Life, Liberty, Property #62: Dow passes 40,000 mark, but people are struggling with mortgage and rental costs.

IN THIS ISSUE:

- Dow 40,000

- The Path to a Humane Economy

- SNAP Abuse

- Cartoon

SUBSCRIBE to Life, Liberty & Property (it’s free). Read previous issues.

Dow 40,000

The Dow Jones Industrial Average surpassed a major milestone last week, rising above 40,000 on Thursday before sliding back down to 39,869, and going up again above 40,000 for Friday’s close.

That represents a 40 percent increase over the stock market’s September 2022 recent low.

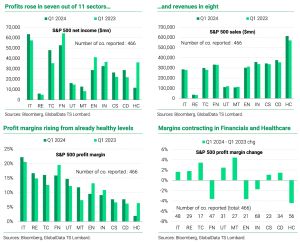

Part of the explanation is that profits are up:

Source: Andrea Cicione – TS Lombard

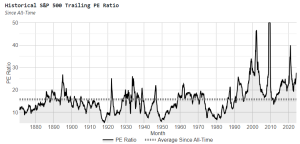

One might well argue, however, that price/earnings ratios are too high at present, as the following charts suggest:

Source: Stock Market PE Ratio

But OK, we’ll leave that aside and grant that the recent rise in profits makes stocks more attractive. Why are profits up? Let’s examine some things about the overall economy.

Side note: I am on the record as saying, “This economy does not look good,” as recently as three weeks ago (Life, Liberty, Property #59). That might seem a bit dumb now, but I’m not so sure.

The Dow appears to be anticipating an easing up on money tightening by the Federal Reserve (Fed). The Wall Street Journal reports,

Data Wednesday showed that core consumer prices, which exclude the volatile categories of food and energy, last month posted their smallest increase since April 2021. The Dow climbed after the inflation report and then crossed 40000 Thursday before paring its gains.

Clearly, investors are thinking that the slight slowing of inflation in April means the Fed will soon relent on its tightening of the money supply via higher interest rates and reductions of its holdings of federal government bonds. Conventional (i.e., Keynesian) thinking is that the reduction of interest rates will allow the economy to expand more rapidly (by making it less-expensive to borrow for consumer spending and business investment).

The increase in interest rates in the past two years has not hurt the economy, it would seem: “Yet interest rates remain much higher than in the years before the pandemic,” the WSJ reports. “The yield on the benchmark 10-year Treasury topped 5% in October for the first time in 16 years. It has since fallen to 4.376%, still more than double its 1.909% level at the end of 2019.”

Thus, “the recession predicted by so many economists hasn’t materialized, giving investors hope that stocks might keep climbing,” the WSJ reports. “‘Not only didn’t we have a recession, we had a robust economy with tight labor markets, healthy consumers who were consuming,’ said Katie Nixon, chief investment officer for Northern Trust Wealth Management.”

As the quote from Nixon indicates, U.S. economic growth has been driven by expansive consumer spending since 2021, surprising those who thought that the interest rate increases would bring on a recession. This demand-driven expansion might cause some to agree with a phrase often misattributed to another Nixon (the economy-destroying President Richard Nixon): “We are all Keynesians now.”

I have a different theory: Could it be that the ongoing increase in housing prices is helping to spur this consumer spending? Not exclusively, of course, but as a big contributing factor? (This increase in housing prices, by the way, is mainly a result of overall price inflation plus governments’ suppression of housing construction plus immigration increasing the demand for housing.)

House prices and mortgage payments have risen rapidly in recent years, especially since 2020:

Source: Regime Critic

People are reluctant to sell their houses given the costs of buying another, and that reluctance cuts the supply of houses available to buyers, which contributes to further price hikes for the houses that do go on the market. Meanwhile, interest rates have risen, as noted above. That adds more to the cost of a new house.

As a result, the median monthly mortgage payment for a new house is almost double what it was in 2019.

