Life, Liberty, Property: Feds bail out depositors at SVB and Signature Bank, but won’t help banks that aren’t “too big to fail.”

You need to SUBSCRIBE to Life, Liberty & Property. (It’s free.) Read previous issues.

IN THIS ISSUE:

- Banks in the Tank

- Tapping Out in the Permian?

- Pension Tension

- Cartoon

Banks in the Tank

With two big bank insolvencies in the past week, fears of a systemic, cascading market crash are rising. Those are not implausible thoughts. For me, the greater fear is that the federal government’s and central bank’s attempts to shore up the system will be far more destructive than the demise of two banks.

Failures are instructive, not just destructive. Just as personal errors cause well-adjusted people to change course and direct their energies toward profitable activities, bank failures and other business blunders spur well-adjusted investors and managers to get on the right course.

Things only work that way, however, if those who make the mistakes are left to pay the price for them. History and literature are littered with accounts of wastrels whose parents or other well-meaning parties continually got them out of whatever trouble they brought upon themselves, until they dashed headlong into fatal disaster. Businesses, including banks, are made up of people, and they may follow the same course, if allowed.

The bailout culture created in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis has built just such an environment. That has led, over the 15 years since, to a massive misallocation of resources in the U.S. and world economies.

The U.S. Federal Reserve has notoriously contributed to that economic disturbance and normalization of moral hazard through a decade and a half of unusually low interest rates. The Fed recently decided to increase interest rates to tame inflation and encourage U.S. businesses to get out of risky and unproductive endeavors and into safer, more productive ones.

In the SVB and Signature debacles, the Fed got exactly what it wanted.

This has been a decade and a half in the making. Artificially low interest rates encourage investment in risker ventures than would otherwise be undertaken—because riskier investments must promise bigger returns. (Without that prospect, people would choose safer places to put their money, because it makes no sense to take a greater risk for the same potential return.) Multiplied manifold ways across the economy, the process results in increasing misallocation of resources away from profitable and welfare-maximizing activities into less-beneficial endeavors.

As Sheila Bair, chair of the U.S. Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) from 2006 to 2011, said in the recent Frontline documentary “Age of Easy Money,”

I can’t fault the companies so much because these interest rates, this interest rate environment, creates very strong economic incentives to do exactly what they’re doing. It’s hard to create a new product. It’s hard to come up with a new idea for a service. It’s hard to build a plant and hire people and run the organization. It’s real easy to issue some debt and pay it out to your shareholders to goose your share price. That’s really easy to do, but it doesn’t create real wealth; it doesn’t create real opportunity; it doesn’t create jobs. It doesn’t improve the labor market.

It’s just another example of how these very low interest rates have really distorted economic activity and, frankly, been a drag on our economic growth, not a benefit.

This mentality was evident in SVB’s business decisions, with easy money and the bailout culture as the promised backstop for any unwise moves. As The Epoch Times reported,

SVB was the banker of choice for many Silicon Valley tech startups and their venture capital funders that have benefited from the protracted period of loose credit. In just a few years, it grew into one of the 20 largest banks in the country, with some $200 billion in assets.

SVB had money to burn, and it incinerated plenty of it. The bank donated $73 million to Black Lives Matter and additional millions to other environmental and social governance and diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts, in an obvious bid by the bank’s directors to ingratiate themselves with their target market of woke Silicon Valley denizens, whose politics have rapidly transformed San Francisco and other blue cities from world-class tourist destinations into hellscapes where the city streets are now elongated public toilets.

More government regulation would not have averted the SVB and Signature debacles, nor will it prevent similar future calamities. Although SVB chose a risky area of investment, the bank was in fact doing what federal regulators advised, using long-term treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities to hedge against its core business of “volatile positions in technology and risky ventures,” in the words of fund manager, economist, and author Daniel Lacalle, as quoted by The Epoch Times. A steep drop in the value of those bonds, caused by the Fed’s interest rate hikes, pushed SVB into insolvency. As to “SVB’s unhedged $100 billion position in mortgage-backed securities,” the newspaper reports,

Lacalle noted that the Fed itself has designated those as low-risk, sitting on $2.6 trillion of them. If the Fed, as a regulator, was to declare mortgage-backed securities as risky, how could the Fed, as a monetary policy setter, declare them low-risk?

SVB and Signature are simply the most prominent victims thus far of the Fed’s effort to tighten the money supply to stop inflation. As The Epoch Times story notes, “When [SVB’s] investments started to underperform and its stock dropped, clients got cold feet and many moved their money elsewhere, triggering a bank run.”

