By Edward Ring

A historic barrage of atmospheric rivers hit California. Across the Sierra Nevada and down through the foothills into the valley, rivers turned into raging torrents, overflowing their banks and flooding entire communities. California’s Central Valley turned into an inland sea, as low lying farms and grasslands were incapable of draining the deluge.

That was 1861, when one storm after another pounded the state for 43 days without respite. Despite impressive new terminology our experts have come up with to describe big storms in this century – “bomb cyclone,” “arkstorm,” and “atmospheric river” – we haven’t yet seen anything close to what nature brought our predecessors back in those pre-industrial times over 150 years ago. But we are getting rain this year. Lots of rain.

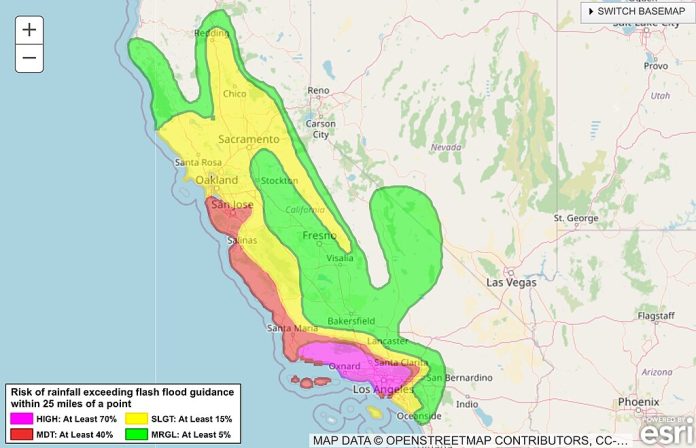

According to the National Weather Service, by the time 2024’s first two atmospheric rivers are done with California, the state will have been inundated with an estimated 11 trillion gallons of water. That’s 33 million acre feet, in just 10 days. Are we harvesting this deluge? In this new age of climate change, which purportedly portends years of drought whipsawing occasionally into a year or two of torrential rain, do we have the means to take those so-called big gulps into storage?

Rather than speculate over California’s glacial (poor choice of words) progress towards ways to harvest more water from storms in a state too warmed up to ever have a big snowpack again (except for last year, and maybe this year), how are we using the assets we’ve already got?

To answer that question, one must navigate the arcane recesses of the California Dept. of Water Resources website, and reference their “historical data selector.” Using this interface it is possible to determine for any day or range of days, how much water flowed through the Sacramento San-Joaquin Delta into the San Francisco Bay, and how much water was diverted into southbound aqueducts by the pump stations located near the City of Tracy on the southern edge of the Delta.

This data may be arcane, but it isn’t ambiguous. During the first 36 days of 2024, through February 5, 2.05 million acre feet have passed through the Delta and out into the SF Bay, and 356,000 acre feet has been pumped into aqueducts. That is, of the 2.4 million acre feet that flowed through the Delta so far this year, 15 percent of it has been saved. That’s not much. But the devil is in the details.

Around this time of year, to protect fish, the “Integrated Early Winter Pulse Protection Action” is put into effect. For two weeks, pumping is restricted to prevent the possibility of endangered fish – allegedly pushed downstream by storm driven accelerated current in the Delta – from getting trapped in the powerful pumps that lift water out of the Delta and into the aqueducts. But where is the evidence that turning down the pumps is doing any good? If this is about the endangered Smelt, and if they are so critical to the Delta ecosystem, where are they?

If the environmental benefits of restricted pumping during storms are debatable, the consequences are not. During the first 22 days of 2024, before the pumps were turned down, 24 percent of the outbound Delta flow was diverted into the aqueducts. On average, 36,000 acre feet per day flowed out of the Delta and into the ocean.

During the subsequent 14 day partial shutdown of the pumps, 89,000 acre feet per day was permitted to flow out to the ocean. Between January 23 and February 6, the Delta pumps were operating at a mere 27 percent of capacity during not one, but two major storms. During this period, if both Delta pumps had operated at full capacity, the daily flow from the Delta into the San Francisco Bay would still have been 187 percent more than the pre-pulse flow, and an additional 297,000 acre feet could have been diverted to flow south and into storage.

Turning down the pumps for these past two weeks, therefore, deprived Californians of a quantity of water that is arguably worth billions. Let’s not forget that our state legislature intends to spend $7 billion (before overruns) to restrict urban water use to 42 gallons per day per person and kill all “nonfunctional” lawns, in order to save around 400,000 acre feet per year.

The activists, ideologues, vendors, contractors, consultants, nonprofit corporations, journalists, opinion shapers, and experts that control and serve California’s state water agencies need to consider their credibility outside their own powerful echo chamber. Restricting Delta pumping during two big storms is another example of how they are squeezing the life out of farmers and urban water agencies, and by extension, the people of California. But watch out. Spring is coming, and it isn’t just rain clouds that are clearing up.

For the last 40 years, agency scientists have been able to set policy without serious opposition. This unwarranted bureaucratic power is based on the landmark case Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc.” It finds that “when a legislative delegation to an administrative agency on a particular issue or question is not explicit but rather implicit, a court may not substitute its own interpretation of the statute for a reasonable interpretation made by the administrative agency.”

What that ruling has done is empower activist bureaucrats hired by biased government agencies to present analysis developed internally or through contractors, and turn that analysis into policy, and if anyone challenging these expert opinions brings their own equally credentialed experts into the courtroom, the judge is required to defer to the government agency’s experts and disregard the plaintiff’s experts. But the precedent set by this 1984 case was challenged before the US Supreme Court last month, with a ruling expected later this year.

If courts are no longer required to defer to an agency’s expert, California’s water agencies are going to have a lot of explaining to do, starting with why they’re letting millions of acre feet of fresh water pour into the San Francisco Bay every year, during “bomb cyclones” that, even while they wreak fury on the state, also bestow plenty of water for fish and for people.

Edward Ring is a contributing editor and senior fellow with the California Policy Center, which he co-founded in 2013 and served as its first president. The California Policy Center is an educational non-profit focused on public policies that aim to improve California’s democracy and economy. He is also a senior fellow of the Center for American Greatness. Ring is the author of two books: “Fixing California – Abundance, Pragmatism, Optimism” (2021), and “The Abundance Choice – Our Fight for More Water in California” (2022).

Originally published by the California Globe. Republished with permission.

To read more about water issues in California, click here and here.