Median household income rose by 17.8 percent between 2019 and January 2024 (from $65,712 to $77,397). The median sales price for a new home in the United States rose by more than double that: 39 percent (from $310,600 to $430,700). (Note: in April, the median price hit a new record high, at $433,558, raising the increase to 40 percent. That is a 6.2 percent rise year-over-year.)

The median monthly payment for a home purchase was $2,775 in the four weeks ended April 14, The Wall Street Journal reports. In 2019 it was $1,242. That means the percentage of the median household income required to pay the mortgage on the median-priced house rose from 22.7 percent in 2019 to 43 percent today. That is a truly awful number.

Home equity accounted for 65 percent of Americans’ household wealth in 2021. According to Federal Reserve numbers, U.S. homeowners in 2019 had a median net worth of $293,900, whereas renters’ median net worth was just $7,230. That means homeowners had more than 40 times the wealth of renters.

On paper, that is. You have to live somewhere, so if you sell your increasingly valuable house, you have to buy … some other increasingly valuable house.

As a result, the housing supply is “historically low,” according to Redfin. “Homeowners who would like to move are staying put so they can hold on to their lower-rate mortgages,” the WSJ reports in its story on the Dow record. “The resulting lack of homes for sale has pushed prices beyond the reach of many prospective buyers.”

If you do not move, however, the rise in the value of your house increases the amount of money you can borrow against your rising home equity.

It makes sense that a simultaneous increase in house valuations and inability to sell one’s home would funnel money toward other purchases and investments. If people are not buying new homes, they have more ready cash to spend on other things—a lot more than in previous years, in fact, given the rise of homeowners’ equity as the calculated values of houses rise.

Thus, the U.S. economy has been expanding via a rapid increase in household borrowing, which has fueled increases in consumer spending, pushing up prices of services in particular. These are price hikes, not wealth increases.

A rising Dow and expanded household borrowing make great sense in this context of rising housing values. These are increases in spending, however, not necessarily indicative of rises in the real value of goods and services. As Josiah Lippincott notes at his Regime Critic Substack:

The cost of food, housing, and transportation have nearly doubled in the last five years. In effect, the value of the starting salary for new college graduates has fallen by almost half. The median new college graduate salary today is the equivalent of making $12 an hour in 2019.

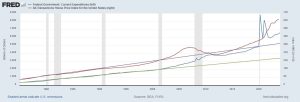

As I have noted regularly in this newsletter and elsewhere, federal government overspending fuels inflation. Here’s a little graph I made that shows how the rise in federal spending compares with the rise in housing prices:

Note the two trendlines: green for the 1970-2000 trend in federal spending, and purple for the trend in the housing price index for those years. Federal spending moves above trend in 2000 and much above trend in 2021. Housing prices move above trend in 2000, and much above trend in 2021.

That is no coincidence. The increase in housing prices is being caused by more than a rise in the quality of housing—the latter does contribute over time, but not over the course of two or three years. The price increases track well with federal spending because the latter is increasingly funded by deficits, which create inflation via Fed monetization of the increasing federal debt.

Meanwhile, real (inflation-adjusted) stockholder wealth has risen to 10 times its value of four decades ago, the Committee to Unleash Prosperity (CTUP) reports.

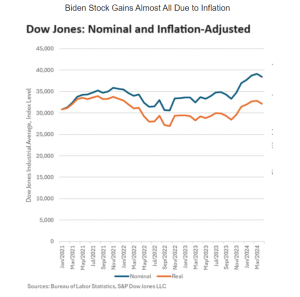

That is real monetary wealth, in the sense of being inflation-adjusted, but does it represent greater real value of goods and services across the economy? Not since 2021, it doesn’t. Whereas “the vast majority of the gains from the past four-decade-long bull market from—Reagan through the Trump presidency—were REAL gains, not inflationary gains,” CTUP notes in another article, “about 80% of the stock rise during Biden’s tenure has been phantom gains due to inflation.” CTUP’s chart illustrates this increasing gap:

Source: Committee to Unleash Prosperity

Given these factors, the recent rise of the Dow does not appear to be indicative of a great increase in the real value of goods and services produced in the United States.

