Life, Liberty, Property #42: I offer myself as a highly reliable Budget Commission, able to cut spending instead of raising tax rates, says Senior Fellow S.T. Karnick.

By S.T. Karnick

IN THIS ISSUE:

- I Offer Myself As a Highly Reliable Budget Commission

- What Is Income?

- The Fed’s Unemployment Fetish

SUBSCRIBE to Life, Liberty & Property (it’s free). Read previous issues.

I Offer Myself as a Highly Reliable Budget Commission

The House Budget Committee is thinking about calling for a fiscal commission to come up with ideas for reducing the federal government’s persistent and rapidly growing budget deficits. The Center Square reports:

The House Budget Committee discussed the pros and cons of a bipartisan, bicameral fiscal commission. While Democrats and Republicans have different ideas about how to address the longstanding issue, members of both parties indicated support for such a commission.

“Different ideas” means Democrats are eager to raise tax rates and impose unconstitutional wealth taxes, and Republicans want to cry. The budget deficit has reached a crisis level, the Center Square story notes:

The cost of borrowing money is taking up a larger share of the federal budget, which along with the rising costs of Social Security and Medicare, are driving up the national deficit.

Interest costs on the country’s $33 trillion debt increased 23% to $879 billion in fiscal 2023. That’s a record high. Interest costs accounted for 14% of total federal spending as of September 2023. The cost of maintaining that debt is expected to grow. The Congressional Budget Office released projections in June that showed interest costs would “exceed all mandatory spending other than that for the major health care programs and Social Security by 2027, all discretionary outlays by 2047, and all spending on Social Security by 2051.”

The Budget Committee would like to have somebody else to blame for what must happen. There are only two ways to decrease the budget gap: cut spending, and/or increase revenues. Democrats will not consider cutting spending. If a commission tells Congress to cut spending, the report will be thrown directly into the trash. That means they will look for ways to increase revenues.

Republicans do not want to raise tax rates, but they will agree to do so if the Democrats consent to some spending cuts. Oh, not spending cuts, really, but a future decrease in projected expenditures. What we will get, as we always do, is tax rate hikes in exchange for more spending larded onto the budget a few months later.

Here’s what federal spending looks like:

Source: St. Louis Fed

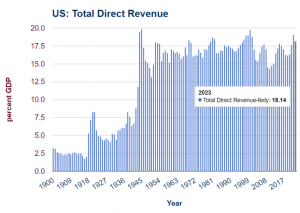

The inevitable conclusion of this budget commission charade will be that Congress has to raise taxes. But that will not work, because raising tax rates does not raise the federal government’s revenues above 17.4 percent of GDP for long, if at all. Here’s a graph I’ve used before to illustrate the point:

Notice that the graph lists revenue for 2023 at 18.14 percent? Federal tax revenue started falling almost immediately after I posted that item in February of this year: “Uncle Sam’s tax collections were down 26% in April compared to last year at the same time, according to new estimates Monday by the Congressional Budget Office that offer a worrying picture about the state of government finances,” The Washington Times reported in May.

Notice that the graph lists revenue for 2023 at 18.14 percent? Federal tax revenue started falling almost immediately after I posted that item in February of this year: “Uncle Sam’s tax collections were down 26% in April compared to last year at the same time, according to new estimates Monday by the Congressional Budget Office that offer a worrying picture about the state of government finances,” The Washington Times reported in May.

Sometimes it positively hurts to be so right.

Federal spending can go as high as the fantasists in Congress want it to go, but revenue is a stubborn thing.

Spending was at 23.15 percent of GDP in the third quarter of this year. That is 5.75 percent of GDP more in spending than the government can hope to raise in revenues.

I can save the commission a lot of time. Cut spending by 5.75 percent of GDP. Problem solved.

The only way to increase federal revenue sustainably is to raise the tax base. The only way to raise the nation’s tax base is through economic growth. A growing economy increases the size of the pie from which you get your 17.4 percent in taxes.

The only means the federal government has for spurring real economic growth are tax cuts and reductions of regulation. Cutting tax rates and reducing regulation will increase tax revenues over time. It always works. (What creates the inevitable subsequent budget deficits are new spending increases that always seem to follow tax cuts the way wolves follow deer.)

