TikTok therapists promote family estrangement therapy to young people as a step toward happiness, in a social media fad.

by

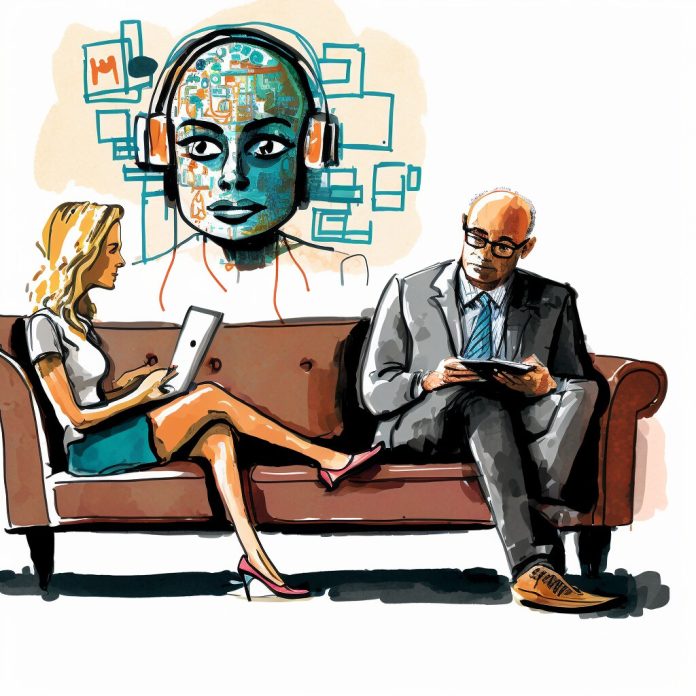

Public health advocates report there is a growing mental health crisis among young people, especially since covid. One outcome of mental health challenges is an emerging therapeutic estrangement fad on social media. I’m referring to the trend of TikTok therapists and sociology gurus on YouTube counseling young adults on becoming estranged from family members.

The New York Times told the story of a college student from Asia, whose parents incessantly badgered her to fulfill their expectations for her life. Their goals for her life and career were about their happiness, not hers:

That’s when she discovered Patrick Teahan, a licensed social worker from Massachusetts with tousled hair and a massive YouTube following. Mr. Teahan’s videos introduced her to a new idea — that to heal from childhood trauma, it may be necessary to “go no contact” from abusive parents. Around half of Mr. Teahan’s clients restrict or sever ties with their families, which he describes as “brutally hard” but, when it is appropriate, deeply rewarding. On Mr. Teahan’s website, you can fill out a “Toxic Family Test,” which measures your family on a 100-point toxicity scale… You can join his “Monthly Healing Community,” where clients support each other in the lonely endeavor of disconnecting from family.

Whether therapists should promote family estrangement is hotly debated in the mental health community. Among mainstream therapists, estrangement is considered extreme and usually reserved for the most toxic of relationships. The message that you can divorce your parents apparently gained a following with young people, and it has turned into a movement. One recent survey found that about one-quarter of Americans claim to be estranged from a family member.

Research suggests that it is relatively common for people in their 20s to estrange themselves from a parent, more often a father, and that usually the rift is not permanent. But promotion of estrangement as a therapeutic step is clearly on the rise, thanks mainly to social media. TikTok is coursing with first-person accounts from users who say cutoffs vastly improved their well-being. There is an expanding canon of self-help books on the subject, from “A Christian’s Guide to No Contact” to “Set Boundaries, Find Peace.”

Some young people are clearly better off setting boundaries (a phrase that us older people use). Others seem to dredge up false memories of childhood trauma and poor treatment that siblings and parents don’t recall. The New York Times contacted estranged family members to get their side of the story and sometimes recollections were very different. One mother likened estrangement to being “shunned,” although she admitted she had not been the best parent, due to alcoholism, borderline personality disorder and causing a volatile household while raising her kids. I’d probably want to shun her too.

By contrast a middle-aged Dallas therapist was blindsided when his 18-year-old daughter went no contact, claiming he always favored her brother and she struggled to get his attention. He described the estrangement as more painful than anything you could imagine.

As a result of more (mostly young) people cutting off their parents, support groups are springing up for people estranged from their family members. The parents too can join support groups of parents who’ve been estranged by their kids. One therapist who works with parents estranged by their kids explained it in plain terms:

“In my practice I see the generations talking past each other,” Dr. Coleman said. “Younger generations who are in therapy, they are coming to their parents saying they were traumatized, abused, neglected — and the parents are like, ‘What the hell are you talking about?’”

Behind this wave of estrangements, Dr. Coleman says, is an ever-lower threshold for what we view as “trauma.”

I recall back in the 1980s there was a psychology fad called Recovered Memory Movement. Under hypnosis or psychoanalysis counselors would supposedly help patients unearth long-forgotten memories of childhood trauma. Many people believed the memories were fabricated. An archived article in the New York Times recalls:

This was a time when therapists proudly advertised their ability to help clients unearth supposedly repressed memories of childhood sexual abuse; the accusations that followed shattered families and communities across the country. In 2005 a Harvard psychology professor, Richard McNally, called the recovered memory movement “the worst catastrophe to befall the mental health field since the lobotomy era.”

It’s hard to know what to make of the estrangement therapy movement. In 30 years, it may be remembered like the Recovered Memory Movement, or it may have evolved into a more nuanced therapy about setting health boundaries.

Originally published by the Goodman Institute for Public Policy Research. Republished with permission.