There will be more news along these lines. The Fed is terrified of inflation and will trade a recession for it every time. Having suffered through the moral hazard easy money creates, we are now about to experience the economic destructiveness of tight money. Facing rising inflation and confounded by low unemployment rates (which the Fed takes to be a sure sign of excessively loose monetary policy instead of, say, a healthy demand for workers or a secular withdrawal of laborers from the economy for reasons having nothing to do with the money supply), the central bank raises interest rates to tighten credit, making investment more difficult. The riskiest ventures go under first. The Fed always stops tightening too late, however, and good enterprises soon get choked to death along with the bad ones.

As Bair notes above, easy money has driven down beneficial economic activity while rewarding speculation. This is not simple greed; it is common sense on the part of investors and indicates a fundamental distortion of the nation’s economy. Minneapolis Fed President Neel Kashkari expressed it well in the Frontline episode: “When companies are buying back their stock, one of the things they’re telling us is, ‘We don’t have profitable places to invest, and it’s easier for us to buy back our stock.’ … That’s not because of the Fed. … It really matters, but in my view it’s not something we control.”

Kashkari is right. The rise of stock buybacks and risky investment is clearly not a function merely of easy money but mainly of excessive difficulty in producing goods and services. Easy money is supposed to increase investment by making debt more attractive. If a large proportion of this easily obtained money is not going to productive enterprises, clearly something else must be wrong. Companies are putting their money in buybacks and risky investments instead of productive enterprises because truly beneficial economic activities are thin on the ground.

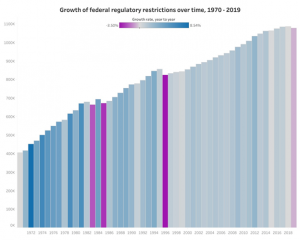

We need to explore why that is the case. If there is a shortage of “profitable places to invest,” it cannot be a matter of people not wanting more goods and services. People are always happy to have more if they can. It must be that it has become more difficult to provide these things. There is strong evidence for that conclusion. As the following charts indicate, federal government taxes and regulations are putting an increasingly heavy burden on the economy, and the labor participation rate is still below its pre-pandemic level (at least partly resulting from a big increase in government payments to individuals):

Yes, too much consumer money is chasing too few goods and services. That is why we have price inflation. There are, however, two ways to balance the supply of money and the supply of goods and services. One is to decrease the supply of money, as the Fed is now doing. That will create a recession, and probably in the present case a severe one. The other is to increase the supply of goods and services. The Fed does not have control over that.

The solution to our current problems is not to be found at the Fed.

Despite the dire scenarios that have been unfolding, our current economic plight can be solved easily and quickly. Cut government spending (starting with revocation of all the Biden-era spending increases), decrease tax rates, reduce regulation, and don’t let the government pay able-bodied people not to work. The only sticking point is the political headwinds against these simple and necessary reforms. However, the rapid economic rebuilding after World War II, the Kennedy tax-cut-initiated early 1960s economic expansion and restoration of American optimism, the Reagan boom, and the Trump economic recovery all show how quickly the American people can respond to positive fiscal and regulatory reforms.

We need to learn the right lessons from our failures. If we expect to solve our economic problems through tight money, worse times are on the way.

The U.S. economy is suffering from a massive misallocation of resources. The Fed contributed to that, certainly, but the real source of the trouble is the federal government. National fiscal and regulatory policies are punishing productive behavior and rewarding unproductive activities and idleness. Until that changes, economic ills will be the norm, and all efforts to remedy them through intervention by the government and the central bank will create further and more-damaging problems.

Source: The Epoch Times

Tapping Out in the Permian?

The U.S. shale boom is ending, The Wall Street Journal reports:

The boom in oil production that over the last decade made the U.S. the world’s largest producer is waning, suggesting the era of shale growth is nearing its peak.

Frackers are hitting fewer big gushers in the Permian Basin, America’s busiest oil patch, the latest sign they have drained their catalog of good wells. Shale companies’ biggest and best wells are producing less oil, according to data reviewed by The Wall Street Journal.

The return to a pre-pandemic drilling pace is beginning to exhaust the best wells, the WSJ reports:

Oil production from the best 10% of wells drilled in the Delaware portion of the Permian was 15% lower last year, on average, than top 2017 wells, according to data from analytics firm FLOW Partners LLC. Meanwhile, the average well put out 6% less oil than the prior year, according to an analysis of data from analytics firm Novi Labs.

Executives of major oil companies such as ConocoPhillips and Chevron are reporting declines in production, the paper reports.

Chief executive Rick Muncrief of Devon Energy Corp., however, sees no reason to panic, the WSJ reports:

“I’m not terribly surprised, and I’m not terribly alarmed,” he said, saying that wells drilled in the Boundary Raider area still generated excellent returns for the company. Mr. Muncrief said that tight crude supplies pushing oil prices higher would make tapping into less productive formations economically viable for operators.