It is crucial to cut spending until the greater tax revenues arrive. Otherwise, you end up in an even worse debt spiral as the government increases tax rates repeatedly in a hopeless dream of trying to pry more tax revenue out of the public.

OK, so listen up, Congress. Cut taxes, and cut spending. Then you will get more money, and you can spend more—later, after the money comes in. For now, you’ve got to bite the bullet and stop spending so much.

You may send me the payment for my advice care of The Heartland Institute.

Source: The Center Square

What Is Income?

The U.S. Supreme Court heard arguments last week on one of the most important tax cases to arise in many years.

The question before the Court is whether Congress may rightly tax increases in the value of things people own, even if the owner is merely holding the property and does not realize any payment from anyone for the use of it, as through sale, rental, or the like.

Writing at The Wall Street Journal, Richard Rubin and Jess Bravin describe the issue in Moore v. United States as follows:

The case, brought by a Washington state couple seeking a $14,729 refund, raises a seemingly simple question: Must income be “realized,” or received, before it can be taxed?

Charles and Kathleen Moore argue that when the law passed, they hadn’t realized income from their investment in an India-based company and thus couldn’t be taxed. Some conservative groups have backed them, seeing a chance to block future Congresses from taxing wealth or unrealized capital gains. A broad ruling for the Moores could create a constitutional bar against some popular Democratic proposals to tax the super-rich.

The problem, as the Journal writers see it, is that there are numerous forms of income the federal government taxes that are not directly received by the individuals as payments. The writers provide several examples.

Those taxes, they note, will be subject to challenge if the Court rules “too broadly” in requiring income be clearly realized in the form of a payment before Congress may tax it.

That’s an interesting point, yet it is not anything that should enter into the Court’s consideration. Retaining an unconstitutional principle because the Congress has relied on it for decades is not a justifiable position. If something is unconstitutional, the Court should not uphold it. To do so is to violate the rule of law. Continuation of multiple wrongs does not make a right.

The Journal is correct to note that this case is all about definitions. The Sixteenth Amendment, which establishes the constitutionality of a federal income tax while otherwise retaining the Constitution’s ban on direct taxes not apportioned among the states according to population (Article I, Section 9, Clause 4), is of course the relevant item here: “The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes on incomes, from whatever source derived, without apportionment among the several States, and without regard to any census or enumeration.”

Obviously, the definition of the term income is central to this issue. There are other critically important terms that come into play when we consider the meaning of income, however, and the Court ought to look at these carefully as well, and define them honestly. Those definitions should reflect the meanings those words had in 1909 and 1913, when the amendment was passed by Congress and ratified by the states, respectively.

Here are some thoughts to get them started. We generally think of income as additional wealth coming to a person or other entity. That’s simple and reasonable. Income constitutes an increase in one’s wealth.

That does not mean, however, that every increase in wealth is income, especially when considered in practical terms. Every human being is a mammal, but not every mammal is a human being. Just so, every instance of income is an increase in wealth, but not every increase in wealth is necessarily an instance of income.

The question is this: Is an increase in the value of something you own income? Always?

The obvious answer is no. We own plenty of things, and sometimes they increase in value while in our possession, yet in nearly all cases we receive no benefit from that. If you have a gold wedding ring and the price of gold rises, your wealth has increased. But all you have is the same old wedding ring, dear as it may be to you. Clearly, you have not received any income through this passive increase in your “wealth.”

If you sell the ring, however, at a price higher than what you paid for it, you do receive a net increase in your wealth. That is income, in the constitutional sense (though economically it is exchanging currency for money, i.e., gold).

The same is true of your domicile. If your house increases in value and you still live there, you do not receive any income. All you have is the same old house. From your perspective, the increase in value is purely potential until you try to sell it.

The Moores owned a relatively large share of a foreign company. The value of the company increased. All the Moores had, however, was the same old shares of the company. They might be able to get a bigger bank loan at a lower rate with those shares as collateral—but they did not even do that, as far as I can discern. They just continued owning the shares.

