy is quite different” [footnote numbers removed].

Justice Brett Kavanaugh made a similar point in the Court’s decision on Thursday in FDA v. Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine, which rejected a case brought by pro-life doctors against the Food and Drug Administration’s approval of the abortion drug mifepristone. The Court threw out the case because the plaintiffs could not show that they had suffered or would suffer an injury the courts could properly redress—which is known as the question of standing. “By limiting who can sue, the standing requirement implements ‘the Framers’ concept of the proper—and properly limited—role of the courts in a democratic society,’” Justice Kavanaugh writes.

Reporting on that case and the decision in Starbucks v. McKinney, also released on Thursday, The Wall Street Journal notes the Roberts Court’s move away from consequentialism to textualism: “What the rulings really show, again, is that the current Court majority is putting the law first, even if it means a policy defeat for their political beliefs. The critics were wrong—again.”

Although the media have characterized the bump stock decision as a split along political lines—which it certainly was in terms of who appointed the various justices—of far greater importance is its basis in the difference between textualism/proceduralism and consequentialism. The former is the foundation of a sound, blind, justice system, and the latter is the basis for legislating from the bench.

Sources: The Daily Caller; Reuters; NPR; Missouri Law Review; The Wall Street Journal

Government Loans Are Unconstitutional

Government Loans Are Unconstitutional

The U.S. government lends money to all sorts of people, notes George Leef in an article for the American Institute for Economic Research, including to “people who want to give agriculture a try, to people who want to open up a business, to people who want to buy a house, and to students who want to go to college,” among countless others. “The feds are eager to lend you money—just go to this website and see what you are eligible for,” Leef writes.

None of this is legal under the U.S. Constitution, Leef argues:

The US Constitution includes carefully written rules for the government’s spending of money. Article I provides that Congress may appropriate money to be spent for certain objectives, and then only if the expenditure is for the general welfare, as opposed to the benefit of small groups or individuals. But neither Article I nor any other part of the Constitution deals with the government’s power to lend money. Was that merely an oversight on the part of the drafters that summer of 1787? Did they perhaps intend that the government should have carte blanche to lend money as officials thought best? Of course not. The right conclusion from the omission of a grant of power to lend is that no such power was contemplated.

This lending is generally stupid and wasteful because the incentive structures in government do not fit this purpose, Leef observes:

The bad results of the government’s various lending programs underscore the wisdom of the Founders in not allowing it. Many business and agriculture loans went bust and the housing bubble of 2007-08 was a result of federal meddling in the mortgage market. All loans have some risk, but when the lender stands to take a loss if the borrower can’t repay, he carefully balances the risks and rewards, often declining to accept the risk. But when government officials approve or guarantee loans, lenders don’t have to worry about taking the loss. They can be very generous, pursuing what they regard as socially beneficial goals, and never worrying about the losses the taxpayers will have to bear.

Federal government lending was a major contributor to the ruination of the U.S. higher-education system, Leef argues:

That has been especially striking in the case of college loans. Before the federal government decided to make college “accessible,” the cost of tuition was rather low and yet only a small fraction of the populace thought the cost was worth it. Our high schools did a pretty good job of preparing people for careers and there were few jobs for which a college degree was a requirement. Academic standards were generally high, maintained by scholars who cared about imparting the knowledge of their disciplines.

That began to change once federal student aid began flowing. More students decided to give college a try and many of them were less academically prepared for college-level work. The schools liked the new revenues that came with those students, so they started to incrementally make adjustments to accommodate them—grade inflation and curricular degradation. Professors were allowed or even encouraged to keep students happy with high grades. Courses that were easier and more fun started showing up in the catalogues. We also saw the beginning of courses aimed at specific identity groups where the emphasis was not on mastering a body of knowledge, but on absorbing the professor’s point of view about some social ill.

Another unforeseen consequence of federal student lending was escalating tuition and fees. As college officials realized that the government was putting lots of money in the pockets of students that could only be used to buy their product, they did the natural thing—they charged more. Thus, the cost of college was going up while the educational benefit from it was going down.

Government loans are wasteful, unconstitutional, and economically and socially destructive, Leef concludes:

I say that the Founders were right in giving the federal government no power to lend money. It leads to wasted resources and huge burdens on the taxpayers. If we ever want to get our fiscal house in order, we’ll need to stop government lending.

Leef is right. We should end all federal government loan programs. If Congress and the president refuse to do so, the U.S. Supreme Court should strike them down as unconstitutional. If that sounds idealistic, so be it.

Source: American Institute for Economic Research

Cartoon

via Comically Incorrect

For more great content from Budget & Tax News.

For more from The Heartland Institute.