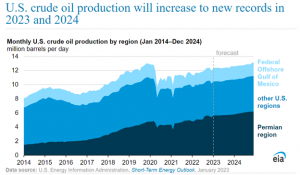

The U.S. Energy Information Administration agrees with Muncrief, forecasting record production of crude oil in the United States in 2023 and 2024:

In our January 2023 Short-Term Energy Outlook, we forecast that crude oil production in the United States will average 12.4 million barrels per day (b/d) in 2023 and 12.8 million b/d in 2024, surpassing the previous record of 12.3 million b/d set in 2019. In 2022, U.S. crude oil production averaged an estimated 11.9 million b/d. Increased production in the Permian region and, to a lesser extent, in the Federal Offshore Gulf of Mexico (GOM) drives our forecast growth in production. We base our forecast on our expectations of crude oil prices and infrastructure capacity additions.

Our forecast of crude oil production in the Permian increases by 470,000 b/d to average 5.7 million b/d in 2023. Completion of new natural gas pipelines will allow producers to transport more of the natural gas that is produced along with crude oil (associated natural gas) to market, removing a potential constraint on crude oil production.

It is in the interests of some companies, of course, to warn of coming shortages, given that expectations of future scarcity raise current prices. Just saying.

My Heartland Institute colleague Linnea Lueken, a research fellow in energy and environmental issues who formerly worked as a geologist on deepwater drillships in the Gulf of Mexico, told me predictions of production declines are a common occurrence:

While oil and gas are technically finite resources, their demise has been repeatedly thwarted by improvements in technology over the past several decades [Lueken said]. For the Permian, naysayers have come out of the woodwork every few years to claim that, very soon, the powerhouse of U.S. production will peak. So far, this hasn’t happened, and the best estimates of the quantity of oil there suggest that it won’t happen any time soon, at least not from a supply standpoint.

Pressure on oil companies against drilling new wells, intolerable regulatory environments, and an overall hostile presidential administration may make it more difficult from a logistics standpoint to continue developing the Permian. There seems to be little reason to think that all the best-producing wells have already been drilled there. After all, it was only four years ago that the [U.S. Geological Survey] announced they found that the Wolfcamp shale and Bone Spring formations are the largest continuous oil assessments yet. Oil and gas production in the Permian is currently smashing prior records.

Shale oil formations have special characteristics that can contribute to fears of imminent exhaustion, Lueken says:

Oil production from tight shale typically has a steeper decline curve than traditional wells. That does not mean that we are running out of oil in the entire Permian basin. It means that more wells need to be drilled regularly in the various oilfields of the Permian to keep production increasing or level, even as legacy wells fall off. Production can also be hindered by the availability of pipelines and refinery capacity.

For now, it appears that forecasts of upcoming shortages of Permian oil may be premature.

Source: The Wall Street Journal

Pension Tension

French President Emmanuel Macron has implemented a major change to France’s pension law, raising the retirement age from 62 to 64. Fearing the administration lacked the needed votes in the National Assembly, Prime Minister Élisabeth Borne invoked Article 49:3 of the French constitution to allow the government to proceed with the plan. Opposition members of the assembly jeered, shouted, and sang the national anthem in protest.

French President Emmanuel Macron has implemented a major change to France’s pension law, raising the retirement age from 62 to 64. Fearing the administration lacked the needed votes in the National Assembly, Prime Minister Élisabeth Borne invoked Article 49:3 of the French constitution to allow the government to proceed with the plan. Opposition members of the assembly jeered, shouted, and sang the national anthem in protest.

Tens of thousands of people have protested across the country, and police used tear gas to break up demonstrations in Paris.

Pensions in France are unusually generous, eating up 14.5 percent of the nation’s economic output, compared with 7.5 percent in the United States and 10.4 percent in Germany, according to the OECD as reported by The Wall Street Journal. An independent French advisory panel says the system will run a €1.8 billion deficit this year, €10.7 billion in 2025, and €21.2 billion in 2035. The deficits are being driven by demographics, the WSJ reports:

The golden age of French pensions is coming to an end, one way or another, in an extreme example of the demographic stress afflicting the retirement systems of advanced economies throughout the world.

As people live longer and the population grows older, the number of active workers who fund each pension check is shrinking. France had more than four workers for every retiree in the early 1960s, according to the government. That figure stood at 1.7 in 2020, and it is projected to fall to 1.5 over the next decade, according to an independent panel of economists, lawmakers and union leaders advising the government on pensions.

Given those numbers, Macron argues the current system is unsustainable. That is surely true.

We can expect similar controversies to arise in other developed countries in the years to come as demographics once again prove to be destiny. The recent spat over President Joe Biden’s State of the Union claim that unnamed Republicans were planning to cut Social Security will in retrospect look like a time of unusual peace and harmony.

Source: BBC News

Subscribe and Get Smarter

Cartoon