The Journal is right to note that many provisions in the nation’s tax code will be invalidated if the Supreme Court establishes that Congress may not tax unrealized increases in the value of people’s property. That does not make it right. The nation’s tax code is a repulsive mess anyway. Forcing Congress to reform it does not strike me as an atrocity.

Nonetheless, the Justices do appear to be worried about the potential consequences of their upcoming decision, the Journal notes in another article by the same two writers:

But several justices seemed less concerned with hypothetical future taxes than with possible effects on statutes long familiar to investors, tax advisers and businesses. Those include the Internal Revenue Code provision known as Subpart F, which since 1962 has required many American shareholders in foreign corporations to pay taxes on their pro rata portions of those companies’ undistributed passive income. It prevents Americans from placing assets inside foreign corporations as a way of deferring U.S. taxes.

The judges spent a good deal of their oral argument time in the mud-wrestling pit that is tax policy, with Trump appointees taking opposing positions based on their views of the potential consequences of a decision on the definition of income for tax purposes:

Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar, defending the Trump-era tax law, told the court that the 16th Amendment imposed no realization requirement on taxing income, but even if it did, the Moores’ investment would fall under it.

Justice Neil Gorsuch found that argument troubling, saying the government’s argument opened the door to taxing “millions of Americans who hold small amounts of stock in their retirement investment accounts.”

Prelogar said while Congress had that power, it has never sought to impose such taxes and such far-fetched hypotheticals were a distraction from the narrow question before the court.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh agreed. “Members of Congress want to get re-elected,” he said. “That’s why they are far-fetched.”

Such matters are none of the Justices’ business, if I may be so bold as to point that out. Their job in these cases (if you believe in judicial review) is to ensure that the Legislative and Executive branches and lower courts operate under the strictures of the nation’s Constitution. That is enough for any nine people to take on. Deciding what the nation’s tax code should look like is the job of Congress. It is the Court’s job to make sure only that Congress is operating within its authority.

The task before the Supreme Court is clear: one, properly define income, and two, require the government to prove that something is income before Congress may tax it. Then, stop.

Sources: The Wall Street Journal; Moore v. United States; The Wall Street Journal

The Fed’s Unemployment Fetish

Regular readers of this newsletter will be familiar with my disdain for the Federal Reserve (Fed) governors’ belief that unemployment is good and an abundance of jobs is bad. (See also issues here, here, and here, just for starters.)

It was, therefore, a great pleasure to see one of my favorite economists and writers, George Gilder, take up this same argument recently. Writing for his Guideposts newsletter, Gilder and cowriter Richard Vigilante note that “one of the Fed’s most cherished and wicked beliefs” is “that what America needs is more citizens without work.”

The Fed’s premise is that good news for workers is bad news for … whom, exactly? “The economy,” it seems, the idea being that an abundance of jobs means that workers will bid up the cost of labor, which employers will have to cover by raising their prices, which will constitute price inflation.

Two weeks ago, Gilder and Vigilante note, the press and the markets, led by the Fed, reacted with glee to the news that the economy added fewer jobs than expected last month:

Deafening was the hallelujah chorus at this week’s news that job openings have gotten scarce. Only a few months ago, according to the Department of Labor, the American economy was a Surf City of opportunity with two jobs for every boy (or girl). Dangerous! we were told. Could lead to Americans getting raises, which would “fuel inflation” or even “institutionalize” a “wage-price spiral” from which there would be no safe escape.

Now, however, all is well. The ratio of available workers to jobs has come down to about 1 to 1.3. Mirabile dictu, some job seekers will stay unemployed and poor! Even better, fewer workers will find an upside surprise in their pay envelopes.

The employment news brought great joy to the markets because it means the Fed will not further tighten the money supply to stave off inflation, which has already been defeated but is always threatening to return. Inflation, you will recall, rose rapidly in the wake of the post-pandemic stimulus (meaning: overspending) by the Biden administration and Congress beginning in 2021, aggravated by the pandemic-era supply chain disruptions which suppressed the production of goods and services, which happens to be what people generally spend their money on. More money chasing fewer goods and services fueled inflation.