In addition, “these illusionary gains are subject to taxes since capital gains aren’t indexed to inflation.” Naturally, then, as part of President Joe Biden’s campaign to intensify the excessive deficit spending and overregulation that have created this Potemkin economy, the administration wants to increase capital gains taxes radically. Biden proposes a near-doubling of the percentage taken from high-income taxpayers with long-term gains—to 39.6 percent from the current 20 percent—and more than double for some taxpayers, who will pay 44.6 percent.

(Of course, they won’t really pay this, as I noted in Life, Liberty, Property #58. It is all a circus show designed to get suckers to vote for Democrats and Rinos. The latter label applies to nearly all Republicans, alas.)

In summary, the federal government’s economic destruction is real, ongoing, and intensifying.

So, congratulations to those of my readers who have lots of money invested in Dow stocks. I am truly happy for you.

Overall, however, I’ll say it again:

This economy does not look good.

Sources: The Wall Street Journal; Regime Critic; The Wall Street Journal; Redfin; Committee to Unleash Prosperity

The Path to a Humane Economy

In the article at Regime Critic I cited above, Josiah Lippincott argues that “our economy is unhealthy,” which it certainly is. “Americans work way too much,” Lippincott observes. “Simply staying afloat in this economy as a middle-class household usually requires that both husband and wife work full-time. Americans notoriously have relatively few vacation days when compared to workers in other advanced economies.”

Lippincott argues from a quality-of-life perspective as opposed to a straightforwardly materialistic, Economic Man point of view focused on the continual rise of numbers suggesting (but by no means proving) a consistent increase in material wealth. The quality of life being fostered by human action should be an important element of any discussion of economic affairs and of government policy, in my view.

Lippincott argues, correctly, that government policies are making work less attractive and are actively encouraging people to drop out of the labor force—while importing people from other countries and alien cultures to replace the native-born Americans whom these policies have driven out of paid employment, which just happens to reduce labor costs for big businesses that contribute massive amounts of campaign money to politicians:

Yet even while Americans are throwing themselves ever more intensely into the grind of corporate life for ever less money, homelessness and welfare usage are ballooning. Tens of millions of adult Americans don’t work at all or only part time, surviving off of government benefits like disability instead of holding down employment. …

Americans who should be working are not. Other workers are throwing themselves into the corporate grind, sacrificing their youth in exchange for declining wages, higher taxes, and a lower quality of life. …

In America, an 18-year-old with a high school diploma and average intelligence should be able to find a job that allows him to pay off the mortgage on a 1600 square foot home in 15 years without needing to pay more than a third of his income per month towards housing. That might sound like a ridiculously high bar in the brutal conditions of Joe Biden’s inflation-ridden economy, but this kind of life isn’t impossible. In fact, within living memory, such economic conditions existed.

Lippincott calls on businesses to reform their treatment of workers, which is a fine ideal but not likely to occur under the current regime of heavy government regulation and explicit manipulation of the economy for the benefit of big political-campaign donors. Lippincott advocates a generally Trumpian/National Conservative policy approach combined with some explicit pro-market reforms (such as relaxation of the multitude of laws against property improvements and an end of government subsidization of colleges and universities):

By deporting immigrant scab labor, slowly raising tariffs on manufactured goods, and easing absurd zoning and environmental requirements we can build an economy that is much better for blue-collar Americans. That is a political platform worth fighting for.

We should work to assist white-collar workers as well by disrupting the college industrial complex. The federal and state government should cut off aid to higher education in exchange for forgiving the bulk of Americans’ student loan debt. This would cause most American colleges to go belly up, a nearly unrequited good for the country as a whole. Shutting down leftist indoctrination centers that hold the keys to higher salaries and political and cultural power is a good idea.

