Minnesota Supreme Court asked to uphold rights of native American kids against discrimination in child welfare in Goldwater Institute brief. (Commentary)

When 2-year-old twins Kara and Karl (not their real names) were born, they faced some terrible challenges. Their mother was unable to care for them, and, worse, she had used drugs during pregnancy, so the babies suffered symptoms of withdrawal and other health complications; Kara wasn’t even breathing when born.

Fortunately, they weren’t far from Minnesota’s world-famous Mayo Clinic, where they were taken for intensive care to help with their seizures and other symptoms. And they were placed in the home of a loving foster couple who were able to provide them with the care and attention they needed.

But Kara and Karl also have Native American ancestry. That means they fall under the federal Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) and the state version, called the Minnesota Indian Family Preservation Act (MIFPA). Together, these laws impose a separate set of rules on cases that involve “Indian children”—rules that are less protective of the children’s welfare than the rules that apply to kids of other races.

The result is that Kara and Karl will probably not get the first-rate medical attention and other care they need. That’s unconstitutional—and that’s why the Goldwater Institute is working with American Freedom Network member Mark Fiddler to represent the twins’ foster parents in a lawsuit before the Minnesota Supreme Court.

The case began when the twins were a year and four months old, and officials from the Red Lake Nation demanded that the kids be taken from the foster parents (known in court briefs as K.R. and N.R.) and sent to live with a cousin of their mother, whom the kids had never even met. The twins’ birth mother objected, arguing that her cousin wasn’t capable of taking care of the kids—and K.R. and N.R. joined in that objection, seeking to intervene in the lawsuit to defend the kids’ best interests.

Sadly, while courts normally prioritize the “best interests of the child” in cases involving children, the rules are different for “Indian children”—a term the law defines as kids who are either members of a tribe or are eligible, based solely on their biological ancestry, for tribal membership. For white, black, Asian, Hispanic, etc., kids, a child’s best interest as an individual is what matters: what this child needs, in his or her specific situation. But in cases involving “Indian children,” the child’s best interests are determined under a different rule: courts must consider the tribe’s interest, as a government entity, as if it’s equivalent to the child’s interest.

What’s more, both ICWA and MIFPA establish different evidentiary standards for cases involving “Indian children”—standards that are less solicitous of the child’s welfare than the rules applying to other kids. These laws require state judges to transfer cases involving “Indian children” to tribal courts where the Bill of Rights doesn’t apply. And they require state child protection workers to send abused “Indian children” back to households known to be abusive.

When K.R. and N.R. filed their lawsuit, a trial judge threw the case out on the grounds that they weren’t even allowed to intervene. The Minnesota Court of Appeals reversed that decision, holding that they could participate in the case—but it went on to reject their arguments that ICWA and MIFPA are unconstitutional race-based statutes. It cited a 1974 U.S. Supreme Court ruling that said the government can treat Indians differently from non-Indians without violating the rules against racially discriminatory laws.

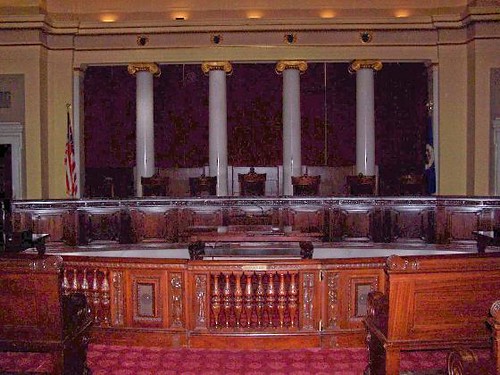

Now the case is before the Minnesota Supreme Court, where we’ve filed a brief arguing that that 1974 ruling doesn’t apply here, and that both the state and federal laws discriminating against “Indian children” do, indeed, violate the rules against racially discriminatory statutes. You can read our opening brief here.

(Last year, in Haaland v. Brackeen, the U.S. Supreme Court refused to decide whether ICWA is unconstitutionally race-based, because it said that nobody involved in the case had standing to raise that question.)

ICWA and its state versions such as MIFPA were written with good intentions—to protect Native American families against abusive state governments that had previously tried to break up Indian families. But in today’s work, these laws actually serve as one of the leading obstacles to the protection of Indian kids against neglect, abuse, and other harms.

In fact, in case after case, these laws have led to the preventable murders of Native American kids. Native kids are the most at-risk demographic in the United States, facing a greater risk of everything from molestation to gang activity to suicide than any other group of American children. There are families out there willing to help—people like K.R. and N.R. who are willing to open their hearts and homes to these children. Yet ICWA and MIFPA stand in the way, based solely on a child’s skin color.

Karl and Kara have enough challenges. Their race shouldn’t be one of them. The Goldwater Institute is proud to stand up for them. You can read more about our work challenging the constitutionality of ICWA here.

Goldwater Institute brief here.

Timothy Sandefur is the Vice President for Legal Affairs at the Goldwater Institute.

Originally published by the Goldwater Institute. Republished with permission.

For more Rights, Justice, and Culture News.