Producing more goods and services would, therefore, help solve the inflation problem, and it has done exactly that. In addition, the Fed has been rapidly tightening the money supply. Inflation cannot “come roaring back” when the money supply is decreasing, unless the production of goods and services crashes. (Biden is doing his best to cause that, to be sure.) Therefore, we should welcome this greater economic production and the jobs that it creates and in fact requires.

The Fed, however, does not like rapid job growth, and the conventional wisdom follows the Fed’s lead, even though it is obvious hogwash:

How can anyone believe that more people, doing more work, and producing more goods and services is “inflationary?” Even accepting the dismal visions of orthodox economics, hopelessly bound in myths of equilibrating supply and demand, shouldn’t additional supply reduce prices? Haven’t we just been making our way out of a period when prices soared precisely because the massive forced shut down of national economies wreaked havoc on supply chains?

It did really seem, for a moment, that even the government had been about to admit that pandemic prices rose largely because the supply of goods fell. Even some Fed folk recently were heard saying right out loud that refilling supply channels was the way to cut prices. Yet now they are back at it with the notion that more productivity will [make] us poor.

Economic expansion is not inflationary, Gilder and Vigilante note, because the production of goods and services will increase by more than the workers’ wages will rise, meaning productivity has gone up. Employers cannot pay workers more than the latter increase the production of goods and services (not for any appreciable period of time, anyway, and certainly not across the entire economy); I would add, unless the central bank expands the money supply excessively.

Therefore, as more workers do more work all across the country, there is more for them and others to spend their money on, and thus expansion of production does not create inflation:

Yes, more workers working and getting paid more means they will have more money to spend. Even by the standards of orthodox economics, this could drive prices upward only if the workers are paid more than they are worth. As long as workers on average produce value greater than or equal to what they are paid, their increased earnings cannot be “inflationary,” even in the sense of boosting what the orthodox call “aggregate demand” over supply.

Gilder and Vigilante usefully point out that having a central bank manipulate the money supply to keep prices stable is in fact intrinsically destructive and unnecessary. It is destructive because it sends false signals across the entire economy:

As our friend John Tamny reminds us, “inflation” is meaningless unless it means a devaluation of a currency against some reliable standard. Prices shifting up and down across economic sectors are not inflation but useful signals to producers and consumers to adjust their behavior opportunistically.

Note, by the way, that the “opportunistic” changes in economic behavior to which Gilder and Vigilante allude are how people deliver resources to their most-valued uses. Manipulation of the money supply creates widespread misinformation that causes economy-wide misallocation of resources. If only the Biden administration were willing to fight that type of misinformation instead of the embarrassing truths they regularly try to censor, we’d all be much better off.

Manipulating the money supply is also unnecessary, the writers note, because there’s a very simple and reliable way to keep a currency as stable as possible:

Even to measure inflation accurately, much less control it, we need [a] reliable standard, the most reliable being gold.

The world’s gold stock has increased relentlessly at 2% annually for centuries. (Even as mining technology improves, the gold still in the earth becomes harder to reach). That phenomenon, besides piling on the evidence for a providential God, makes gold the perfect money.

I’ll add that our nation’s persistent money problems began and prices became more volatile in 1971 when President Richard Nixon ended the convertibility of the U.S. dollar to gold:

Source: St. Louis Fed

In addition to pegging the currency to a stable item such as gold, I would note that the key to stopping inflation is to keep federal government spending and regulation under control. Government spending redirects money and resources from their most economically productive uses to less-productive ones; we do that because we think the less-productive uses are more valuable in some way other than in purely economic terms. But they have a cost. Regulation costs us too, by reducing the production of goods and services (see item 4 in the hyperlinked article), and significantly: it’s costing the American people the equivalent of almost $2 trillion per year at present.

Gilder and Vigilante recognize the economy is all about the production of goods and services, and the best way to fight inflation is to unleash the hard work and ingenuity of human beings for that purpose:

As long as a gold standard is politically impossible, the only reliable enemy of inflation is a robust, free economy in which money keeps its value because there is always something useful to do with it. Destroying jobs won’t get us there.

Inflation is everywhere and always a failure of government. The Fed’s habit of destroying people’s livelihoods is indeed wicked, as Gilder and Vigilante note. It is also stupid.

Source: Gilder’s Guideposts (to subscribe)

Cartoon