The goal of Lippincott’s policy suggestions is a more-humane economy:

At the blue-collar level, American trade and foreign policy should be aimed at cultivating industries in America that can [employ] a person of ordinary intelligence straight out of high school in trades and professions that can provide a good middle-class life. The nature of blue-collar work is such that a more rigid schedule with longer hours need[s] to be the norm.

The tradeoff should be that these workers get to make a good salary with nice benefits without the need for having a high-IQ, lots of credentials, or connections. The American labor market should be such that we always have a “shortage” of labor. In other words, wages should be high and benefits good. In that economic market, there is hardly even a need for unions. Ordinary market forces will propel salaries upwards.

The enhancement of job prospects and income for people who are willing to do real work is a laudable goal. Of course, insofar as big corporations wield power through campaign donations, possible future jobs for ex-lawmakers, etc., government policy will attempt to produce labor gluts, not shortages, so that wages will be as low as possible. Note how often the Federal Reserve worries about unemployment being too low.

The reduction of wages is half the reason for mass immigration being allowed (both legal and illegal), as it is seen to benefit business (by lowering expenses) and socialists (with immigrants’ votes), a classic bootleggers-and-Baptists situation.

This aspect of public choice theory is also why the National Conservative elements of Lippincott’s policy mix will not accomplish what he wants them to: they will be corrupted from the moment that politicians even begin to consider them.

The only viable path to the humane economy Lippincott quite properly advocates is a prodigious reduction in federal government power, which would dramatically reduce all these influences over economic policy—because they could not be implemented.

We should try downsizing government first, and then see what, if any, government interference is required for a truly humane economy. I say that there is just about none, other than maintenance of a fair and just tort system, though I am willing to go wherever the evidence leads.

I invite the National Conservatives and others who want a humane economy to do the same.

Source: Regime Critic

SNAP Abuse

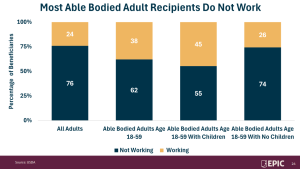

The Biden administration and multiple states are misusing the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) to give taxpayer money to people who can work but do not, Matthew D. Dickerson, director of budget policy at the Economic Policy Innovation Center, shows in his newly released Food Stamp Chartbook:

Interestingly, among able-bodied adults aged 18-to-59 years, those with children are more likely to work than childless ones, as the chart above shows. That indicates the program is subsidizing indolence among the latter, as they do not even have the excuse of being occupied with the raising of children. Recipients with children show a greater likelihood of trying to improve their lot in life.

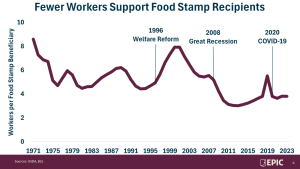

The subsidization of joblessness is shrinking the workforce and placing a greater burden on those who do work (now through taxes, and both now and later through federal debt):

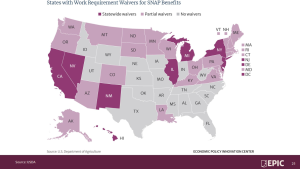

The Biden administration and blue states are abusing a loophole in the law, the Committee to Unleash Prosperity notes:

New modest federal work requirements have begun to kick in, but most blue state pols aren’t enforcing that law or have waived the mandate. Democrats view food stamps as an economic stimulus and/or virtuous income redistribution.

The villain here is the Biden administration (and Congress) that refuses to mandate work for welfare. This was a hallmark of the Clinton administration reforms in 1996. Now work requirements are regarded as cruel.

There is a clear red-state/blue-state difference in the granting of waivers, indicating that this is a political issue and not simply a matter of greater need or humanitarian impulses, as a chart by Dickerson illustrates:

SNAP is another corrupted federal government welfare program that needs serious reform.

Sources: The Food Stamp Chartbook; Committee to Unleash Prosperity

Cartoon

Via Townhall.com

For more great content from Budget & Tax News.

For more from The Heartland Institute.